Where were you 40 years ago? February 1974 was a busy month in pop history. “Good Times” (a spin-off from “Maude”) premiered on CBS TV, Barbra Streisand’s “The Way We Were” became her first Number 1 hit, Patty Hearst was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army, and the U.S. House of Representatives began determining grounds for impeachment of Nixon during the Watergate scandal, Oh, and on February 22, 1974, an unemployed former tire salesman hijacked a plane and tried to kill Richard Nixon.

Samuel Joseph Byck was born on January 30, 1930 to poor Jewish parents in South Philadelphia. Byck dropped out of high school in the ninth grade in order to support his impoverished family. He enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1954, was honorably discharged in 1956, married shortly thereafter, and had four children. In 1972, after years of jumping from job to job, Byck began to suffer from severe bouts of depression and his wife divorced him. Citing depression, Byck admitted himself to a psychiatric ward where he stayed for two months.

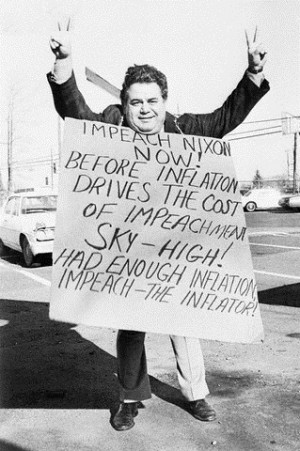

Soon after arriving, Byck began to harbor the belief that the government was conspiring to oppress the poor. The Secret Service turned their attention to Byck in 1972 after Sam threatened President Richard Nixon through the U.S. Mail. Byck had harbored a deep, personal resentment towards Nixon ever since his Small Business Administration had turned him down for a business loan. Twice, he turned up outside the White House carrying placards protesting Nixon’s presidency; he was arrested both times for protesting without a permit. He later dressed in a Santa suit for yet another protest shouting and carrying a sign saying “All I want for Christmas is my constitutional right to publicly petition my government for a redress of grievances.” Although an exceptionally cogent slogan, it was created by a man who was quickly losing his grip on reality.

In time, Byck made tape recordings about the injustices he believed he had suffered at the hands of the Nixon administration; in particular, that denial of a federal loan to start a mobile tire business. Astonishingly, the Secret Service decided these were idle, harmless threats posed by an unbalanced man. Byck began to send his bizarre rambling tape recordings to various public figures including scientist Dr. Jonas Salk, Connecticut Senator Abraham Ribicoff, baseball great Hank Aaron, baby doctor Dr. Benjamin Spock, journalist Jack Anderson, and his personal hero, composer Leonard Bernstein. Pudgy, pasty-faced Sam Byck even tried to join the Black Panthers. Still, the Secret Service considered Byck to be harmless, and once again, took no action. In 1973, Byck started to develop a plan he called “Operation Pandora’s Box.” That plan was to assassinate Richard Nixon. In one of his tape recordings Byck warned that, “This government does not have the ability to cleanse itself and I will cleanse it by fire.”

By early 1974, Byck planned to assassinate the President by hijacking an airliner and crashing it into the White House on a day when Nixon would be there. It has been suggested that Byck was inspired by news reports of the February 17, 1974 buzzing of the White House by Army PFC Robert K. Preston in a stolen helicopter, a subject we covered in Part I last week. Regardless, Preston’s feat must surely have brought a smile to the face of the unhinged unemployed tire salesman from Philly.

Since Byck was already known to the Secret Service, and because legal attempts to purchase a firearm might have resulted in increased scrutiny, Byck stole a .22 caliber revolver from a friend of his to use in the hijacking. Byck also made a bomb out of two gallon jugs of gasoline housed in Valvoline oil bottles rigged with a crude igniter switch. All through this process, Byck made audio recordings explaining his motives and his plans; he expected to be considered a hero for his actions, and wanted to fully document his reasons for the assassination. Here’s a typical excerpt from one of those tape recordings, “Allow me to introduce myself — my name is Sam Byck. I intend to . . . gain entrance to the cockpit of a commercial airplane. I intend to instruct the pilot to fly the plan to the target area. I intend to shoot the pilot and fly the plane into the Executive Mansion.”

On February 22, 1974, 44-year-old Sam Byck drove to the Baltimore/Washington International Airport armed with a .38-caliber revolver. There he shot and killed 24-year-old Maryland Aviation Administration Police Officer George Neal Ramsburg before storming aboard a DC-9, Delta Air Lines Flight 523 to Atlanta, which he chose because it was the closest flight that was ready to take off. Poor Ramsburg never had a chance — he was looking the wrong way when this mentally ill loser walked up behind him and shot him dead. After pilots Doug Loftin and Fred Jones told him they could not take off until wheel blocks were removed, he shot them both and grabbed a nearby passenger, ordering her to “fly the plane.”

Jones died as he was being removed from the aircraft after the event; Loftin survived the attack and resumed flying airliners three years later. Byck told a flight attendant to close the door or he would blow up the plane. Anne Arundel County Police officers attempted to shoot out the tires of the aircraft in order to prevent it from taking off, but the .38 caliber bullets fired from the Smith & Wesson revolvers issued to the officers at that time period failed to penetrate the tires of the aircraft and ricocheted off, some hitting the wing of the aircraft.

After a standoff with police, Charles Troyer, an Anne Arundel County police officer on the jetway, stormed the plane and fired four shots through the aircraft door at Byck with a .357 Magnum revolver taken from the deceased Ramsburg. Two of the shots penetrated the thick window of the aircraft door and wounded Byck. Before the police could gain entry to the aircraft, Byck committed suicide by shooting himself in the head. Byck lived for a few minutes after shooting himself, dying after saying “help me” to one of the police officers. A briefcase containing the gasoline bomb was found under his body. At the moment of Byck’s death, Nixon was actually in the Executive Mansion hunkered down in mid-Watergate. The plane never left the gate, and Nixon’s schedule was not affected by the assassination attempt. However, it was after this episode that a bunker was built in the bowels of the White House, and large guns were placed on the roof of the White House.

Though Byck’s attempt lacked the skill and self-control to reach his target, it did provide a chilling reminder of the potential of violence from the sky. After Byck’s death, his assassination plot remained relatively unknown, except among members of the U.S. Secret Service. Byck quickly faded into obscurity and soon Nixon fell on his own sword of Watergate. But the terrifying memory of Samuel Byck’s misguided scheme resonates in every American’s mind whenever the thought of 9/11 visits our nightmares. On page 561 of the 9/11 Commission Report, the attorney mentions Byck’s attempt when he explained why he thought that a fueled Boeing 747, used as a weapon, “must be considered capable of destroying virtually any building located anywhere in the world.” No doubt, Sam Byck was a broken man whose mind worked with all the efficacy of a broken clock. But one must never forget that even a broken clock is right twice a day.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.