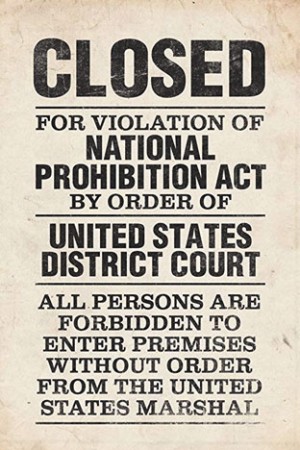

John Barleycorn died at midnight, January 16, 1920. Hours earlier, a group of about seventy-five Indianapolis “Drys” had gathered at Central Christian Church in celebration of the anticipated event. Yes, the 18th Amendment to the United States Constitution had gone into effect, and prohibition, the great “noble experiment,” embraced the country.

However, little changed in Indiana; the Hoosier State had been Dry since the stroke of midnight, April 2, 1918. The 3,520 bars in the state, including 547 bars in Indianapolis, had sold their stock and closed, although a few clung to life for a short time as “dry beer” places selling soft drinks. Some of the 15 distilleries in the state continued to make alcohol for the federal government and a handful of the state’s 35 breweries turned to the manufacture of soft drinks. “Sparkling, invigorating, thirst-defying” cereal beverages like Tonica, a near-beer made by the Indianapolis Brewing Co, became “America’s Ideal Beverage.” Druggists took out permits to receive shipments of grain alcohol and to sell intoxicating liquor for “medicinal, mechanical and sacramental purposes.”

The country would adjust to national prohibition as Hoosiers adjusted to state prohibition. Since there was no law against home brews, adherents to “Old John Barleycorn” experimented with homemade concoctions, making some strange and fancy substitutes for the real stuff. Home-brewed beer made from a so-called extract of malt and hops, a little yeast, and boiling water produced a “pleasant beer scarcely distinguished from old-time brewery products.” Adding a few raisins to a bottle of near-beer and letting it stand for twelve hours gave the beverage a “zip,” and a little Jamaica ginger in a glass of “dry beer” produced the “desired effect.” Sweet cider put through a cream separator resulted in something unusual known as “Indiana Lightning,” and a concoction of prunes, oatmeal, and water made Hessian Rum. In search for more kick, former beer drinkers often resorted to all sorts of formulas and recipes in making home brews including some that “could be ruinous to the stomach.”

For those who had a thirst for the real stuff, bootlegged whisky and gin kept the purveyors of prohibited drink, known as blind tigers, throughout Indianapolis well supplied. By the end of 1918 the city police had made 700 arrests for bootlegging and operating blind tigers. Transporting glass liquor bottles had its risk. Two smugglers, who were traveling on a Pennsylvania passenger train from Columbus, Ohio to Indianapolis, were discovered as the train approached Irvington when some of the bottles that they were carrying in two suitcases broke and the odor of whisky wafted through the car, attracting the attention of the conductor. The smugglers jumped the train; the suitcases containing 157 half-pints of whisky were turned over to the police when the train reached Union Station.

Illegal stills of all sizes operated across the city from the onset of prohibition, and clinking sounds of glass could often be heard at night emanating from garages and barns. In the early years of enforcement, the largest and best equipped still confiscated, with a 300-gallon capacity, was found in a barn in the Irvington area back of a “fine looking house” at Fletcher and Emerson Avenues. Later, a fifty-gallon still, making “white mule” testing 175 proof, was found in an Irvington dry cleaning establishment at Washington St. and Bolton Ave. On the city’s west side in Haughville, undertaker Charles Stevens was arrested for “engaging in the manufacture of ‘white mule’ as a sideline.” He delivered his product from his two twenty-gallon stills at night in his “dead wagon.” Also, the southwest side’s Fleming Garden neighborhood was “a regular bootlegging community” known as “the Little City of a Thousand Stills” where distillers “have a practice of borrowing each other’s stills, making it unnecessary to go to the expense of buying or having one made.” It was said that when the three Indianapolis breweries closed, 3,000 private stills opened.

Hardly a day passed in Indianapolis without multiple arrests of persons on blind tiger charges. Possession of a half-pint of whisky or moonshine could result in a stiff fine of $50 (2018: $759) in city court; more severe violations of the prohibition law brought a hefty fine of $200 (2018: $3,037) and sixty days at the State Farm. In response to the flagrant bootlegging, the Indiana Anti-Saloon League secured new state laws in 1923 imposing mandatory fines and sentences for “second and subsequent offenses.” Transporting any amount of intoxicating liquor became a felony punishable by one to two years in the State Prison and a fine up to $1,000 (2018: $14,918); owning a still was a felony punishable with up to five years in State Prison and a comparable fine. Despite the heavy penalties and with a state Supreme Court decision that “mere possession of intoxicating liquor” was not a crime, white mule became so plentiful in Indianapolis that the price dropped from $12 (2018: $179) to $5 (2018: $75) a gallon.

The personal and economic toll of Prohibition can be seen in Indiana’s experience. With the closure of bars, breweries and distilleries, 9,500 people were forced to seek other occupations. While the Indianapolis Brewing Co. continued to make a legal product, the workforce went from 1,000 employees to 15. The estimated $25,000,000 (2018: $422,683,412) spent annually for liquor — money that went for wages, purchasing goods and services, and taxes — was now gone from the state’s economy. In Indianapolis, the loss of revenue from liquor licenses caused a 20 percent increase in property taxes.

During the period of federal Prohibition, more than 6,500 Hoosiers were arrested on federal liquor violations with more than 4,300 either pleading guilty or being convicted; approximately $800,000 (2018: $15,697,863) in fines and forfeitures were collected. In Indianapolis, 23,250 citizens were arrested for operating blind tigers or stills, and almost $400,000 (2018: $7,848,932) in fines were levied in city court for violations of state liquor laws. Local kingpin Tony Ferracane was the center of “the largest and most far-reaching liquor conspiracy” of the Prohibition era in Indiana, distributing 1,500 gallons of liquor a week between Indianapolis, Louisville, and Chicago. He was convicted along with 99 other persons and served eighteen months at the Ft. Leavenworth (KS) federal penitentiary.