While the joyous celebrations of Easter were quickly fading into memory, the promise of Spring with the burst of blooms in orchards, the budding of trees, and the carpet of wildflowers in the woodlands continued to lift the spirits when the Crisis finally broke on April 12, 1861 with South Carolina artillery bombarding Ft. Sumter in Charleston harbor. News of the attack on the nation’s flag and the fort’s surrender reached Indiana on Sunday, April 14. Spontaneous public meetings of Unionists — Republicans, Democrats, men of all parties — met around the state and these Hoosiers of all ages began forming military companies. The following day, Gov. Oliver Morton telegraphed President Lincoln pledging 10,000 troops “for the defense of the nation and to uphold the authority of the government.” Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers that same day assigned Indiana’s quota at six regiments (4,683 men) for three months service. The Governor’s proclamation called upon patriotic men of Indiana to form companies, come to Indianapolis, and report to the state’s newly appointed Adjutant General, Lew Wallace, at the new state fairgrounds north of the city (1900 block of N. Alabama St.). With its buildings and barns, it was a perfect site to house the companies that were beginning to come into Indianapolis. Organized companies from around the state soon began arriving along with individual volunteers seeking to join a company. In a week’s time, 12,000 men — three times the state’s quota — were in Camp Morton. While the 36-acre site was spacious, shelter for the troops quickly became an issue as the fairground permanent structures quickly filled. In addition to their prayers, the ladies of the city provided blankets and bedding. Surgical supplies — lint and bandages — were also provided.

Spring rains turned the grounds into a vast, intolerable mud-hole and the effects of the bad weather and close quarters began to show with the appearance of pneumonia, typhoid, and measles. With dozens of companies and a score of regiments struggling with deteriorating conditions at Camp Morton, a second camp was established in mid-May 1861 on the former site of the state fairgrounds (Military Park), west of the State House. It was named Camp Sullivan in honor of Col. Jeremiah C. Sullivan, commanding officer of the 13th Regiment.

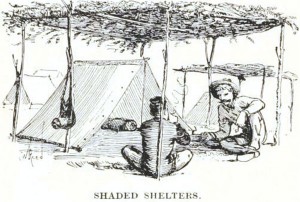

A third camp was established at the beginning of June when the 8th Regiment, with volunteers from Wayne, Grant, Randolph, Delaware, Madison, Henry, Hancock, and Wabash Counties, under the command of Col. William P. Benton, and the 10th Regiment, with volunteers from Tippecanoe, Warren, Clinton, Clay, Montgomery, Putnam, Boone, and Marion Counties, under the command of Col. Mahlon D. Manson, left Camp Morton on Saturday, June 1, 1861 and marched five miles east of the city to the Jacob Sandusky farm (a place that within a decade would become the town of Irvington), and entered a campsite along the north side of the National Road, occupying “beautiful” open ground, but with few shade trees, along the south bank of Pleasant Run creek. Named for Major General George B. McClellan, commanding general of United States forces in western Virginia, Camp McClellan would allow the 1,500 troops to get use to camp duties and to camp life. The troops were housed in a “tented field,” and, in the absence of natural shade, they cut brush and built arbors for shade under which they could take their meals.

While the regiments were in camp awaiting orders, some of the soldiers got into mischief. Drunkenness was a common complaint and with firearms near at hand, their misuse was a constant danger often with violent consequences. At Camp McClellan a volunteer shot another soldier while carelessly handling a revolver.

One June 4, 1861, the 8th Regiment marched back to Indianapolis to exchange its smooth-bore-muskets for rifle-muskets. While in the city, the regiment was presented “a piece of the secession flag that (Col.) Ellsworth tore down in Alexandria. The regiment swore that for that piece of rebellious rag they would capture three secession flags and bring them home as trophies….”

A week into camp, the 8th and 10th Regiments hosted a picnic at Camp McClellan on Saturday, June 8, 1861 for the regiments’ “ladies and friends.” The Indiana Central Railway ran a special train from Richmond, Indiana so people from the soldiers’ eastern Indiana communities in Wayne, Henry and Hancock counties could attend and trains left the Indianapolis Union depot every half hour for the camp so people from the city, for a round trip fare of ten cents, could also come to the picnic. Carriages and buggies crowded the National Road as many chose that form of transportation to go out to the picnic. Hundreds of men, women, and children converged on the camp grounds including children from the Indiana School for the Deaf and Dumb who were given free passage by the railroad. In a letter appearing in The Indianapolis Daily Journal following the picnic, the school children “were much gratified at seeing the military affairs and the parade.”

Numerous flags floated from high poles over the grounds giving the camp a “gay and lively appearance” as picnickers opened their baskets and spread their contents on the mess tables. Both regiments went on parade during the day displaying their drill proficiency. Also, Col. Benton, who had just returned from a meeting in Cincinnati with Gen. McClellan the previous evening, assured the regiments “that they were soon to have an honorable position in the field of battle.” Following the meal, the crowd was entertained with violin music and dancing that went on into the late afternoon. When the visitors left, the camp resumed its strict military order. The next day hundreds of visitors again came out to Camp McClellan to spend the day with the troops. The soldiers especially had a pleasant time since they had each received five dollars on their monthly pay so that they could buy various items from sutlers to meet their “comforts and necessities.”

With time running out on their three-month enlistments, the 8th and 10th Regiments struck their tents at Camp McClellan on the morning of Wednesday, June 19, 1861, and marched west on the National Road to the Indianapolis depot. Rumors that deployment orders had been received and “something’s up” had circulated in the city over the previous two days, especially when it was learned that the superintendent of the arsenal had received an order for the manufacture of a large amount of musket and rifle cartridges. The coming of the troops and their arrival in the city was heralded by music from the regimental bands and the clouds of dust stirred up by the tramping of 3,000 human feet along a dry dirt roadway. Great masses of civilians followed the soldiers in their march along the National Road into the city and “hundreds more” joined the troops in the march down Virginia Avenue to the depot of the Indianapolis & Cincinnati Railroad. Two special trains consisting of 13 freight and 28 passenger cars departed the depot carrying the regiments to join Gen. McClellan’s army in western Virginia to help in securing the loyal counties of Virginia and to protect the B & O Railroad.

-

Other News This Week

- 100 Years Ago This Week: March 28-April 3

- This Week’s Issue: March 28-April 3

- Andrew Merkley Named New Director of OPHS

- Indy’s Great Fires Part 2

- Franklin Twp. Historical Society Starts Expansion Campaign

- Capt. Gail Glaze: Mrs. Cowboy Bob

- “Visiting Mr. Green” at Epilogue April 3-13

- Franciscan Health Foundation Hosts Mobile Market on April 3 in Greenwood

- It’s My Business March 2025

- John Wesley Hardrick Exhibit at Indiana State Museum

Search Site for Articles