In the past two columns I’ve introduced you to Osborn Oldroyd, king of all Lincoln collectors. Over the years, I have chased Oldroyd from Springfield, Illinois to Washington D.C. to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania and most recently to Marshalltown,Iowa. In Gettysburg, I purchased a collection of Oldroyd memorabilia assembled over two decades by a former Abraham Lincoln impersonator named Bill Ciampa.

The collection of over 300 items included photos, postcards, books, literature, brochures, business cards, certificates and even a paperweight. But the bulk of the assemblage consisted of letters written to Oldroyd spanning the time he spent living in the Lincoln family home in Springfield to his move to the “House Where Lincoln Died” across the street from Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.

Granted, the letters were a bit picked over by the time they landed in my lap. Gone were the letters from the big names associated with the life and death of Abraham Lincoln that Oldroyd quoted in his many books about our sixteenth President. There was no U.S. Grant, Andrew Johnson, Mary Lincoln, Winfield Hancock or George Meade, although Oldroyd was known to have corresponded with all of them. But there were a couple famous, albeit obscure, personalities from the Lincoln Era that remained. I recognized a letter from suffragette and women’s Temperance leader Frances Willard as well as another from T.M. Harris, a Brigadier General who served on the Lincoln Conspirators trial in Washington, D.C. Harris wrote the forward to one of Oldroyd’s books.

There was a fascinating letter from Ferdinand Petersen, son of the owner of the House where Lincoln died, who was present the night Lincoln was assassinated. The letter was written in October of 1913 by Ferdinand to Oldroyd in an effort to clear up several myths that had plagued his family for years about that tragic night. “It makes me tired as the youngest man living of the very few left who were there at the time…I own and still have the pillow cases on which President Abraham Lincoln died and I have mostly all of the pictures that were in the room at the time and…I do not wish to sell them to the Government either nor any relic I have…Someday I’ll hand them over to the government for preservation.” Ferdinand also makes it a point to dispel the rumor that the Petersen house was ever a rooming house. “It was a home.”

Another of the letters, dated Dec. 10, 1902, touched me personally because it was written by the sister of Louis Weichmann, the main government witness at the trial of the conspirators. Weichmann lived in Mrs. Surratt’s boarding house and many believe it was Weichmann’s testimony that got Mary Surratt hung. Weichmann moved to Anderson, Indiana after the trial and founded Anderson business college. He is buried in Anderson’s St. Francis cemetery in an unmarked grave. “Dear Sir-I am sending you a copy of Sundays Indianapolis Journal containing a confession of one of the conspirators of President Lincoln….With best regards from our family, I remain Sincerely yours, Mrs. C.O. Crowley Sister of the late L.J. Wiechmann.” Curiously, Mrs. Crowley misspelled her own maiden name in her letter.

There is an amusing letter dated April 9, 1906 from Teddy Roosevelt’s Secretary of the Treasury to Oldroyd: “It is requested that the flag in which J. Wilkes Booth caught his spur, and which was loaned to you for temporary use in the house in which President Lincoln died, be delivered to the bearer for return to the Treasury Department.” It’s easy to imagine Oldroyd’s dismay at the prospect of returning such an important artifact from his museum. More so, it intonates that this may not have been the first request for return.

However, it was the letters from common, everyday people that proved to be the most fascinating. The letters began in 1869 while Osborn was just an average autograph seeker and continued through to 1929 after Oldroyd sold his collection to the U.S. government and just months before he died in 1930. Several of the letters are from prospective customers wishing to obtain a copy of one of Oldroyd’s many books or souvenirs about Lincoln. Many of the letters were sent by visitors to his Lincoln museum. They extoll the hearty virtues of Oldroyd’s collection and his superior tour guide skills. (Funny, most of these are from women leading me to believe that Captain Oldroyd was an unashamed flirt.) Still more are from folks wishing to send Oldroyd some cherished family Lincoln memento for display in his museum. All of the letters offer a fascinating glimpse into the life of Osborn Oldroyd.

Two of the letters hail from the Hoosier state. One written in 1929 from L.N. Hines, President of Indiana State Teachers College (modern day ISU in Terre Haute): “I always remember my wonderful visit with you a year ago last February. I hope that I may be fortunate enough to come your way again before long.” and the other from a man in Larwill, Indiana written in 1926: “We have in our posession (sic) a campaign button of Lincoln & Hamlin. Would you care to have it among your other relics? Resp. Burton R. White”

The others, well, they’re from all over. They address Oldroyd variously as Colonel, Uncle, Cousin, Father, or Captain. A Boston lawyer writes: “I send you, herewith, a ticket of admission to the ‘Green Room’ (at the White House) on the occasion of President Lincoln’s funeral, April 19, 1865.” A York, Pennsylvania museum curator writes: “We have…a wooden short sword made out of the table that ‘Peanut Johnny’ used in front of Ford’s Theatre the night Lincoln was shot. It was ‘Johnny’ who held Booth’s horse.”

A Chicago businessman writes, “I want you to know how keenly I appreciate the kindness and courtesy which you showed me while in your museum. I count the hours spent there and with you, as the most pleasent (sic) and profitable ones of my weeks visit to our capitol.” A famous Washington D.C. female lawyer writes, “I have a friend who is in limited circumstances who has a very small lock of President Lincoln’s hair-which she wishes to dispose of-It occurs to me that you must know persons interested in Lincoln relics who might like to purchase this. It was given to Miss Gardner’s father Alexander Gardner, photographer to the Army of the Potomac by the undertaker who prepared Lincoln’s body for burial.”

Over the past several years, I feel like I’ve traveled in the footsteps of Oldroyd many times. I’ve experienced his highs and his lows. I’ve struggled alongside him as he labored to gain legitimacy for what Abraham Lincoln’s son Robert referred to as “Oldroyd’s Traps.” I agonized with his quest to sell his priceless collection to the United States Government (far below value) that took years to finalize. I think I understand him better now and, after three articles, you should too.

I think my feelings may best be summed up in a letter found in the collection that has become one of my favorites: “Washington, D.C. May 2, 1926. Dear Father Oldroyd: Accept hearty congratulations! I am glad I have lived to see your long years of effort rewarded, and your dream of sixty-three years come true. Very Sincerely, Kathie.” That letter sums it all up for me. Besides, my mother-in-law’s name is Kathie and I kinda like her too.

In the few years that have passed since I first wrote this series, a few things have changed. I have continued my pursuit of all things Oldroyd by picking up a few things here and there. I spent a weekend at the Lilly Library (on the campus of Indiana University in Bloomington) to examine a small group of letters and documents written by, or belonging to, Osborn Oldroyd. The library was created in the late 1950s by Josiah Kirby “Joe” Lilly Jr. (1893 – 1966) grandson of pharmaceutical magnate Eli Lilly. The Lilly Library, named in honor of the family, houses the university’s rare book and manuscript collections.

Lilly was a prolific collector of rare books and Indiana historical memorabilia. His collection included a First Folio of the works of William Shakespeare, a Gutenberg Bible, a double-elephant folio of John James Audubon’s Birds of America, the first printing of the American Declaration of Independence (the Dunlap Broadside), and a first edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s Tamerlane. Lilly’s gold coin collection is in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. In a November 26, 1954 letter to I.U. President Herman B. Wells, Lilly outlined his intention to donate the bulk of his collection to the university. IU announced the donation, which the New York Times estimated at over $5 million, on January 8, 1956. Lilly’s donation eventually totalled over 20,000 books and 17,000 manuscripts, including over 350 oil paintings and prints.

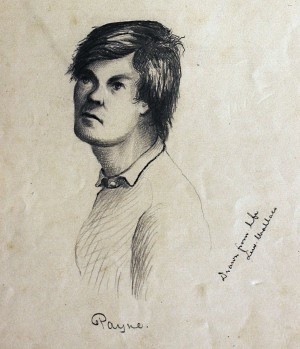

Included within that collection was a group of several dozen items that once belonged to Osborn Oldroyd himself. This included correspondence from Anderson’s Louis Weichmann to Oldroyd about shared information for books about Abraham Lincoln both men were simultaneously working on as well as photos and several handwritten eyewitness accounts of the assassination of President Lincoln. My personal favorite was a pencil drawing of Lincoln Conspirator Lewis Thornton Powell drawn by Crawfordsville, Indiana’s General Lew Wallace.

While most people recall General Wallace as the author of Ben Hur, many forget that he had other claims to fame, including nearly single-handedly saving Washington D.C. from capture by Rebel General Jubal Early’s troops at the Battle of Monocacy in 1864. He would later be appointed Governor of the New Mexico territory during Billy the Kid’s exploits and also served as a member of the Lincoln assassination conspirator’s trials. General Wallace made the drawing of Powell during the trial while sitting just a few feet away from the man who nearly killed Secretary of State William Seward. Powell would be hanged for his crime. No doubt this single item is the reason these particular Oldroyd items ended up at the Lilly Library.

What I came away from, after my springtime visit to IU’s Lilly Library, was an even deeper understanding of the passion that must have driven Osborn Oldroyd’s pursuit of Lincoln memorabilia. It became easy to understand the euphoria that surely overcame Oldroyd as he received, opened and read these personal accounts written by people connected to Mr. Lincoln. Viewing these priceless relics also reinforced the value of Osborn Oldroyd’s obsession. For without them, precious details and specific memories of historic events would have been lost forever. And thanks to Mr. Lilly, these particular objects are henceforth and forever available for viewing by all Hoosiers at the Lilly Library in B-town. Little did I know that this springtime visit to my alma mater was just the beginning of a journey that would occupy the next month of my life.

Next week: Part 4 of “Osborn Oldroyd-Keeper of the Lincoln Flame.”

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest book is “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.