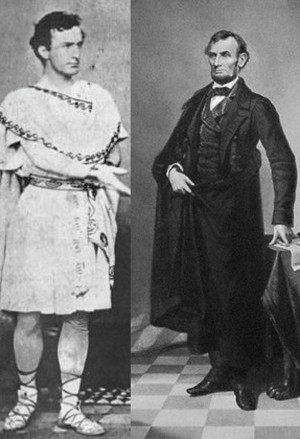

One hundred and fifty years ago, an ominous event took place that must surely ranks among the most unusual portentous footnotes in all of American history. On November 9, 1863, just nine days before he boarded a train bound for Gettysburg enroute to deliver the most famous speech in American history, President Abraham Lincoln and his wife Mary attended a play at Ford’s Theatre by Charles Selby called The Marble Heart (also known as “The Sculptor’s Dream”). The play tells the story of a Greek sculptor, reincarnated as a Frenchman, whose marble sculptures eventually come to life right before his eyes. The lead character, Raphael Duchatlet, is the greatest sculptor in 19th century Europe. The actor playing Raphael for the President this night was a 24-year-old heartthrob named John Wilkes Booth. Seventeen months later, this duo would meet again in the same place with disastrous results.

Ironically, Ford’s Theatre began life in 1833 as the First Baptist Church of Washington, D.C. The congregation merged with the Fourth Baptist Church and moved to larger quarters in 1859. The building sat abandoned and empty for the next two years before theatre manager John T. Ford obtained a five year lease on the building. In 1862, Ford spent $10,000 ($233,000 in today’s money) renovating the building before opening it as Ford’s Athenaeum. On December 30 of that year, the building’s exterior was destroyed by fire. Although no one was hurt, the damages totaled over $20,000.

In 1863, he reopened the 1,500-seat venue under the name Ford’s New Theatre and it quickly became the hottest spot in town to see a stage production. Over the next two years, Abraham Lincoln visited the theatre eight times. The first of those visits was to see the hottest young actor in the country, John Wilkes Booth, in The Marble Heart. Booth, one of Ford’s closest friends, was among the first leading men to appear in the newly minted theatre. The Marble Heart marked Booth’s first appearance at Ford’s Theatre.

Lincoln was a voracious reader of Greek classics who considered William Shakespeare his favorite author. He enjoyed going to the theater, where he could spend a couple of hours uninterrupted by the constant call of visitors and the troublesome news arriving almost constantly from the front lines of the Civil War. The theater was one of the few places Lincoln could relax. Newspaper editor John W. Forney remarked on Lincoln’s behavior while watching a play: “Mr. Lincoln liked the theatre not so much for itself as because of the rest it afforded him. I have seen him more than once looking at a play without seeming to know what was going on before him. Abstracted and silent, scene after scene would pass and nothing roused him until some broad joke or curious antic disturbed his equanimity.”

One frequent theater companion of the President was Indiana Congressman, Speaker of the House, and Vice-President under Ulysses S. Grant, Schuyler Colfax. He recalled about visiting Ford’s Theater with the President: “We used the theatre to regale ourselves of an evening, for we felt the strain on mind and body was often intolerable.”

President-elect Lincoln saw Booth perform in New York City and it can be easily assumed that Mr. Lincoln was looking forward to seeing him perform again. What Lincoln could never have imagined was that since that first encounter back in 1861, this rising young star he knew as Booth had by now formed an obsessive contempt for the President. By the next time Lincoln saw the young actor at Ford’s Theatre on Nov. 9, 1863, Booth was moonlighting as a spy and courier for the Confederacy and was driven by a seething hatred of Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln watched the play that night from the box directly below that which would be the site of his doom a year-and-a-half later. One of the guests of the Lincoln’s that evening was Mary Clay, daughter of Cassius Clay, the U.S. minister to Russia. Years later, she reminisced about that night: “In the theater President and Mrs. Lincoln, Miss Sallie Clay and I, Mr. Nicolay and Mr. Hay (Lincoln’s young private secretaries), occupied the same box which the year after saw Mr. Lincoln slain by Booth (It was actually the box below the death box). I do not recall the play, but Wilkes Booth played the part of villain. The box was right on the stage, with a railing around it. Mr. Lincoln sat next to the rail, I next to Mrs. Lincoln, Miss Sallie Clay and the other gentlemen farther around. Twice Booth in uttering disagreeable threats in the play came very near and put his finger close to Mr. Lincoln’s face; when he came a third time I was impressed by it, and said, ‘Mr. Lincoln, he looks as if he meant that for you.’ ‘Well,’ he said, ‘he does look pretty sharp at me, doesn’t he?’ At the same theater, the next April, Wilkes Booth shot our dear President. Mr. Lincoln looked to me the personification of honesty, and when animated was much better looking than his pictures represent him.” Mary Clay, in her reminiscence, was off by a year when she said the president was shot “the next April.”

Another guest that night, a secretary of Lincoln’s, described Booth’s acting as “more tame than otherwise.” This witness recalled that Mr. Lincoln “rapturously” applauded Booth’s performance. After the play, Lincoln sent a note backstage inviting Booth to come meet him at the White House. Booth evaded the president’s invitation, never giving Lincoln a specific reason why he could not visit. Upon hearing of Lincoln’s appreciation of his acting skills, Booth, one of the most vehement racists of his era, remarked to friends ‘I would rather have the applause of a Negro to that of the president!’”

On another occasion when Lincoln’s son Tad saw Booth perform, he said the actor “thrilled him,” prompting Booth to give the President’s youngest son a rose. However, Booth ignored an invitation to visit Lincoln between acts. On February 10, 1865, at another Ford’s Theatre performance just weeks before the assassination, President Lincoln attended the play Love or Livery. Although Booth was not in this play, it did star John Sleeper Clarke — John Wilkes Booth’s brother-in-law. Lincoln had two guests with him that night who would play a part in the tragedy two months later; Generals U.S. Grant and Hoosier-born Ambrose Burnside. General Grant was supposed to have attended the play Our American Cousin with Lincoln that night but backed out at the last minute. General Burnside did attend the play. Some historians contend that it was the sight of Burnside that caught Lincoln’s attention, causing the President to look down and to the left from the elevated box onto the main floor seating area at the exact moment Booth fired his weapon. This movement would cause the bullet to come to rest behind Mr. Lincoln’s left eye.

Long afterward, another actor recalled how Lincoln admired Booth by saying, “I know that, for (Lincoln) said to me one day that there was a young actor over in Ford’s Theatre whom he desired to meet, but that the actor had on one pretext or another avoided any invitations to visit the White House.” Isn’t that exactly what you might expect of Abraham Lincoln? A man whose gentle soul was so full of grace, goodness and dignity; oblivious to the murderous hatred boiling inside the young actor. After all it was Lincoln who once famously said, “Do I not destroy my enemies when I make them my friends?”

The kind hearted Lincoln could never have imagined that this, the youngest of the famous Booth family of actors whose work he so admired, was destined to become America’s first presidential assassin. And that he would be the first martyred murdered magistrate in our country’s history. What’s more, no one could have dreamed that the play’s title, The Marble Heart, could serve as such an appropriate metaphor for the dastardly tunic-garbed coward trodding the boards of the old church before the most beloved man in American history. John Wilkes Booth’s heart could be likened to marble: hardened by rage and fury, streaked with misguided political outrage, stone cold with bigotry and polished with egomaniacal madness. After all, only a marble heart could be capable of the murder of Abraham Lincoln.

Al Hunter is the author of “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Indiana National Road” and “Haunted Irvington” book series. Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.