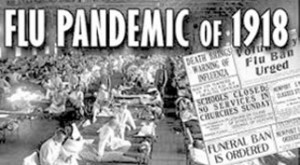

Along with the cool days of fall and as predictable as the changing leaves are the public service announcements reminding people to get their flu shots. Such was not the case a century ago when the great pandemic swept across the United States and the world, leaving many today with only misty memories of “my so-and-so family member died of the flu” as a reminder of that devastating health event along with the macabre children’s rhyme: “I had a little bird, its name was Enza; I opened up the window, and in-flu-Enza.”

News accounts of influenza, commonly known as Spanish Flu, being epidemic in the German army on the Western Front appeared in Indianapolis papers in early June 1918 and were quickly followed by reports of the disease in London and elsewhere. By August influenza was “taking whole nations in its grip,” and it made its appearance in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia during the last week of the month. The flu began in the far flung military camps where America’s sons were training in preparation for service overseas on the battlefields of France. Franklin D. Roosevelt, assistant secretary of the Navy, while sailing home from his visit to France and England, contracted Spanish influenza that developed into pneumonia. By the end of August, the disease had become an epidemic at military bases in Massachusetts and New York, and it quickly made its way west to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station at Chicago. On September 21, 1918 the influenza deaths of two Indiana sailors at the training station was reported. Sadly, additional Hoosier servicemen stationed at bases across the country would succumb to the disease in the days and weeks to come.

The pestilence made its appearance by September 25 in the Indianapolis area with the report of 125 cases of influenza among the members of the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce Training Detachment No. 2 stationed at the Indiana School for the Deaf and sixty cases of the disease at Fort Benjamin Harrison. Quarantines were established and in the city Mayor Charles W. Jewett directed Dr. Herman G. Morgan, secretary of the board of health, to require hotel lobbies, theaters, railway stations and street cars fumigated and cleaned. The mayor also directed the chief of police to see to the rigid enforcement of the ordinance against spitting on the sidewalks and in street cars. The last day of September saw four cases of influenza being reported among Indianapolis citizens.

While the contagion had grown to epidemic proportions among the soldiers at Fort Harrison and the military detachments within Indianapolis by the first of October, the “malady [was] of a mild form” with no deaths, yet. Local public health authorities were taking every precaution to keep the illness from spreading to the civilian population and encouraged the wearing of a gauze mask. However, despite the assurances to the citizenry that the influenza “is under control and will soon be overcome,” what began as a handful of new cases being recorded daily grew to 130 new cases being reported on Sunday, October 7; the toll for the week, 325 cases of influenza and four deaths, with six deaths from pneumonia.

Dr. Morgan issued a “sweeping order prohibiting public gatherings of five or more persons” to combat the influenza epidemic. Theaters, motion picture houses, and other places of amusement went dark, school and college classrooms stood empty, and the city pulpits were silent. Even the burial of the dead had to be in private. All meetings, except Liberty Loan committee meetings and the “necessary grouping of persons in business houses and manufacturing plants” were banned. To prevent the crowding of street cars during the morning and evening rush hours, the board of health ordered downtown retail stores to open at 9:45 a.m. and close at 6:15 p.m. thereby separating the travel times of department store employees and early shoppers from the office and factory workers. With 6,000 cases of influenza prevalent in forty-two counties outside of Marion County, the state board of health for the first time in Indiana history prohibited all public gatherings in an attempt “to check ‘flu’ spread” and required the posting of “QUARANTINE, INFLUENZA” cards on houses where the contagion was reported.

Day by day, new cases of influenza in Indianapolis among civilians steadily increased by the tens and then by the hundreds with a peak day of Thursday, October 10 reporting 425 new cases; sadly, the grim reaper was ever-present daily. No class, no ethnicity, no age, no profession was spared. Dr. Charles P. Emerson, dean of the Indiana University School of Medicine, observed “that in proportion to her population, Indiana is one of the states hardest hit by the influenza.” While doctors were stretched in treating victims of the scourge, there was a scarcity of nurses to provide continuing care. The Red Cross established a clearing house to register nurses and made a plea for women with some medical training to come forward. Indianapolis pharmaceutical firm Eli Lilly & Co offered a vaccine that wasn’t an “absolute immunization from influenza” but was effective in “staying pneumonia.” Patent medicines advertising treatments for respiratory illnesses added influenza to the list of complaints, and oranges and lemons were also considered palliative remedies for the disease. “The sprinkling of a little sulphur in each shoe every morning” was another suggested preventative measure.

By Halloween, reported cases of the flu had dropped sufficiently for the city board of health to lift the ban on public gatherings; “all normal activities” in Indianapolis resumed. The state-wide ban would be lifted a week later. The toll for the month: 6,129 influenza cases with 377 deaths among the city’s civilian population. The soldiers stationed around the city suffered 3,879 flu cases with 228 deaths. The Spanish Flu remained through November and December, continuing into the early months of 1919. From October 1 through the end of December 1918, 11,465 cases of influenza were reported in Indianapolis. More than 200,000 cases of the contagion were reported in Indiana, causing 8,993 deaths. Military authorities claimed that more soldiers died from the disease on the home front than were killed by German and Austrian bullets on the European fronts.

Today with the coming of autumn breezes we have brought out the flannel shirts and sweaters, and if you haven’t gotten a flu shot yet, do so. Don’t leave the window open to in-flu-Enza.