There has been a lot of talk lately about Confederate Civil War monuments and what they stand for. In fact recently, several of those monuments to rebel leaders and soldiers were toppled by protesters and removed in the dark of the night by officials. My wife and I travel to Gettysburg 2 to 3 times every year and a fairly wear out my Facebook friends with the many pictures I post from that famous battlefield. The monuments on the Gettysburg battlefield had escaped the relevant racial scrutiny and have often been viewed as untouchable and different from the ones being protested across the nation until last week when the debate hit the pages of the Gettysburg Compiler newspaper.

Scott Hancock, an associate professor of History and African studies at Gettysburg College, says it may be time to question the Confederate monuments on the Gettysburg battlefield. “As an African American, I’m glad for one that we seem to have a broader public movement consensus of people that want to get the history right,” Hancock said.

Hancock explained that, in the last decade or so, a majority of historians have concluded that slavery was the central issue of the Civil War. As a result, the monuments dedicated to the Confederacy and Confederate figures represent a “narrow, twisted version of history,” Hancock said. For some, the Confederate monuments on the battlefield help tell the full story of the Battle of Gettysburg. If nothing else, Hancock’s story begs the question: Is there a difference between Confederate monuments found in public parks and those found on battlefields? What about Confederate monuments in cemeteries?

The root of the question may be historical context. Should Confederate soldier’s sacrifices, and in many cases their deaths, be recalled and remembered at the spot of their struggle? In my opinion, the battlefield monuments to both sides speak to all who view them. Not only do they represent the soldiers that fought there, they are also valuable pieces of public art. Often, they are made of stone native to that soldier’s state or placed upon a sacred spot of battlefield relevance.

One need only look as far as Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address to understand why those monuments are placed there. Lincoln said, “Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

To most Americans that should be reason enough to leave the Confederate Civil War monuments found on battlefields and in cemeteries in place. The question is not only consigned to the Gettysburg battlefield however. Indianapolis, although never the scene of a major Civil War battle, has monuments to Confederate dead as near as Garfield Park and Crown Hill Cemetery. Undoubtedly, the question of whether or not they should remain there will be debated soon.

The argument as to whether these monuments are part of our cultural landscape will most likely continue. As for their presence on battlefields and in cemeteries, these site-specific memorials were designed to be educational markers to interpret history. From Professor Hancock’s perspective, is it appropriate to have markers of any kind honoring the Confederacy placed on public land and maintained by public money? For the record, that debate goes on within the Hunter household. But, I guess I’m just a late stage baby boomer who grew up during the Cold War and who is proud to have been born during the centennial celebration of the Civil War. So I guess it’s a generational thing.

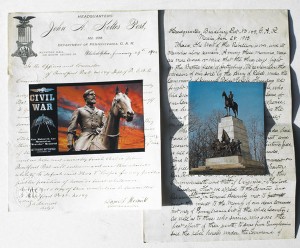

I’m not prepared to make a personal political statement in this article but I did want to share an item from my collection that I feel speaks to the issue from a different perspective. Among the many collections I obsess over is my gathering of items of all sorts relating to the battle of Gettysburg. One such item is a set of documents I bought several years ago from January 1903.

One is a two-page handwritten document on legal sized paper from the Grand Army of the Republic (G. A. R.) Headquarters post Bradbury Pennsylvania near Philadelphia dated January 28, 1903. The official resolution document reads: “Whereas the War of the Rebellion is over, and its memories alone remain. Among these memories none are more sacred or vivid than the three days fight on the Battlefield of Gettysburg. We remember the invasion of our soil by the Army of Rebels under the command of General Robert E Lee. Three days we fought the faux under the command of one who had sworn to support the Constitution and Sons of Our Country. Who had been educated at the nation’s expense, and honored by all the people: yet who in the hour of the country’s need proved himself an Arch Traitor.

“What Gettysburg is we and our comrades have made it. The glory, the fame, the sentiment and reverence that cluster around that historic field, is all ours, and that of our fallen comrades. And whereas, it is proposed to erect a monument on the field of Gettysburg to the memory of this traitor Gen. Robert E Lee, at the joint expense of this Commonwealth and that of Virginia.

“Therefore resolved, that we appeal to the Senators and Representatives of Pennsylvania in General Assembly met to defeat this insult to the memory of our dead comrades not only of Pennsylvania but of the whole country; as well as to those who survive, who gave the best efforts of their youth, to drive from Pennsylvania’s soil, the rebel hordes under the command of the Rebel General, to whom it is now proposed to honor.

“Resolved. That Thomas V. Cooper, a comrade of this post in presenting this bill and favoring its passage, voices but one comrade and does not speak for post-149. Resolved. That a copy of these resolutions under the seal of the post attested by the commander and adjutant, be sent to the Senate and House of Representatives of the State: and a copy of the same, sent to Headquarters of This Department.” The document is signed by three members of the post, (Thos. J. Dolphin, O. F. Bullard, & James H Worrall) — all of whom I’m sure were former Union soldiers.

The other is an 8.5 x 11 handwritten letter dated January 29, 1903 on the ornate letterhead of the “Headquarters John A Koltes Post No. 228 Department of Pennsylvania, G. A. R. Keystone Hall, 835 North Second St., Philadelphia” the letterhead features an image of the G.A.R. soldier’s badge at the top. The letter reads: “To the Officers and Comrades of Bradford Post No 149 Department of Pa. G. A. R. Comrades! The following resolution was unanimously adopted at a regular slated meeting of the above named Post, and I take pleasure in transmitting a copy thereof to you as directed. Namely, that we heartily congratulate our brave comrades of Bradford Post No 149 the action they have taken so far regarding the erection of a memorial statue to Robert E Lee on the Battlefield of Gettysburg, through the apparent willingly given assistance of one of those members, Representative Thomas V Cooper, and we hope and earnestly trust, that in future Bradford post will endeavor and use the utmost ability to defeat said Thomas V Cooper for any further public position of honor or trust whatsoever. Resolved that a copy of this resolution be transmitted to Bradford Post No 149. Daniel L Hornick Commander.”

The letters illustrate that this debate was going on 40 years after the close of the Civil War and was being waged by the soldiers who participated in it. Think about the strife and turmoil that must’ve been swirling within the walls of this lodge as they protested the placement of the statue to the Rebel General they fought so bravely against. The ex-soldiers were so vehement in their opposition that they were willing to take on one of their most accomplished lodge members, Senator “Red Headed and Hopeful” Tom Cooper.

Cooper served as a delegate to the 1860 Chicago Republican Convention and played a pivotal role in the nomination of Mr. Lincoln. At the outset of the Civil War, Thomas helped organize Company F of the Fourth Pennsylvania Regiment and later enlisted in Hartranft’s Company C, 26th Regiment, serving three years in the Army of the Potomac. He mustered-out at Independence Hall, June 14, 1864, having served in 13 major engagements, including Second Bull Run, Chancellorsville, Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, the Wilderness, and Spotsylvania Court House. Thomas represented Delaware County in the State House of Representatives, 1870-72, and was elected to the state Senate in 1872. He served 17 consecutive years in the upper house. Cooper was a Mason, a member of the Bradbury G.A.R. Post . Cooper died in his home on December 19, 1909 after a freak fire engulfed his room, most likely, the result of an ash falling from his trademark cigar. Cooper had as much right to protest the placement of the Robert E. Lee statue as anyone. His patriotic credentials were unquestioned. Yet he supported the placement of a Confederate monument on a battlefield he risked his life fighting on.

Despite the Bradford Post’s attempt to thwart the placement of the Lee Monument at Gettysburg, the iconic landmark was indeed placed there in the days just before World War I. The Virginia monument, located on West Confederate Avenue, was the first of the Confederate State monuments at Gettysburg. It was dedicated on June 8, 1917 and unveiled by Miss Virginia Carter, a niece of Robert E. Lee. It is the largest of the Confederate monuments on the Gettysburg battlefield, a fitting tribute for the state that provided the largest contingent to the Army of Northern Virginia, its commander, and its name. Lee’s figure, topping the monument astride his favorite horse, Traveler, was created by sculptor Frederick Sievers from photographs and life masks of the general. He even went to Lexington, Virginia to study Traveler’s skeleton, preserved at Washington and Lee University. The monument stands 41 feet high. The statue of Lee and Traveler stands 14 feet high. The total cost of the monument was $50,000. Virginia contributed over 19,000 men to the Army of Northern Virginia at Gettysburg, the largest contingent from the twelve Confederate states. Almost 4,500 of these – almost 1 out of 4 – became casualties, the second highest state tota at Gettysburg.

When it comes to the battlefield, Hancock pointed out that, while most of the park’s monuments and markers were constructed in the late 19th and early 20th century, several Confederate memorials were erected in the 1960s and 1970s. Hancock points out that many of those monuments to the Confederacy were erected before, during and after the Civil Rights movement and deserve particular scrutiny “because of the social and racial context of the time.” Hancock singled out the Confederate monuments along Confederate Avenue, in particular that of Mississippi, which was erected in the early 1970s. The monument speaks of Mississippians fighting for the “righteous cause” and “sacred heritage of honor.”

Voices on both sides of the issue will certainly attempt to add clarity in the days ahead. For instance, former Martin Luther King Jr. right-hand man, UN representative under Jimmy Carter and Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young recently said, “I think it’s too costly to continue to fight the Civil War.” Condoleezza Rice, former Secretary of State under George W. Bush, said, “When you start wiping out your history, sanitizing your history to make you feel better, it’s a bad thing.” The debate promises to continue. But let’s not forget this is a debate that has been going on for over 150 years now.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest book is “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.