Often visitors to the Bona Thompson Memorial Center will ask me, “What can you tell me about my house?” And I’ll answer, “What is your address? There may be a little information or a lot.”

One of the best resources for information about a house is contained in the abstract of title, and there are a number of these documents in the collection of the Irvington Historical Society from Irvington area houses. But what is an “abstract of title?” The document, that may appear to be a bundle of rolled-up papers held together by brass colored fasteners, is simply a chronology of the ownership of a piece of property. From this document one can learn the owners of the lot upon which a house sits, but not the residents of the house unless the resident is also the owner.

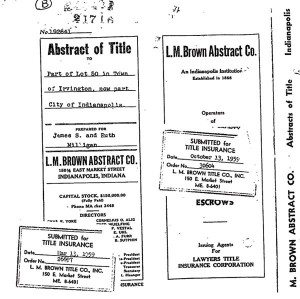

Abstracts of Title were prepared by Indianapolis companies such as the Union Title Company and the L. M. Brown Abstract Company for a homeowner at the time of sale to show that the owner has “clear title” to the property (that there are no other claims to the land). These documents were common before the advent of title insurance.

So, how do you read an Abstract of Title? In many cases, instead of an address on the cover of the document there is a legal description of the property that relates to the developer who bought a parcel of land and platted it — laid out the lots and streets — and recorded this action with the county recorder. Usually there is a map with the abstract that shows the unique location of the lot within the platted addition.

The next entry is a history lesson. The title to the land of all real estate in Marion County, Indiana originally comes from the United States. However, the title’s origin began much earlier with the European explorations and discoveries of the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Ponce de Leon, and Hernando de Soto made vast claims for Spain; Jacques Cartier, and Sieur de La Salle made vast claims for France; and John Cabot made vast claims for Great Britain. Little thought was given by these claimants to the claims of Native Americans.

By terms of the Treaty of Paris which ended the Seven Years War (French and Indian War), signed on February 18, 1763, France ceded all lands that would eventually become the state of Indiana to Great Britain. The title that Britain received in this cession was passed to the United States at the conclusion of the American Revolution when another Treaty of Paris was signed on September 9, 1783, but claims to the lands north of the Ohio River by Virginia, Connecticut, New York, and Massachusetts had to be resolved. Eventually Virginia was recognized as the only valid claimant, and that state transferred these lands to the United States in 1784. The Territory Northwest of the Ohio River (the Old Northwest Territory) was established on July 7, 1787 to provide for the orderly transfer of Native American land claims to the United States and for surveying the area for settlement. On May 7, 1800 the Indiana Territory was organized, and through treaties negotiated by agents of the United States with Native Americans, land encompassing large swatches of what is now eastern and southern Indiana opened to settlement.

Indiana became a state on December 11, 1816, and soon after the Treaty of St. Mary’s (October 6, 1818) saw the Wea, Delaware, Miami, and Kickapoo tribes give up their land claims in the vast central region of the state. Soon thereafter, settlers began to enter the “New Purchase” and register their land claims with the district land office in Brookville, Indiana paying $1.25 per acre (2014: $21.90). If the land selected by an individual was clear of other claims, the United States government would then issue a patent describing the land, based on the original government survey, to the individual thereby conveying a portion of public land into private ownership. Such was the case when Jacob Sandusky entered the southeast quarter of Section 3, Township 15 North, Range 4 East on January 21, 1822 and later on April 10, 1823 received his patent or grant for 160 acres in Marion County’s Warren Township, west central region.

An abstract describes further transfer of property by the original owner (grantor — i.e., seller) to a subsequent owner (grantee — i.e., buyer) through a warranty deed (a guarantee that the seller has clear title to the property and a right to sell). Sometimes the transfer of property is by a quitclaim deed which carries no such guarantee.

A later entry will show that all or a portion of the original parcel has been purchased by a developer, i.e., Jacob B. Julian and Sylvester Johnson, who had the land surveyed and platted into lots for public sale. The name of the plat, i.e., Plat of Irvington, and the terms of any conditions (covenants) placed on land will be listed in the abstract either separately or as part of the warranty deed. Once again, the lots are sold by warranty deed. Often a lot is mortgaged. While this action often indicates that the buyer is securing additional funds to improve the lot generally with a house, it may also be that the lot was mortgaged as security for funds to purchase the lot.

An abstract usually will show that a platted lot has been subsequently subdivided into smaller lots, and a plat of this subdivision will have been recorded, too. The lot that your house is on will probably be a part of this last action.

Miscellaneous entries such as wills and other contributing information from individuals about the early property owner are often part of an abstract. The status of tax payments, public improvement assessments, liens, and bankruptcies may also be found in an abstract.

Abstracts of title should be kept in a secure place and passed from homeowner to homeowner as a record of the property’s history. If you would like to loan an abstract to the Irvington Historical Society so that a copy can be made for inclusion in the society’s collection, please e-mail me at irvingtonhistoricalsociety@yahoo.com.