We all do it, some more than others I suppose, but we all do it: Daydream. Winning the lottery, scoring a hole-in-one, dating a movie star or maybe embarking on an exotic vacation, we all daydream. For me, I daydream about history. Lately, I’ve been daydreaming about the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair. Recently, the 50th anniversary of the fair’s final day passed and I guess it made me wistful for what once was. I know, there are many more important historical waymarks to daydream about, but the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair just sounds like fun to me.

The fair at the Flushing Meadows Park in Queens, New York was held for two six-month seasons — April 22 to October 18, 1964 and April 21 to October 17, 1965 — for a total of 260 days. The New York World’s Fair was not sanctioned by the official Bureau of International Expositions (or BIE) and remains as the only such fair to ever do so. In order to maximize the fair’s profits, fair organizers decided to collect heavy rents from companies choosing to build and open pavilions at the fair. The BIE, which regulated World’s Fairs the way the International Olympic Committee regulates the Olympics, had a rule that prohibited this. Hence, the BIE retaliated by urging all its member nations to boycott the fair. Several important nations did boycott the fair, including the British Commonwealth, the USSR and the entire Soviet bloc.

Undeterred, the fair went on as scheduled and became the largest World’s Fair to ever be held in the United States. The fairgrounds occupied the same footprint as the 1939-40 New York World’s Fair, which prior to 1939 was known as the Corona Ash Dumps, an area filled with ashes from coal-burning furnaces, horse manure and garbage. The region was characterized as “a valley of ashes” in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. The ambitious 25th anniversary effort featured 140 pavilions spread over 646 acres (nearly one square mile). Among the many attractions and pavilions were four designed by The Walt Disney Company.

Can’t get wistful about the fair? How about this: In 1964-65, the average cost of new house was $13,050; average income per year $6,000; average monthly rent $115.00; a new car cost $3,500; gas was 30 cents per gallon; a loaf of bread 21 cents; U.S. Postage Stamps were 5 cents. For proper perspective, when the fair opened an era of lost illusions had begun. The John F. Kennedy assassination was still very fresh in the American psyche. The Civil Rights Act was stalled in Congress, the Vietnam conflict was escalating and the Beatles landing in America had set off a youthquake.

The fair’s theme was “Peace Through Understanding,” dedicated to “Man’s Achievement on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe.” That theme was symbolized by a towering 12-story high, stainless-steel model of the earth called the Unisphere (sponsored by U.S. Steel). Admission for adults (13 and older) was $2 in 1964 (about $15 today) but jumped to $2.50 in 1965, and $1 for children (2–12) both years. The fair’s legacy is as a showcase of mid-20th-century American pop culture, technology and the Space Age. More than 51 million people attended the fair.

The 1964/1965 Fair was conceived by a group of New York businessmen who remembered their childhood experiences at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. The businessmen ran the fair, well, like a business. It was populated by major American corporations and geared heavily towards the American consumer and all things consumable — a theme that would never again be repeated for future World’s Fairs. Organizers turned to private financing and the sale of bonds to pay the huge costs of putting on the fair. The 1939/1940 World’s Fair ended in financial failure, and organizers saw the 1964/1965 Fair as a means to finish what the earlier fair had begun. To ensure profits to complete the park, fair organizers knew they would have to maximize gate receipts by having a 2-year fair.

Many of the pavilions were built in a Mid-Century modern style that was heavily influenced by Googie architecture defined as: “a form of modern architecture originating in Southern California in the late 1940s as a subdivision of futurist architecture influenced by car culture, jets, the Space Age, and the Atomic Age.” Some pavilions were explicitly shaped like the product they were promoting, such as the U.S. Royal tire-shaped Ferris wheel and the innovative fiberglass Seven-Up Tower; or as the corporate logo, such as the Johnson Wax pavilion. Other pavilions were more abstract representations, like the football shaped IBM pavilion, or the General Electric dome shaped “Carousel of Progress” that would influence sports stadium design for the next two decades.

Although opened after his death, tributes to President John F. Kennedy could be found all over the fairgrounds. Kennedy had broken ground for the pavilion in December 1962 but was killed in November 1963. More than two million people took a ride on the 80-foot-tall tire shaped Ferris Wheel, including Jackie Kennedy and her children. The fair’s edginess was not only confined entirely to shape, but also to composition. A new-found freedom of form was actuated by the use of modern building materials, such as reinforced concrete, fiberglass, plastic, tempered glass, and stainless steel. The contrast between these new construction techniques with the smaller international, U.S. state, and organizational pavilions built in more traditional styles, such as a Swiss chalet or a Chinese temple, was fantastic.

New York City in 1964-65 was at a zenith of economic power and world prestige. With the larger nations boycotting the fair, smaller nations saw it as a chance to shine. Spain, Vatican City, Japan, Mexico, Sweden, Austria, Denmark, Thailand, the Philippines, Greece, Pakistan, and Ireland made impressive showings at the Fair. Indonesia sponsored a pavilion for 1964 but bailed for 1965 as relations deteriorated rapidly with the U.S. during 1964. Indonesia withdrew from the United Nations in January 1965 and it remained closed and barricaded for the 1965 season.

The U.S. Pavilion was titled “Challenge to Greatness” and focused on President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society proposals. The main show in the multi-million dollar pavilion was a 15-minute ride through a filmed presentation of American history. Visitors seated in moving grandstands rode past movie screens that slid in, out and over the path of the traveling audience.

A two-acre United States Space Park was sponsored by NASA and the Department of Defense. Exhibits included a full-scale model of a Saturn V rocket that would send astronauts to the moon within the decade, a Titan II booster with a Gemini capsule and an Atlas with a Mercury capsule. On display at ground level were Aurora 7, the Mercury capsule flown by Scott Carpenter on the fourth U.S. manned orbital flight, a Gemini spacecraft, an Apollo command/service module, and a Lunar Excursion Module of the type used by Apollo 11 to land on the moon. All of these images might seem mundane to us now, but it should be remembered that these were displayed well before they became familiar imagery to space fans.

One of the fair’s most popular exhibits was the Vatican Pavilion, where Michelangelo’s Pietà was displayed and brought in from St. Peter’s Basilica with the permission of Pope John XXIII. A recreated medieval Belgian village proved very popular mostly because fairgoers were treated to the “Bel-Gem Brussels Waffle” — a combination of waffle, strawberries and whipped cream — for the very first time.

The Ford Motor Company introduced the Ford Mustang automobile to the public at its pavilion on April 17, 1964. Toshiba’s booth featured a “Pickup Storage Tube” camera that allowed visitors to pose for film-less photos that were displayed on a TV screen as a forerunner of today’s digital cameras. The Bell System demonstrated a crude, but effective, prototype of a video telephone as an early forerunner of today’s Skype. Oh yeah, fairgoers watched as guys zoomed around the fairgrounds spectacularly on jetpacks, but we’re all still waiting for that to happen. I don’t mention computers as “firsts” at the fair because they were everywhere at the 1964-65 Fair. No doubt those early versions were the first time computers were seen, and used, as routine efficiency enhanced tools.

During the 1939 World’s Fair, RCA introduced TV to a mass audience for the first time. In 1964, they topped that experience by debuting color television at the Fair. Architect Minoru Yamasaki revealed his concept for the World Trade Center in 1964 with a scale model of the Twin Towers at the fair’s Port Authority Building. Other popular exhibits included the Sinclair Oil Corporation sponsored Dinoland, featuring life-size replicas of nine different dinosaurs, including the corporation’s signature Brontosaurus mascot. And although technically, the New York Mets’ brand-new Shea stadium wasn’t part of the expo, visitors could check out the 55,000-seat venue as they took a special train from the fairgrounds. The Amazin’s played the Pittsburgh Pirates during the inaugural game on April 17, 1964 (5 days before the Fair opened), but lost by one run.

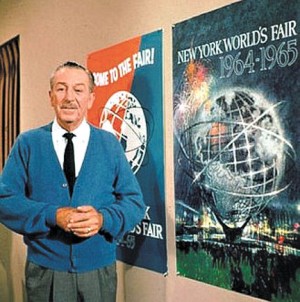

Perhaps more than anything, the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair is remembered as the venue Walt Disney used to hone his skills. It was at this Fair where Uncle Walt would perfect themes and machines used in Disneyland and Disney World in rides that are oh so familiar to us all to this very day.

Next Week: Part II — My World’s Fair Daydream…50 Years On.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest book is “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.