On this 150th anniversary month of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, Al Hunter is off chasing Lincoln for future stories. Here is an encore of an article from April 20, 2010.

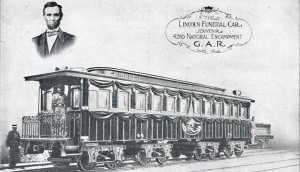

Anyone familiar with my writings and ramblings knows that I have one special “obsession” when it comes to ghost stories; The Lincoln Ghost train. I’ve written countless articles, papers and literary works on the life and death of Abraham Lincoln over the past 15 years or so. On April 30th, 2015 it will mark the 150th anniversary (to the day) that the Lincoln train visited Indiana on its way to Springfield, Illinois. The Lincoln Ghost Train is consistently the most asked for story on the October ghost tours and the event that gathers the most attention from admirers and devotees of the 16th President all year round.

When the train came through Indiana, the official Travel Log of the train notes that it arrived in Greenfield at 5:48 a.m., Philadelphia at 5:57 a.m., Cumberland at 6:30 a.m., the “Engine House” (identified as “Thorne” in Irvington) at 6:45 a.m. before finally arriving in Indianapolis at 7:00 a.m. The previous day’s rain had stopped just after midnight as the train approached the Indiana border, revealing a beautiful starlit sky as a backdrop for the sad processional and lifting the hopes of the trackside witnesses. However, the telltale slap/pop sound of hard raindrops hitting roofs and roads began again in the predawn hours and by 6 a.m., a pelting blanket of rain blanketed the Hoosier countryside. Although it was dark and rainy, the area along the tracks was well lit by torches and bonfires tended by loyal Lincolnites as the train crept towards Indianapolis at less than 10 miles per hour.

In Greenfield, the depot was choked with people wishing to gaze upon the face of the departed leader one last time. The train was not officially scheduled to stop in Greenfield, but the mood among the citizens was that perhaps the engineer might be persuaded to stop when he witnessed the tremendous outpouring of trackside emotion at the Greenfield depot. The local newspaper described among those expectant gatherers “a knot of three boys, hands in pockets chattering back and forth with each other while pacing up and down the railroad tracks. Two older fellows were standing together, each arm around the other, probably soldiers remembering what it means to be a comrade.” The depot porch was filled to overflowing with women in their long dresses, old soldiers in their Union uniforms and a sea of men dressed entirely in black. The telegraph operator in Charlottesville wired that the train had just passed and was heading towards the neighboring town.

A sentinel was perched atop the station to alert the citizens below of the train’s approach. In a few moments, a cloud of silver phosphorescent smoke appeared above the tree tops that parallels the exact route of the present day Pennsy trail. “Here it Comes” was the cry from above and immediately the crowd below hushed and gazed eastward expectantly. For several moments, the only sound that could be heard on the platform was the muffled weeping of the gathered mourners. The crowd asked Captain Reuben Riley to read aloud excerpts from Lincoln’s second Inaugural address as the train slowly approached. As if in response to the impromptu ceremony, the train paused briefly at the station and the engineer removed his cap in respect to reverent gathering.

Reverend Manners stepped from the crowd and led the group in a prayer that began with “Thank God for the life of Abraham Lincoln.” The people now openly wept as the 10 car train departed westward towards Indianapolis. Unfortunately, there are no witness accounts from the train’s sojourn through Irvington. Other towns and cities along the route were bedecked in black mourning cloth, lit by trackside bonfires and oil lamps with platforms choked with adoring masses.

The train came to it’s final west bound destination under cover of a sheltered structure at Union Station in the Hoosier Capitol City. As the train arrived, guns were fired every minute, every city bell chimed continuously, and the Indianapolis city band played dirges at trackside. The train slowed to a stop as the smokestack puffed and hissed under the massive hipped roof of the old station, enveloping the platform and gathered dignitaries in a ghostly fog. As the final slow hiss of boiler steam escaped form the bowels of the Lincoln funeral train, the President of Chicago & Indiana Central Railway, D.E. Smith issued the following telegraph, “The funeral train arrived here precisely on time. There was a perfect torchlite along the along the whole route. Every farm house had its bonfire in order to see the train. Urbana, Piqua, Greenville and Richmond turned out their entire population. Nearly every town had arches built over the track.”

Extensive preparations had been made for receiving the President’s remains that Governor Oliver P. Morton decreed were to be “Consistent with the dignity and reputation of the state.” While Morton planned the festivities meticulously, he could not control the weather. As the daybreak rains poured forth, the bunting and other mourning signs and decorations were soaked and in most places sadly dragging on the ground. However, the rains did not deter the sorrowful pilgrimage of mourners packing the streets from Union Station to the Statehouse. The military guard was drawn up in a solid blue line on both sides of the street, posed with bayonets forward for five blocks from Illinois up Washington Street to the Statehouse doors. The heavy rain forced the cancellation of a much larger, planned official processional. Lincoln’s body was transferred by a guard of honor from the train into an hearse topped by a silver-gilt eagle, drawn by six white horses with black velvet covers, each bearing black and white plumes.

The body was escorted by Governor Morton and General “Fighting Joe” Hooker to the Indiana State House. Legend claims that we owe the title affixed to present day “ladies of the evening” to Gen. Hooker, an avowed ladies man. As proof of his attraction to the opposite sex, when the coffin was opened in preparation for public viewing, Hooker observed eight rosebuds clinging to the dead President’s body inside. He carefully plucked the flowers, believed to have been placed there while the body was in New York, and distributed them personally among several ladies present for the ceremonies. These women prized the memory of the encounter as well as the flowers for decades after the event.

News traveled slowly in those days and Indianapolis was the first major city to hear the news that the President’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, had been captured and killed and the news buzzed through the excited crowd as they waited outside in the rain. The doors were opened at 9 a.m. as an estimated 120,000 people passed by Lincoln in less than 13 hours of public viewing. Roughly 155 people per minute (or 9,300 Hoosiers an hour) passed by the open casket as it rested in the old Capitol Building. By the time Mr. Lincoln’s body arrived in Indianapolis, his face was almost black from decomposition. A local newspaper reporter wrote that Lincoln looked, “…a good deal discolored and emaciated — wearing a haggard and careworn look, but otherwise rather natural.”

Perhaps the most noteworthy visitors that day were the “Colored Masons” who formed a respectable procession lead by a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation and carrying banners reading “Colored Men, always loyal” and “Slavery is dead.” By 9 p.m., the crowds diminished, allowing those remaining mourners the luxury of having a long look at the remains. The doors of the State House were ordered closed at 10 p.m. and once again the soldiers were assembled and posted along the return route to Union Station. At 11:50 p.m. the Lincoln train left Indianapolis bound for Chicago. During the night the train passed through Augusta at 12:30 a.m., Zionsville at 12:47 a.m., Whitestown at 1:07 a.m., Lebanon at 1:30 a.m., Thorntown at 2:10 a.m., Lafayette at 3:35 a.m. and Battle Ground at 3:55 a.m. In Michigan City at 7:40 a.m., an impromptu funeral was held and Mr. Lincoln’s coffin was opened one last time in the Hoosier State as mourners filed through the Lincoln train car to view the dead President.

The Indianapolis Daily Sentinel reported in the May 1, 1865 edition of the newspaper that the ceremonies of the previous day, “All in all the multitude presented the most grotesque and ridiculous appearance we have ever witnessed. Wet, tired, cold and famished, beduabed with mud and filth, they presented a sorry sight indeed. No more inclement and uncharitable day could have been, and no more enthusiastic mass of sightseers could have been collected together.” Ironically, while the crowds waited in the rain soaked muddy streets for a last glimpse of Lincoln, pickpockets worked the crowds. It wasn’t all chivalry and solemnity, folks.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest book is “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.