By now (assuming you’ve read parts 1 and 2 of this series) you know that a visit to the Big House in Macon, Georgia should be high on your bucket list. The Big House tells the story of the Allman Brothers Band during the years 1970 to 1973 when it served as home base for the band that defined Southern Rock. Although filled with light, music, energy and good times, the house had its share of tragedy and sorrow, too.

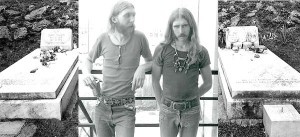

But to understand the band, you must face the music by taking a trip to nearby Rose Hill Cemetery. The cemetery, opened in 1840, was designed for the express purpose of being a place to visit and as a gathering place for the people of Macon. It was a place where the bandmates gathered in the lean years before they became a household name, back when they all lived in a two-room, $50-a-month apartment. It was a secluded, quiet place where the band could go alone or together to talk about music or dream about the future while surrounded by the past. The cemetery was pictured on album covers and mentioned in songs.

By the summer of 1971, the Allman Brothers Band were financially secure and critically successful. The rigors of the road had driven many in the band towards heroin addiction. By autumn of that year, Duane Allman and Berry Oakley, along with ABB roadies Robert Payne and Joseph “Red Dog” Campbell, were hopelessly hooked on smack. By October, the quartet had checked themselves into the Linwood-Bryant Hospital for rehabilitation. As Halloween approached, the four friends were on the road to recovery.

On October 29th, 1971, Duane popped in to the Big House to wish Berry’s wife, Linda, a happy birthday. Duane came in with a big bouquet of flowers for the party. Linda recalled that everyone was busy carving pumpkins for Halloween and Duane said, “Let me do the eyes, the nose and the mouth.” He left the house on his motorcycle and never returned.

At about 5:45 p.m., Allman was riding his Harley Davidson Sportster at a high speed towards the intersection of Hillcrest Avenue and Bartlett Street alongside a flatbed truck carrying a lumber crane heading in the same direction. As the truck turned into the lumberyard, Duane adjusted his course to avoid it but the truck inexplicably stopped, forcing Allman to swerve his Sportster’ overstock front fork modified bike to avoid a collision. Duane was now past the point of no return and he struck either the back of the truck or the “headache” ball on the lumber crane and was immediately thrown from the motorcycle. As Allman skidded helplessly down the road, in a freak accident-within-an-accident, the motorcycle bounced high in the air and landed on top of Duane, pinning its rider underneath for another 90 feet, hopelessly crushing his internal organs.

Despite devastating injuries, Duane, who was wearing a helmet, thought for a moment that it was just a severe case of road rash that could be shaken off. Although there was a lot of blood on the scene, Duane initially thought the bike (with its bent front forks, trashed front tire, and handlebar damage) took a worse beating than he did. Duane’s girlfriend Dixie Meadows and Berry Oakley’s sister Candy had been following him from some distance behind and did not witness the accident. They rushed to Duane’s side and stayed with him until an ambulance arrived. Paramedics said that Duane ceased breathing twice in the ambulance but was revived each time by mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. He was alive when he arrived at the Macon Medical Center, but died after three hours of emergency surgery from massive internal injuries. He was only 24 years old.

Dr. Charles Burden, the attending surgeon, said afterwards that any one of the injuries Duane sustained — a collapsed chest, a ruptured coronary artery and a severely damaged liver — could have caused death, but that the combination of injuries sealed his fate from the outset. Rock Candy tour guide Rex Dooley added, “Berry Oakley was riding his motorcycle a short distance behind Duane that day, But Berry wasn’t as good a rider as Duane and he missed the turn and took the long way around while Duane took the shortcut.”

The news of Duane’s death left his friends, family, and the entire music community in a state of shock and left a gaping hole in the middle of the ABB line-up. The band pledged to carry on, pulling it together quickly enough to play at Duane’s funeral in Macon’s Memorial Chapel. The culmination came when all joined to sing “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?”, a popular Christian Hymn that was a favorite of the band. After Duane’s death, the band held a meeting on their future; it was clear all wanted to continue, and after a short period, the band returned to the road.

The band returned to Miami in December to complete work on their third studio album, “Eat a Peach,” dedicated to Duane. The album name came from something Duane said in an interview shortly before he died. When asked what he was doing to help the revolution, Duane replied, “There ain’t no revolution, it’s evolution, but every time I’m in Georgia I eat a peach for peace.” Released in February 1972, “Eat a Peach” was the band’s second hit album, shipping gold and peaking at number four on Billboard’s Top 200 Pop Albums chart.

Bassist Berry Oakley tried hard to keep it together, but something died in him with Duane’s death. He told Linda that the hellhounds were on his tail. He began having nightmares and was drawn more and more to the dark blues of Robert Johnson and Elmore James. Oakley was visibly suffering from the death of his friend: he drank and consumed drugs to excess, and although always thin in stature, he was losing weight rapidly. According to friends and family, he appeared to have lost “all hope, his heart, his drive, his ambition, and his direction” following Duane’s death. “Everything Berry had envisioned for everybody, including the crew, the women and children, was shattered on the day Duane died, and he didn’t care after that,” said ABB roadie Kim Payne. Oakley repeatedly wished to “get high, be high, and stay high,” causing quiet concern from all those around him.

In October of 1972, a year after Duane’s death, the band recorded their best-selling hit “Ramblin’ Man.” In a 2014 interview, the song’s writer, Dickey Betts, recalled, “I wrote ‘Ramblin’ Man’ in Berry Oakley’s kitchen at the Big House at about four in the morning. Everyone had gone to bed but I was sitting up.” Ironically, it was one of bassist Berry Oakley’s last studio performances with the band.

Two weeks later, on November 11, 1972, Berry Oakley, slightly inebriated and overjoyed and looking forward to a jam session later that night, slammed his ’67 Triumph motorcycle into the side of a Macon city bus. Oakley was rounding a sharp right curve on Napier Avenue at Inverness when he crossed the center line and collided at an angle with the bus. After striking the front and bouncing off the back of the bus, Oakley was thrown from his bike, just as Duane Allman had been, and struck his head. The accident occurred only three blocks from the site of Duane’s fatal crash, a year and two weeks before. He was thrown 20 yards from the bike. Initially, Oakley said he was okay after the accident, declined medical treatment, and caught a ride home. Once back at the Big House, over the next three hours he gradually grew more and more delirious. He was rushed to the hospital and died of cerebral swelling caused by a fractured skull.

Like Duane before him, attending doctors stated that even if Oakley had gone straight to the hospital from the scene of the accident, he would not have survived his injury. Eerily, both men died at the age of 24. Other eerie similarities exist in these deaths of brothers-from-other-mothers: Both men left from the Big House, both died on motorcycles, both crashed into truck-like vehicles and both men are buried side-by-side at Rose Hill Cemetery — the same cemetery that they spent much time in together during their younger days.

Duane and Berry were integral to the story of the Big House. I could not help but wonder if they weren’t still there. I asked Maggie Johnson if there were any ghost stories to tell. She made it clear that the only thing that has ever really “spooked” her was when singer-songwriter Jason Mraz showed up for one of her tours. “I really couldn’t concentrate,” she said. She then perked up and answered, “Yes, we have a few spooky things that have happened here.” She relayed how the previous owners swore that the ghost of a small child resides within the Big House. This ghostly little girl was seen in shadow form on several occasions, and on more then one instance the former owner swears the childlike spectre tried to push her down the stairs.

Rex Dooley stated that those same owners, who lived in the Big House for 14 years, often saw the ghosts of Duane Allman and Berry Oakley roaming the halls and on the stairways of the old house. Maggie continued on by saying that sometimes late at night when she is all alone in the house at work on the third floor ballroom that now contains the staff offices, she can hear random music, guitars in particular, wafting up from the floors below.

Maggie began to tell tales on Richard, saying that he has reported strange sounds coming from the walkie talkies (once used by staff to communicate between floors) at times when the house is empty and the devices are securely plugged into their chargers. She went even further by saying that Richard was once alone in the house locking up for the night when he heard footsteps coming from the third floor ballroom. “He packed up and left” Maggie said with a giggle. Did I mention that Richard Brent looks like a guy who could wrestle a bear… and win?

Lastly, Maggie recalled a time when a securely framed picture of Duane perched on a shelf behind a large locked glass door protecting the closet in his former bedroom fell off and crashed to the floor. Upon further examination, Maggie discovered the picture had scratched the body of Duane’s first Gibson Les Paul Jr. guitar displayed beneath it. Maggie pointed out that this is the only replica guitar in the house. But there is a very good reason for that: the original is on display at the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland. That disclosure is perfectly acceptable and aptly explained to all of us, but maybe Duane Allman wants his old guitar back.

So the next time your heading down for a Florida vacation, or a business trip to Nashville, Chatanooga or Atlanta, do yourself a favor. Make a trip to the Big House at 2321 Vineville Avenue in Macon, Georgia. It’ll be the best ten bucks you’ll ever spend!

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest books are “Bumps in the Night.Stories from the Weekly View” and “Irvington Haunts. The Tour Guide.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.