You’re on the go and nature calls — where to go to go? That is the question. More than a century ago a newspaper article observed, in all “American cities, practically no provision is made for ‘public comfort stations’ outside of saloons. Department stores provide these ‘for customers only.’ Hotels provide them ‘for guests only.’ A stylishly dressed man can bluff his way into a hotel, but a common man, a workingman, a teamster, for instance, or a brickmason, let him venture into a hotel toilet-room if he dares.” Sadly, not much has changed. Today, if you are driving out and about, there is always the friendly filling station, or maybe a fast-food establishment, or a shopping mall or a mega store to find relief. However, if you are in a downtown area, finding a restroom can be as challenging as it was in earlier times. Many stores post signs reading “No Public Restroom,” and you need to run the gauntlet of metal detectors to enter public buildings. Most likely, you have to search out a coffee shop, stand in line to buy a cappuccino or latte (as if that is what you need at this time), and ask for the code to the restroom. Homeless people face even more arduous challenges to simply relieve themselves.

The idea of public comfort stations goes back to ancient Rome where public toilets were in common use for men. Long lines of benches with holes accommodated multiple users at the same time. Privacy was not a consideration; the use of these public latrines was considered a male social activity. Over the following centuries, public facilities became uncommon and it wasn’t until the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London that public toilets reappeared with separate compartments for men and women. Other large European cities soon followed in installing modern public toilets for both sexes during the Victorian Era. In 1897 an Indianapolis city councilor proposed that the board of works “rent two rooms on Washington St, between Capitol Av and Delaware St, to be fitted up as a public toilet room.”

In 1906, Mayor Bookwalter began urging the city council to appropriate funds for a comfort station in the downtown business district, noting, “At present the only conveniences for women downtown are the department stores and for men the saloons and hotels.” Finally, in the fall of 1909, in the waning days of the Bookwalter administration, the council appropriated $20,000 (2022: $668,417) for the construction of Public Comfort Station No. 1 in the middle of Kentucky Ave., partially under the pavement, at its intersection with Illinois St. However, it was not until January 1910 and the new administration of Mayor Shank that William F. Stillwell of Lafayette was awarded the contract for the construction of the facility.

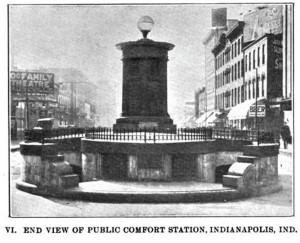

Architects Herbert W. Foltz and Wilson B. Parker drew up plans for the comfort station containing two rooms, one for men and one for women. While most of the stalls were free for public use, a few stalls had “numerous extra conveniences, such as a clean towel, a fresh cake of soap, a washbowl, comb and clothes brush” available by depositing a nickel in a slot. The station was ventilated by a large suction fan “which forces the foul air out through a ventilator in the tower.” The comfort station opened on July 18,1910 with about 2,000 persons inspecting the facility between noon and 11 p.m. Afterwards, the regular open hours to the public were from 7:30 a.m. to 11:30 p.m.

The first comfort station attendants appointed by the board of public works were Margaret Dollarhide, matron, along with Levonia Scervones and Clara J. Hart, janitors. John Pence was named head janitor along with William Loveless and George Dingry, janitors. The salary of the attendants was a rare example of “equal pay for equal work;” the matron and head janitor were each paid $50 (2022: $1,611) per month and the women and men janitors were each paid $40 (2022: $1,289) per month.

Indianapolis Comfort Station No. 1 was the subject of an article in the December 1910 issue of Municipal Engineering that compared it with the public comfort station in Brookline, Massachusetts. The design of the Indianapolis facility was criticized because it was “neither of the above ground nor under ground type, but seemed to be a combination of the two,” while the Brookline facility was “given as an example of the proper construction for an underground type of station.” One observation was that the Indianapolis station was “all buried but the ventilating tower and it was left to stand out like a sore thumb.” This unfavorable article may have led, in part, to a remodeling of Comfort Station No. 1 six years later. When it was remodeled in 1916, the entrances to the facility were relocated to the sidewalks on either side of Kentucky Ave. instead of in the middle of the street and the roof was made flush with the surface of the street.

In the early twenties, police powers were given to the attendants after complaints that the comfort station was “little more than a place…bootleggers ply their trade on the men’s side and street walkers change their clothes and ‘doll up’ on the women’s side.” By 1960, the comfort station had become a “dingy spot,” visited by “hardly anyone but an occasional derelict.” After a campaign by city councilor Tom Hasbrook to eliminate funding for the comfort station attendants, the board of public works instructed the city street commissioner in October 1963 to seal off the underground restrooms with slabs of concrete. Today, the site lies beneath Merchants Plaza (PNC Center).

After an absence of almost sixty years, a public restroom was recently opened by the Indianapolis Office of Public Health & Safety in the downtown area. The facility, located next to the old city hall building, 202 N. Alabama St., is a shipping container, painted blue, and adapted for the purpose containing two stalls.

-

Other News This Week

- Glasses On, Glasses Off

- Just a Little Motion Can Dramatically Improve Your Health

- Franciscan Health Hosts ASIST Suicide Intervention Course May 10-11

- Coburn Place Launches Campaign for Housing for Domestic Violence Survivors

- State of Indiana Launches SUN Bucks

- Primary Voting 2024 on May 7

- This Week’s Issue: May 3-9

- “Full Court Press” Episode 1 Special Screening at Newfield

- 100 Years Ago: May 3-9

- 2024 Summer Reading Registration Begins May 1

Search Site for Articles