This column first appeared in the June 28, 2013 issue of the Weekly View.

The Major League All-Star game is just around the corner and once again network time usually devoted to regular season baseball games will be filled with baseball-themed movies like Major League, Field of Dreams, A League of Their Own, Eight Men Out and, of course, The Natural. But did you ever stop to think, is Robert Redford’s character in The Natural based on a real life player? Well, the answer is yes — and no.

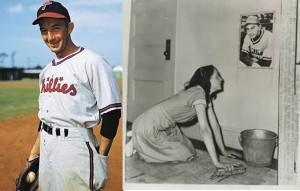

It would be more accurate to say that the film is based on an event, rather than an individual player. On June 14, 1949 Philadelphia Phillies “Whiz Kid” (and former Chicago Cub) first baseman Eddie Waitkus was shot by an obsessed fan named Ruth Ann Steinhagen in a Chicago hotel room. The comparison between Waitkus and the movie character pretty much ends there. But it is a helluva story.

Just a few years into the start of what seemed a very promising career, Waitkus was shot in the chest at the Edgewater Beach Hotel in Chicago. A 19-year-old typist at the time of the incident, shooter Steinhagen became infatuated with Eddie when he was a Cub and seeing him play every day fed her obsession. However, once he was traded to the Phillies, Ruth Ann’s sanity snapped when she realized that her “crush” would only be in Chicago 11 games that season.

Born two days before Christmas in 1929, Ruth was the daughter of immigrant parents from Berlin, Germany. Born Ruth Catherine Steinhagen, she adopted the middle name Ann at some point in her youth. While she never actually met Waitkus before she shot him, she created a ‘shrine’ to him inside her bedroom with hundreds of photographs and newspaper clippings — sometimes spreading them out and looking at them for hours, according to her mother. She would often set an empty place across from her at the dinner table reserved for Waitkus. She told her doctors after the incident, “I used to go to all the ball games to watch him. We used to wait for them to come out of the clubhouse after the game, and all the time I was watching I was building in my mind that idea of killing him.”

In 1948, Steinhagen’s family sent her to a psychiatrist, but her obsession didn’t diminish, even after Waitkus was traded to Philadelphia. After the shooting, police found extensive clippings in her suitcase and even pictures papering the ceiling of her bedroom at home. On June 14, 1949, the Phillies came to Chicago for a game against the Cubs. After the game, which she attended, Steinhagen sent Waitkus a handwritten note through a bellboy, inviting him to visit her in her 12th floor room in the Edgewater Beach Hotel where they were both registered.

Claiming to be Ruth Anne Burns, the note began: “Mr. Waitkus–It’s extremely important that I see you as soon as possible. We’re not acquainted, but I have something of importance to speak to you about. I think it would be to your advantage to let me explain to you.” After insisting that she was leaving the hotel the next day and stressing the urgency of the request, she concluded: “I realize this is a little out of the ordinary, but as I said, it’s rather important. Please, come soon. I won’t take up much of your time, I promise.”

According to Waitkus’ friend and roommate, Russ Meyer, Waitkus received the note, which was attached to the door of their 9th floor room after returning from dinner with Meyer’s family and fiancé past 11 p.m. Waitkus called the room but the woman would not discuss the details over the phone. The Sunday Gazette Mail said Waitkus knew some people named Burns. Waitkus’s son later speculated that his father may have “thought he had a hot honey on the line.” For whatever reason, he went to meet her in the room.

The details of what happened in the room are a little sketchy. According to the Associated Press report the day after the shooting, Steinhagen told police that as Waitkus entered the room, she greeted him by saying, “I have a surprise for you,” after which she retrieved a .22 rifle from the closet and shot him in the chest. Meyer said that Waitkus told him that when he entered the room, the woman claimed to be “Mary Brown.” He said that Waitkus claimed Steinhagen’s words after retrieving the gun from the closet were “If I can’t have you, nobody else can.” Another account claimed that Steinhagen said, “You’re not going to bother me anymore.” Waitkus, who later said he believed the woman was joking, stood his ground and was shot. He said he asked her, as she knelt beside his prone body with her hand on his, “Oh baby, what did you do that for?”

Steinhagen later told police that she had originally planned to stab Eddie, and use the gun to shoot herself, but changed her plans when Waitkus walked into the room and sat down. Steinhagen still intended to shoot herself, but evidently could not find another bullet. While Waitkus was lying on the floor bleeding from the chest, Steinhagen called down to the front desk of the hotel and told them “I just shot a man….” After the shooting, she went to wait for the authorities on the benches near the elevator, although she later claimed that she stayed with the wounded man and held his head in her lap until help arrived. The phone call, which brought quick medical attention as well as police, saved Waitkus’ life.

Steinhagen was arrested and then arraigned on June 30, 1949. Questioned about the shooting, she told police she did not know why she had done it, explaining that she wanted “to do something exciting in my life.” Strangely, when taken to Waitkus’ hospital room the day after the shooting, she told Eddie that she didn’t know for sure why she had done it. She told a psychiatrist before she went to court that “I didn’t want to be nervous all my life,” and explained to reporters that “the tension had been building up within me, and I thought killing someone would relieve it.” She said she had first seen Waitkus three years before, and that he reminded her “of everybody, especially my father.”

Steinhagen’s counsel presented a petition to the court saying that their client was “unable to cooperate with counsel in the defense of her cause” and did not “understand the nature of the charge against her.” The petition requested a sanity hearing. At the ensuing sanity hearing (which also occurred on June 30, 1949), Dr. William Haines, a court-appointed psychiatrist, testified that Steinhagen was suffering from “schizophrenia in an immature individual” and was insane. Chief Judge James McDermott of the Criminal Court of Cook County then directed the jury to find her insane, and ordered her committed to Kankakee State Hospital. The judge also struck “with leave to reinstate” the grand jury’s indictment of Steinhagen on a charge of assault with intent to commit murder, meaning that prosecutors could refile the charge if Steinhagen recovered her sanity.

Steinhagen never stood trial, but instead was confined to a mental institution until 1952, when she was declared cured and released. Waitkus did not press charges against Steinhagen after she was released, telling an assistant state’s attorney that he wanted to forget the incident. After her release, Steinhagen moved back home to live with her parents and her younger sister in her parents’ small apartment on Chicago’s north side. She shunned publicity in the ensuing decades, and remained a recluse for the rest of her life. In 1970, she and her family purchased a home in a crowded, racially mixed neighborhood on Chicago’s northwest side. She lived in the home with her parents and sister and, after their parents died in the early 1990s, continued to live there even after her sister died in 2007. She employed full-time caregivers in her final years.

She lived a quiet and secluded life, steadfastly maintaining her privacy, avoiding reporters, and refusing to comment publicly on her shooting of Waitkus. She never married and worked an office job for 35 years, and her neighbors and coworkers never knew of her place in infamy. Court records and routine background checks reveal no information about her career. On December 29, 2012, Steinhagen died in a Chicago hospital of a subdural hematoma that she suffered as a result of an accidental fall in her home. She was 83 years and six days old, and left no immediate survivors.

The bullet that struck Waitkus lodged in a lung, barely missed his heart, required four surgeries and prevented his return to baseball for the rest of that 1949 season. Eddie nearly died several times on the operating table before the bullet was successfully removed. The incident profoundly influenced Waitkus’ career and personal life as well; he was never the same player after the shooting. Eddie developed somewhat of a phobia worrying that others might not understand why he had visited Steinhagen’s room. He also, according to roommate Meyer, developed a drinking problem after the incident.

On August 19, 1949, the Phillies held “Eddie Waitkus Night” at Shibe Park and showered their wounded first baseman with gifts. Waitkus appeared at the stadium in uniform for the first time since he was shot in Chicago. Although the shooting left Waitkus knocking on death’s door, he was back in the Phillies’ Opening Day lineup the next year, going 3-for-5. After the 1950 season, Waitkus was named the Associated Press Comeback Player of the Year.

The Waitkus shooting is regarded as the inspiration for Bernard Malamud’s 1952 baseball book The Natural, which was made into a film by Barry Levinson in 1984. Other than the shooting, it’s hard to make a comparison between Eddie Waitkus and Roy Hobbs, the character played by Robert Redford in the film. In The Natural, Hobbs was shot as a teenage phenom before ever reaching the majors and the shooting kept him from reaching the big leagues until the age of 34, at which point he immediately started hitting like Babe Ruth with his miracle bat “Wonder Boy.” When shot, Waitkus was a 29-year-old veteran of both World War II and 448 major league games.

Miraculous comeback aside, Waitkus, who died in 1972, was no Hobbs at the bat. Though he was enjoying his finest season when he was shot, he had just one home run in 246 plate appearances, and when he retired in 1955 at age 35, he had just 24 home runs in 4,681 at bats. Waitkus hit for respectable averages (.304 in 1946, .306 in 1949 before the shooting, .285 for his career), but they were empty. He hit for little power and drew only an average number of walks. He did make a pair of All-Star teams and drew some low-ballot MVP votes in two seasons, but was by no means a Hall of Fame candidate.

Whether it was the seasons lost to World War II, his advancing age or the shooting, Eddie Waitkus never really lived up to the Roy Hobbs hype. Turns out that author Malamud built his iconic character around what was by far the most interesting thing about Waitkus’s career; the shooting. The similarities between fact and fiction end with the echo of that gunshot.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest books are “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View,” “Irvington Haunts. The Tour Guide,” and “The Mystery of the H.H. Holmes Collection.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.