Herman Webster Mudgett, better known under the name of Dr. Henry Howard Holmes or colloquially as H.H. Holmes, was America’s first serial killer. In Chicago, Holmes opened a hotel in Chicago (just in time for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition) designed and built specifically with murder in mind. While he confessed to 27 murders, his actual body count could be as high as 200. After Holmes’ capture, conviction and execution, a strange cult of superstition began that would soon become known as the Curse of H.H. Holmes.

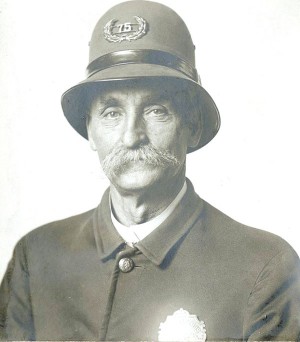

As detailed in Parts 1 and 2 of this series, Holmes committed one of his last murders right here in Irvington. By the summer of 1895, Holmes was being chased by a dogged Pinkerton Detective Agent named Frank S. Geyer. He was assisted in his pursuit by Indianapolis police officer David S. Richards, an officer first appointed in 1872. The Metropolitan Police Force was reorganized on April 14, 1883 into a new police force totaling 59 men. David S. Richards was a charter member of that very first Indianapolis Police Department.

Detective Geyer arrived at Indianapolis Police Department headquarters on July 25, 1895. He asked for a member of the detective squad to assist in his search and was assigned Detective David S. Richards. A 23-year veteran of the department and local legend, Richards was once nearly killed in a gun battle with the murderous Modoc gang in the Fall Creek bottoms (near Fall Creek Parkway and Capitol Avenue). The Modoc gang terrorized Indianapolis during the 1870s, committing over 200 robberies. The gang hid out in the “bottoms” area of Fall Creek near the Tennessee Street bridge, site of the original St. Vincent’s Hospital and now home to Ivy Tech Community College.

At 10 a.m. on the morning of on July 2, 1879, Patrolmen David S. Richards and Jeptha W. Bradley of the Indianapolis Metropolitan force came upon the suspects at the Fall Creek bottoms area. Almost immediately, Patrolman Bradley was clubbed unconscious with a heavy object. At least 20 shots were fired during a brief but frantic gunfight. Richards was shot in the melee but not before he returned fire, hitting Modoc gang member James “Jack” Carrigan in the head and left shoulder. The Modoc gang carried off their wounded compadre through the rain-swollen waters of the White River at Cold Springs not far from the present day site of the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

The two wounded officers were taken to the Surgical Institute and word of their injuries traveled quickly to police headquarters. Richards had taken a bullet to the top of his head and his face was covered in blood. For a moment his wounds were thought to be mortal and in the frenzied first moments after he was discovered Richards was reported DOA to local newspapers. A physician took a closer look and discovered that the officer was still very much alive. After regaining consciousness, it was discovered that Richards was shot three times: one bullet lodging in his left foot, another shearing off his left ear lobe and the third creasing his scalp. It was later discovered that no fewer than four bullet holes had passed through his uniform coat missing him completely.

According to newspaper accounts of the day, when Chief of Police Al Travis arrived at the wounded officer’s bedside, Richards stuck his hand out and said, “Chief, I’d a got my man if it hadn’t been for ‘Modoc’ shooting me.” “I know you would have, Dave”, the chief responded. The next day IPD Captain R.C. Williamson and Patrolman James R. Shea searched the area south of the Belt Railroad junction near Brightwood and came upon two members of the Modoc gang. Barney Moran and John “Jack” Murphy were found sound asleep. Both men were armed; Murphy with Patrolman Jeptha Bradley’s weapon at his side.

Indianapolis Police tracked “Modoc” to Marseilles, Illinois, west of Chicago. They captured him August 7, 1879 and he was charged with shooting Patrolman Richards in the leg. On September 24, 1879 The jury trial resulted in a guilty verdict. The judge fined Modoc a mere $50 and sentenced him to only six months in the county jail for “assault and battery with intent to get away.” Modoc was pardoned before the six months was served out.

Patrolman Bradley’s wounds resulted in permanent hearing loss which caused him to leave the ranks of the IPD. Jeptha W. Bradley became a printer after leaving the police force. He died April 20, 1894 at the age of 63, six months before H.H. Holmes came to Irvington. As for Richards, the wounds received in that gun fight would plague him the rest of his life and echo through the annals of IPD history all the way up to 2015. Despite the severity of his injuries, Patrolman Richards returned to duty in November 1879.

Richards had been elevated to the post of detective by the time he was assigned to assist Pinkerton agent Geyer in the hunt for H.H. Holmes. After meeting Geyer on the afternoon of July 23, 1895, the two detectives began their search. They visited every real estate office in and around Indianapolis over the next 30 days to no avail. On the evening of August 26th, while sitting in the lobby of their hotel, Geyer asked Richards if there were any small towns outside of Indianapolis they had yet to check. Richards responded, “Well, there’s two, yet we haven’t investigated, Irvington and Maywood.” The detectives traveled to Irvington the next day, the details of that surprising visit were recounted in Geyer’s own words in part one of this series.

Detective Sergeant David S. Richards of the Indianapolis Police Department retired in January of 1912 after 39 years and nine months of exemplary service. He was just four months shy of putting an eighth five year stripe on his uniform, something no other officer had ever done, but the pain of his injuries suffered 33 years before deprived him of that singular honor. He had served more years on the department than any other man at that time. By now, the rumors of a curse upon all those involved in the Holmes crime and prosecution were well known and often the subject of follow-up newspaper columns.

When another member of the jury committed suicide in March of 1912, The Indianapolis News contacted Detective Richards for comment about the Holmes’ curse. Richards, now retired from the Indianapolis Police Department, had become somewhat of a legend in the city for the role he played in solving the murder of little Howard Pitezel. He told the reporter, “I have to laugh at that story every time I hear it.” Meantime, the curse trudged on.

In early 1914, the Chicago Tribune reported the death of Pat Quinlan, the former caretaker of the Murder Castle, in an article titled “The mysteries of Holmes’ Castle.” Quinlan had spent the past two decades plagued by hallucinations of the awful experiences he endured during his employment by Holmes. For a time after the crime’s discovery, Quinlan continued to live in the doomed hotel. Quinlan repeatedly told friends and other interested parties that the Castle was haunted by the ghosts of Holmes’ many victims. These ghosts, he claimed, would haunt him in his sleep by roaming the halls and tapping on the windows of the Castle. He claimed that the spirits followed him even after he moved back to a farmhouse in his Portland, Michigan hometown. By the spring of 1914, Pat Quinlan was a broken man.

On March 7, 1914 Patrick Quinlan picked up a slip of paper and scribbled a note reading, “I could not sleep.” He then quietly committed suicide by drinking from a bottle of pesticide whose active ingredient was deadly strychnine. Pat’s facial muscles stretched tight and a peculiar metallic taste flooded his mouth. His calf muscles began to stiffen and convulse, his toes curled up under his feet and as his head thrashed back-and-forth, blinding flashes of light darted across his eyes. His body went ice cold as he finally drifted off into that final sleep. Witnesses claimed that in death, he looked as though he had been carried there by the ghosts of the slain women of the Castle he helped to build. Pat Quinlan had killed himself and most blamed the curse for his demise.

Detective David S. Richards, who had laughed off the notion of a curse ten years before, began to experience searing pain in his left foot. Richards, a tough old bird, understated the pain by telling friends, “its just a twinge now and then.” Richards, seeking relief from the agony of his festering, open wound, finally visited the hospital on New Years Day of 1922. There, doctors amputated his gangrenous foot caused by that unhealed bullet wound suffered 43 years earlier. Two days later, on January 3, 1922, he passed away at Eastman Hospital (a stone’s throw from where Lucas Oil Stadium stands today) at the age of 75. Richards had lived In Indianapolis fifty-two years. However, his story did not end there.

Ninety three years later, in 2015, research by IMPD Police Sergeant Jo Ann Moore determined that Richards’ death was a direct result of that bullet from the Modoc Gang shootout in Foggy Bottoms. Detective David S. Richards death was reclassified and determined as a death in the line of duty. David S. Richards name was added to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund (NLEOMF) roll of honor in Washington, D.C.

The research, discovery and recognition of Detective Richards was due solely to the dedicated work of Sergeant Jo Ann Moore. Sgt Moore, a departmental historian, carefully and methodically investigated Richard’s career using newspaper files and department records. Sgt. Moore has been a genealogist for 30 years and utilized skills honed in that hobby to ensure that her fellow officers and their families are never forgotten, even those who died a century ago. She has a personal stake in this important endeavor. For you see, Sgt. Jo Ann Moore is IPD royalty. She is a Gold Star mother. Her son, IMPD Officer David Moore, was the first officer killed in the line of duty after the IPD and the Marion County Sheriff’s Department merged in 2007. With the help of dedicated officers like Sgt. Moore, the curse of H.H. Holmes doesn’t stand a chance.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest book is “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.