On November 2, the Indiana State Museum gave the media an advance look at one of the first phases of a five-phase, $18-million transformation of the museum. Reporters, camera operators and columnists gathered in the museum’s cafeteria to await our welcome and opening introductions. Through the cafeteria’s windows could be seen blue and yellow balloons, tethered to the ceiling, dangling in front of a three-story, gold-faced sculpture of the word “Indiana.” Below it, tables were set for the stakeholder’s preview, at which the president and CEO of the American Alliance of Museums, Laura L. Lott, was to speak. In the cafeteria, the media group was divided between Beth Van Why, Associate Vice President of Exhibitions, and Susannah Koerber, Senior Vice President of Collections and Interpretation. Koerber took her media group through the three new exhibits: Contested Territory, 19th State and Natural Regions.

Koerber pointed out the flow of the three exhibits, from Contested Territory — which has an audio and video representation of the speech of the native Miami with English translations — through 19th State and into the Natural Regions. Koerber was joined by some of the curators of the exhibits — Dale Ogden, Todd Stockwell and Mary Jane Teeters-Eichacker — as she pointed out features of the exhibits that demonstrated that the museum was determined not want to shy away from the more difficult things (about) Indiana history, including the treatment of Native Americans. She noted that most of Indiana was treaty land. As Contested Territory flowed into 19th State, the implements and living quarters of pioneer life are represented, including the “round-log” type of cabin that the young Abe Lincoln might have lived in during his time in Indiana.

In 19th State, we learned that 60,000 citizens comprised the required threshold for statehood, which was granted to Indiana in December, 1816. Koerber emphasized both the chronological and “emotional rhythm” of the exhibits were augmented with additional items of interest that could be changed out to add context and interest. One of those items was the original Treaty of Greenville, signed by Native American tribes, including the Miami, in Ohio. When the United States forced the Miami to give up their last reservation in Ohio, many of them settled in Indiana.

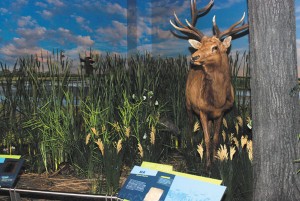

The tour ended with Natural Regions, an exhibit highlighting the state of the state of Indiana before man chopped down the trees and cleared the grasslands. When a tour member expressed surprise at the size of a represented sycamore tree (“There were trees that big?”), curator Damon Lowe assured the group that the 30-foot wide tree was smaller than the recorded 50-foot circumference of some the early sycamores of the state. Lowe pointed out that Central Indiana is the region of the Tipton Hill Plain, with black bear and cave crickets and bobcats; the Shawnee Hills region is in Southern Indiana and the Kankakee Marsh described the northwest Indiana region. The magnificent taxidermy of all the Natural Regions was on clear display with a huge elk and birds in flight over marsh grasses. Koerber’s passionate advocacy for the museum’s more immersive (and) interactive experience for visitors was demonstrated by the marshy footing in the Kankakee Plain exhibit, and the realistic sound of insects buzzing in a visitor’s ear. There is also a Soundscape room that has representative audio recordings of what might have been the sounds of Indiana from pre-European settlement through early settlement and into the early industrial period.

The three new galleries opened to the public on November 12, bright additions to the museum’s offerings and intriguing precursors for the museum’s plans through 2019, in time for the museum’s 150th anniversary.