Sixty-five years ago, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. came to Indianapolis to speak at the Cadle Tabernacle radio ministry in downtown Indianapolis. For nearly half a century beginning in the 1920s, the massive building sat roughly two blocks east of the old Indianapolis City Hall. The Spanish Mission style facility occupied nearly an entire city block and looked more like the Alamo than a church.

The 10,000-seat Cadle Tabernacle, which at that time was the largest church in the United States, had hosted nearly every famous evangelist from Billy Sunday to Oral Roberts. The station’s signature program, “Nation’s Family Prayer Period” complete with a 1,400-voice choir, was broadcast all over the midwest from WLW in Cincinnati every Sunday morning. Given the station’s massive broadcast range, it is estimated that 30 million people heard the program every week. The radio ministry was presided over by E. Howard Cadle, who had built the tabernacle in 1921. He named the Tabernacle in honor of his mother, Etta Cadle, to whom he gave credit for bringing him back into the fold of Christ after a youth of drunkenness, gambling and sin.

Cadle was born in Fredericksburg, Indiana in 1884 and by the time he built his masterpiece at the corner of Ohio and New Jersey streets, he had lost and remade several fortunes in a variety of businesses, including a chain of while-you-wait shoe repair shops. Cadle’s brushes with poverty prompted him to distribute radios all over the midwest, near South and in many small Appalachian communities that were too small to have their own church within walking distance. Rural communities too poor to afford a minister listened Sunday mornings on the radio installed on their church pulpit by a member of Cadle’s outreach team. Flying in a plane piloted by his only son Buford, Cadle often visited his supporters around the country for “one-night revivals.”

When E. Howard Cadle died in 1942, his son Buford continued to operate the tabernacle for another quarter century, expanding the venue’s range by hosting both religious and non-religious events. Those events included Ku Klux Klan meetings, prize fights and dance competitions. The younger Cadle was at the helm when 29-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. spoke there on Dec. 12, 1958. But perhaps the first thing most Hoosier historians recall about the Cadle Tabernacle was its connection to beloved Hoosier actress, Carole Lombard.

It was at the Cadle on January 15, 1942 (ironically Martin Luther King, Jr’s 13th birthday) that Miss Lombard led visitors in singing the Star Spangled Banner after raising funds for the war effort at the Statehouse earlier in the day. Lombard sold a record $2,017,513 in War Bonds in one hour, with each buyer receiving a red, white and blue receipt bearing Lombard’s likeness and signature, along with the message: “Thank you for joining with me in this vital crusade to make America strong.” She continued to urge sales later that evening also at Cadle. It turned out to be the last night of her life.

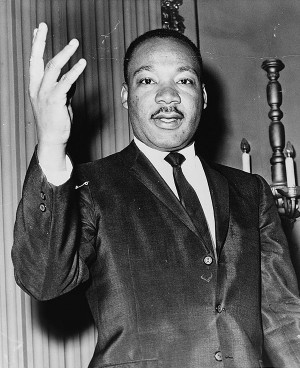

Yes, the Cadle Tabernacle had established quite a varied history by the arrival of the young pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. The humble preacher was already accruing an impressive resume. The speech came three years after King had gained international fame as the spokesman for the Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott. The Civil Rights movement as we know it today got its start in Montgomery when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man on Dec. 1, 1955. The boycott lasted nearly a year and ended with the U.S. Supreme Court’s Browder v. Gayle decision overturning Alabama’s bus segregation law.

By the time of King’s arrival at the Cadle, he had founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and published a book, Stride Towards Freedom, about the Montgomery boycott. King was invited to speak that day by the Indianapolis “Negro” YMCA organization for one of their “Monster Meetings.” These Monster meetings were defined as “focal points for protest and constituent education” sponsored by traditional African American owned and operated YMCAs. As an arm of the Monster Meetings, the Citizen’s Committee of One Hundred, scrutinized pending legislation and other city and state activities that were likely to have a negative impact on housing, education, and employment in the black community. Further, the Monster Meetings played a central role in galvanizing the community around such important issues as the relaxation of racial restrictions at Indiana University, the opening of downtown theaters to blacks, the integration of the Indiana High School Athletic Association, preparation of the Anti-Hate Bill that became law in 1947, employment of blacks in the city administration, and preparation of the Anti-Segregation Bill that became law in 1949.

Each of these issues was discussed in open forums and reported on by knowledgeable, interested individuals and the appropriate committees. Committee reports were often made directly to the Monster Meeting audiences with the confidence that every organization interested in matters affecting the race was represented there. It is interesting to note that the two “Monster Meeting” speakers immediately preceding Dr. King were Jackie Robinson (1/28/58) and Thurgood Marshall (3/9/58) and the speaker immediately following King was Roy Wilkins (3/1/59).

King spoke to an estimated crowd of 3,800 people that cold Friday night. The official YMCA “Monster Meeting” log notes that the Martin Luther King, Jr. speech was titled “Remaining Awake through a Revolution” for which he received a $500 honorarium. Curiously, that same official record notes the live audience as being 1,100 in attendance. Joining King at the podium were Indianapolis Mayor Charles Boswell and his friend, the Rev. Andrew J. Brown, pastor of St. John Missionary Baptist Church at 17th and Martindale and one of the founders of Black Expo in 1970.

Fremont Power covered the speech for The Indianapolis News. According to his story King told his audience “a new world is being born” and that blacks must avoid bitterness over the past. “We must learn to live together as brothers,” he said, “or we will die as fools.” “Segregation,” King said, “is nothing but slavery covered up by certain niceties and complexities. We know that if democracy is to live, segregation must die.” King’s speech was so well received that he was asked to return almost exactly one year later on December 11, 1959. Here he gave a speech titled: “Remaining Awake through a Revolution” for an estimated crowd of 1,000 in the new Fall Creek YMCA.

King again returned to Indianapolis on Nov. 24, 1961, to speak to the Southern Christian Leadership Council. By the time of Dr. King’s assassination, the Cadle Tabernacle was in need of extensive repairs and a buyer was making a convincing pitch to buy the land. On Nov. 1, 1968 it was announced that Cadle Tabernacle would be torn down. The new Indiana National Bank tower was under construction just three blocks away at Pennsylvania and Ohio streets and they wanted the land for an employee parking lot. By the end of that year, Cadle Tabernacle had disappeared. The Cadle family and a network of associates sustained their radio ministry, broadcasting into the early 1990s, long after the tabernacle building’s demise. Since 2001 the old Tabernacle property is home to an upscale townhouse development known as Firehouse Square.

Yes, 65 years ago this week, Dr. King appeared in Indianapolis at the Cadle Tabernacle at the tail end of a speaking tour. What goes unnoticed about his appearance in our fair city is the fact that while here, Martin Luther King, Jr. was on doctor’s orders to take it easy. Why, you may wonder? Three months earlier, on September 20, 1958, while at a book signing in Harlem, New York, King was nearly assassinated. No need to recheck the date. A decade before he would die at the hand of a cowardly white supremacist at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, Martin Luther King, Jr. would nearly lose his life. But this time the weapon would be a common household object wielded by a fan — a 42 year old mentally disturbed black woman named Izola Ware Curry.

Next Week: Part 2: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Indianapolis.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.