This article appeared in the August 24, 2018 issue and did not post to the Web site due to a technical error. Apologies to our “Bumps in the Night” and Al Hunter fans!

I speak often about America’s first serial killer, the evil Dr. H.H.Holmes, and his demonic doings in 1894 Irvington — including his habit of selling the cadavers of his victims to Chicago area universities for $75 each. Today, these stories elicit gasps and disbelief from all who hear them. However, there was a time when grave robbing in our capital city was a very real threat indeed.

The act of grave robbing was so common that perpetrators began to see themselves as businessmen providing a much needed service rather than the night creeping, gutter crawling slags of humanity that they truly were. Often these ghouls ruled the nightlife scene, holding court in local bars and taverns while regaling customers with their tales from the boneyards of our dear city, with no real fear of retribution, much less prosecution, for their dastardly deeds. After all, their skill and services were in demand by uber-educated medical school professors, upper-crust physicians and high-bred college students from all four corners of the city, no questions asked.

In January 1875, a reporter for the Indianapolis Herald newspaper interviewed one such ghoul for an article on grave robbing titled, “How the Business is Managed at Indianapolis. Twelve ‘Resurrectionists’ engaged in it.” Sadly, the name of the intrepid reporter is lost to history, but his words live on and are offered here as proof that this gruesome occupation did in fact exist. Here is the article as it appeared almost a century-and-a-half ago:

A reporter for the Indianapolis Herald recently fell in with a resurrectionist, or body snatcher, who relates the following story: “Yes, I know it’s a shameful business. But I have no longer any capacity for shame. This (holding up his glass) has done the business for me. It has made me what you see me. Once I was a reputable physician with a diploma from ——– College, and a fair practice, and now I am a body snatcher, sneaking through the graveyards by night, and spending the proceeds of grave robbery in low down thief kennels by day. You don’t often see me here. Hunger-hunger for whiskey brought me here tonight, because I am more apt to sponge a drink or two among such tipplers as you than I would be among ruffians of my own sort. As I said, I have no shame, but I know how low it is. I know that a man capable of grave robbing for gain is cutthroat enough at heart to do murder if he were not too cowardly. Why don’t I reform? That’s a good joke. I look like it don’t I? I tell you it’s impossible. There’s no retreat for me. The only road open to me is in front, and it ends in hell. Another drink . . . and a big one, to settle these grinning devils that have been dancing around me all night, and I will tell you all about the business. As the season is over and Dr.——– has promised to buy me a ticket to Memphis, I don’t care.”

HOW STIFFS ARE RAISED: “A ressurectionist’s kit is not very expensive, sir. All he needs is a rope with a hook at one end, a short crowbar, and a spade and a pick. He generally has a “pard,” as it is easier to hunt in couples. He is notified of the “plant” (body), and by personal inspection makes himself familiar with all the surroundings, before the attempt is made. The pick and spade remove the earth from the grave as far as the widest part of the coffin, and with the crowbar, the coffin is shattered, and the rope with the hook end fastened around the cadaver’s neck, when it is drawn out through the hole without disturbing the earth elsewhere. As soon as the cadaver is sacked, the earth replaced, and the grave made to look as near like it was as possible. There are some bunglers however, who have been guilty of leaving the grave open, with fragments of the cadaver’s clothing lying around. They are a disgrace to the profession, and have done much to foster an unfriendly public sentiment in this city.”

HOW A SALE IS NEGOTIATED: “No, there’s not as much difficulty in negotiating the sale of a stiff as you would imagine. The resurrectionist has no dealings with any member of the colleges. They are too smart for that. The janitor does the business. A wagon with two men in it drives up in front of a college. Maybe the streets are full of people . . . maybe not. It makes no difference any way. The wagon barely stops a moment, and one man shoulders the sack containing the stiff and shoots into the college basement, and the wagon drives off. Police? (The resurrectionist here shook like a mass of jelly with inward chuckles.) Why, bless your simple soul, there is no more danger of being interrupted by the police than there is of me dying a sober man. The police on the college beats are friendly to science. They wouldn’t, for two dollars a stiff, make a row about it, you bet. So all the digger has to do is put a mask on his face and slip in to see the janitor, who is provided with funds, and shells out without being too particular about identification.”

THE NUMBER OF RESURRECTIONIST: “There are at least a dozen diggers engaged in anticipating the tooting of Gabriel’s horn in this city. Some of them are working for other cities. There is Mr. ——-, a tall man, with long, dark hair, seedy clothes, and a sinister expression of countenance. He’s a man of education, and has respectable connections in the city. What brought him to it? What brings us all to it? Whiskey, of course. He works with Mr. ——-, a lanky, long haired fellow, with rebel looking clothes, and long, light, lousy looking hair, mustache, and goatee. Yes, it was him that was kicked out of the boarding house for talking “stiff” at the table. Then there is the brother of a well-known doctor, and a doctor out in the country, and others too tedious to mention. Some of the students, too, raise their own stiffs as a matter of economics. Material is getting costlier every year.”

THE MOST FRUITFUL FIELDS: “The most of the stiffs are raised at Greenlawn cemetery (in Franklin, south of the city), at the Mt. Jackson cemetery (on the grounds of Central State hospital), and at the Poor Farm cemetery (Northwest of the city). So far as I know Crown Hill has never been troubled. Many of the village cemeteries in the neighboring counties are also visited, however, and made to contribute their quota to the cause of science. Some of these village cadavers are those of people who moved in the best society, and besides their value in material for dissection, are rich in jewelry, laces, velvets, etc. The hair of a female subject is alone worth $25. Nothing is wasted, you may be sure. Even the ornaments on the coffin lids are used again..”

SMART ALECKS: “There is a good joke on the Marion County Commissioners. You may remember that, on account of so many complaints against body snatchers, these Smart Alecks had a vault built, in which to deposit bodies, and put a padlock on the door. You may believe the resurrectionist didn’t stop long for a common padlock. It didn’t take long to get an impression with a piece of wax, and any darn fool can make a key that will unlock a padlock. And the vault business saves a heap of hard digging. Many a stiff has been cut up in our colleges without having been buried at all. I know of one case where it came pretty near making a rumpus, and there was lively skirmishing for a time, I tell you.”

FURTHUR (sic) PROSPECTS: “Allred? Him? Why he could not stop a worm. He is devoted to science, and if he wasn’t, all we’d have to do would be to get him a bottle of Rolling Mill rot gut, and he would neither see nor hear. Do you s’pose that there could have been so much resurrection in Greenlawn, right in the heart of the city almost, if somebody hadn’t been fixed? I don’t know. Do you?” (Allred was apparently the superindendent of Greenlawn cemetery)

A MEAN TRICK: “Now I’m goin’ to tell you about what I call a mean trick. A stiff had been raised out of grounds supposed to be the peculiar property of one of the colleges, and sold to another. It wasn’t much of a stiff, a poor, miserable, emaciated Negro, that didn’t weigh more’n ninety pounds . . . but it made the faculty of ——– college madder’n hornets to think that a stiff out of their ground had been sold to a rival college. You know they hate each other like pizen anyhow. Well, Tuesday night of this week they broke into the college vault and stole the stiff, and the next day a Professor of the rival college lectured over it. Go to the law about it? Not much. They know how to leave well enough alone. But they were not about it, you better believe. Goin’, are you? Well, good night. The chances are that we’ll never meet again, an there’s nothing doing here, and I want to get to a warmer climate. Good night, Sir.”

The night was a grave robber’s best friend. He lived in it, worked in it, played in it, and hid in it. Late at night, these ghouls would steal into cemeteries where a burial had just taken place. In general, fresh graves were best, since the earth had not yet settled and digging was easy work. Laying a sheet or tarp beside the grave, the dirt was shoveled on top of it so the nearby grounds were undisturbed. Most body snatchers could remove the body in less time than it took most people to saddle a horse. They would carefully cover the telltale hole with dirt again, making sure the grave looked the same as it had before they came. They’d take the body away via the alleyways and sewers of the city, finally delivering the anonymous dearly departed to the back door of a medical school. In time, several of these ghouls began to furnish fresh corpses for sale by murdering the poor, homeless citizens of the city who once stood silent vigil in the alleys as the grave robbers crept past with their macabre cargo in tow.

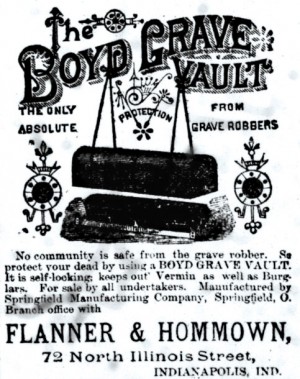

Many tactics were employed to protect the bodies of relatives, mostly to no avail. Police were engaged to watch the burying grounds but were often bribed or made drunk. Spring guns, or booby-traps were set in the coffins but was an option available only to the wealthier citizens. Poorer families would leave items like a stone or a blade of grass or a shell at the head of the grave to show whether it had been tampered with or not. During this era, “Burglar proof grave vaults made of steel” were sold with the promise that loved ones’ remains would not be one of the 40,000 bodies “mutilated every year on dissecting tables in medical colleges in the United States.” Despite these efforts, body snatchers persisted.

In the late 1800s in Indiana, it has been estimated that between 80 to 120 bodies each year were purchased from grave robbers to be used for medical instruction at medical schools and teaching facilities in Indianapolis. An end to the “big business” of grave robbing came as a result of 20th century legislation in Indiana which allowed individuals to donate their bodies for this purpose. In 1903, the Indiana General Assembly enacted legislation that created the state anatomical board that was empowered to receive unclaimed bodies from throughout the state and distribute them to medical schools. The act was “for the promotion of anatomical science and to prevent grave desecration.”

Before that landmark 1903 legislation, Indiana medical schools had access to only one type of corpse for dissection — the bodies of executed criminals, which provided a fairly small pool of available subjects. Only 9 people were executed in Indiana from 1897 to 1903, not nearly enough to supply the medical schools of the city. Strangely, there were 41 lynchings over the same period (26 whites and 15 blacks). As the number of medical students in Indiana grew, the demand for bodies for dissection became greater. As there were simply not enough bodies legally available, medical schools resorted to back door arrangements with resurrectionists. Occasionally, the grave robber was a doctor, teacher or medical student. For the most part, the medical community wrestled with the morality issues surrounding the procurement of corpses for dissection purposes, but it cannot be denied that the practice yielded dividends. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the United States led the world in advances made by anatomical studies through the use of the cadaver appropriation system.

By the way, on special occasions during the Irvington ghost tours, I sometimes bring along a battered, faded sepia-toned cabinet photo from the 1880s. In this photo, several University of Michigan medical students are posed standing around an emaciated, nearly naked corpse splayed out on a wooden table. The students pose somberly for the camera but one of them, a handsome derby hat wearing young man with a large walrus style mustache, stands with one hand behind his back and the other with fingers resting on the table surface near a pocket knife that he has obviously just pulled from his pocket. His expression seems to say, “Hurry up and snap that photo so I can cut into this body.” The subject? Michigan medical student Herman Mudget, better known as H.H. Holmes, America’s first serial killer.

Next week: An Indiana body snatching connection to the United States Presidency and Irvington.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest books are “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View,” “Irvington Haunts. The Tour Guide” and “The Mystery of the H.H. Holmes Collection.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.