Last week, I told you about a recent study that found one third of American men have not seen a doctor in over a year. What’s even more astoundingly is that in the last five years, the number of men who have not been to the doctor has reached well over 8 million. Surprisingly every year, males make over 100 million fewer trips to the doctor than women. A 1990 study by the American Medical Association showed that most men don’t go see a doctor for reasons that include denial, masculinity, and fear.

I shared with you the story of Walt Disney’s death, caused by lung cancer diagnosed only because Walt was at the doctor complaining of neck and back pain that he believed was a result of an old polo injury — a scenario that is more common than you might think. In this article we’ll look at another premature death that might have also been prevented by proper treatment and early diagnosis.

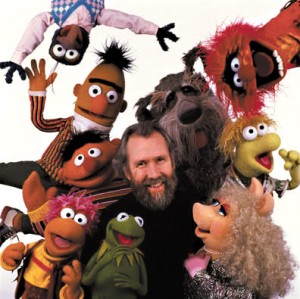

Jim Henson, creator of the Muppets and one of the visionaries behind “Sesame Street,” died unexpectedly of pneumonia on May 16, 1990. On May 4, 1990, Henson made an appearance on The Arsenio Hall Show despite suffering from what he told friends were sudden, flu-like symptoms. It would be one of Henson’s last television appearances. At the time, he told his publicist that he was tired and had a sore throat, but felt that it would go away.

A week later Henson traveled to Ahoskie, North Carolina, with his daughter Cheryl to visit his father and stepmother. The next day, May 13th, feeling tired and sick, Jim consulted a local physician, who could find no evidence of pneumonia by physical examination and prescribed no treatment except aspirin. Henson returned to New York on an earlier flight and canceled a Muppet recording session scheduled for May 14.

Henson’s wife Jane, from whom he was separated, came to visit and sat with him talking throughout the evening. By 2 a.m. on May 15, he was having trouble breathing and began coughing up blood. He joked to Jane that he might be dying, but insisted that he did not want to go to the hospital. She later told People magazine that it was likely due to his desire not to make a fuss or be a bother to people.

At 4 a.m., he finally agreed to go to New York Hospital. By the time he was admitted at 4:58 a.m., he could no longer breathe on his own and had abscesses (cavities containing pus, surrounded by inflamed tissue, formed as a result of infection) in his lungs. He was placed on a ventilator to help him breathe, but his condition quickly deteriorated into septic shock despite aggressive treatment with multiple antibiotics. At 1:21 a.m. on May 16, 1990, 20 hours and 23 minutes after being admitted, Henson died at New York Hospital from organ failure at the age of 53.

The cause of death was first reported as streptococcus pneumonia, a bacterial infection. Henson died of organ failure due to a severe form of the infection that causes strep throat, scarlet fever, and rheumatic fever.

Two separate memorial services were held for Henson, one in New York City at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine and one in London at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Henson’s wishes were honored and no one in attendance at either service wore black. A Dixieland jazz band finished the service by performing “When The Saints Go Marching In.” Harry Belafonte sang “Turn the World Around,” a song he had debuted on The Muppet Show, as each member of the congregation waved, with a puppeteer’s rod, an individual, brightly-colored foam butterfly. Later, Big Bird (performed by Caroll Spinney) walked out onto the stage and sang Kermit the Frog’s signature song, “Bein’ Green.”

In the final minutes of the two-and-a-half hour service, six of the core Muppet performers sang, in their characters’ voices, a medley of Jim Henson’s favorite songs, culminating in a performance of “Just One Person” that began with Richard Hunt singing alone, as Scooter. “As each verse progressed,” Henson employee Chris Barry recalled, “each Muppeteer joined in with their own Muppets until the stage was filled with all the Muppet performers and their beloved characters.” The funeral was later described by LIFE magazine as “an epic and almost unbearably moving event.” The touching closing scene was recreated for the 1990 television special “The Muppets Celebrate Jim Henson.”

Henson was cremated at Ferncliff Cemetery just north of Manhattan, the same cemetery where John Lennon and Nelson Rockefeller were cremated. His ashes were scattered at his ranch in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Henson’s sudden death understandably caused an outpouring of public and professional affection resulting in numerous tributes and dedications in his memory. Henson’s companies, which are now run by his children, continue to produce films and television shows.

As with the death of Walt Disney a quarter century before, the public was shocked by Jim Henson’s passing. After all, Peter Pan isn’t supposed to die. True, like Disney’s mastery of animation before him, Jim Henson’s master of Muppetry never seemed of this earth. A towering 6’3”, Henson was lean and muscular with well defined arms and strong legs as a result of years of physical puppetry and appeared to be in perfect health despite the beard that made him look like Santa Claus. He was a gentle giant who’s tenderness in art, business, and private life enveloped all who came in contact with Jim or his magical world.

Henson was at the pinnacle of his career when he died. Jim’s PBS award-winning Sesame Street was seen in 80 countries. The Muppet Show, which aired in the U.S. from 1976 to 1981, had made his creations world famous. And, months before his death, Henson had agreed to sell Henson Associates to Walt Disney Co. for an amount rumored to be close to $200 million. Not bad for a man who started his career on a Washington, D.C. kiddie show and who once said, ”Puppetry is a good way of hiding.”

Ironically, Jim’s easy going “ah shucks” demeanor may have contributed to his death. The weekend before, Henson simply thought he was fighting a common cold. His daughter Cheryl’s recalled her father saying, ”I’m just tired” but she insisted he go to the doctor when he said “Hi ho, Kermit the Frog here.” Although this was a line uttered countless times by her father while performing, it was very unlike him to make the comment out of the blue. By Monday night, his organs were already shutting down. All day Tuesday, family and friends kept somber vigil. By Wedneday morning, after two cardiac arrests, Henson’s heart finally stopped.

Soon, after the grief subsided, the question arose, ”What will happen now?” To which Disney answered, “Nothing” by pulling the plug on the deal by saying, in effect, that Jim Henson was his company. Henson’s son Brian sued the Disney Corporation and ultimately the case was settled out of court. Ironic that these two men connected by similar visions, similar imaginations and similar demises would meet posthumously in court through their namesake companies. Even more ironic is that 14 years later, in 2004, the Disney company would buy Henson’s company from his heirs for a lot more money than Jim originally shook on.

Just as Walt Disney’s 1966 death by cancer contributed to the debate in America on smoking, Jim Henson’s death from pneumonia caused many Americans to believe that bacterial infections could no longer be killed by antibiotics and vaccines that worked reliably in the past. Perhaps humans were developing an immunity to these drugs from overuse.

Doctors were quick to point out that antibiotics are effective as lifesavers only when given in time. These drugs cannot always be relied on to be a last-minute salvation, particularly if the microbes have gotten the upper hand by spreading through the body. And contrary to widespread belief, pneumonia never disappeared as a major killer after the introduction of antibiotics. It remains the most common cause of death from infections and is the sixth leading killer of Americans.

We live in a sea of bacteria, fungi and viruses that are invisible to the naked eye. Many microbes are harmless and some are essential to life while still others are potentially dangerous. Of an estimated 500 infectious diseases, some 200 are untreatable. The relationship between people and microbes has many questions. Why one individual can be overwhelmed by certain dangerous microbes while another infected by the same microbe becomes a symptomless carrier remains a puzzle. (Remember Typhoid Mary?) Not to mention questions about the timing of an infection; why would someone fall ill with pneumonia suddenly when, like other infections, it is ubiquitous and constantly spread?

Among the unanswered questions about Mr. Henson’s death are: why he became infected with the streptococcal bacteria when he did; why his immune defenses failed to check the rapid advance of the microbes; and why, among the scores of microbes that cause pneumonia, was it the streptococcus that struck him? Physicians have a very simple way to detect pneumonia on routine examinations, they place the fingers of one hand over a rib and thump that hand with a finger from the other hand and listen for a resonant sound. A dull sound might indicate the presence of pneumonia in the lungs.

The physician also listens through a stethoscope to the flow of air as a patient takes deep breaths. Not to mention, pneumonias caused by viruses often show up on chest X-rays before even infectious disease experts can detect it with their fingers and stethoscopes.

Twenty-six years have passed since Muppets mastermind Jim Henson passed away and 51 years since Walt Disney left us. The sudden deaths of these men who brought immeasurable joy to children and adults alike shocked fans around the world. In the decades since their earthly exits, their creations continue to dance and sing and their legacies promise to live on for generations to come.

The main point of these articles is that both of these great men’s demise might have easily been prevented if they’d only seen a doctor on a regular basis. While their creative loss is obvious and the questions of all the lost cartoons, songs, jokes, and characters will never be answered, this same lesson can be applied to all my readers. See a doctor on a regular basis. Don’t ignore any warning signs. Don’t be stubborn by shrugging off the aches and pains of life. Contrary to the advice we all grew up with, don’t shake it off. Take care of yourself for your friends, your family, your loved ones. Most of all, make Walt Disney and Jim Henson smile from the heavens and do it for yourself.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest book is “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.