The inventor of basketball, Dr. James Naismith, was born in 1861 at the outbreak of the American Civil War. He lived long enough to see the game he created become an official event at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, as well as the birth of both the National Invitation Tournament in 1938 and the NCAA Men’s Division I Basketball Championship in 1939. He also managed to visit Indiana for a pair of IHSAA tournament finals in Indianapolis. While here, he acknowledged that although basketball may have been born in Massachusetts, it grew up in Indiana.

Naismith’s game was simple. It required a soccer ball and a pair of peach baskets. The first game was played in December 1891 with nine players on each squad. In a handwritten report, Naismith described that inaugural match: “When Mr. Stubbins brot [sic] up the peach baskets to the gym I secured them on the inside of the railing of the gallery. This was about 10 feet from the floor, one at each end of the gymnasium. I then put the 13 rules on the bulletin board just behind the instructor’s platform, secured a soccer ball and awaited the arrival of the class… The class did not show much enthusiasm but followed my lead… I then explained what they had to do to make goals, tossed the ball up between the two center men & tried to keep them somewhat near the rules. Most of the fouls were called for running with the ball, though tackling the man with the ball was not uncommon.”

In contrast to modern basketball, the original rules did not include dribbling or rebounding. Since the ball could only be moved up the court via a pass, early players tossed the ball over their heads to teammates as they ran down court. The earliest games featured peach baskets attached to a pole with no backboard; hence, no rebounds. After each “goal,” a jump ball was taken in the middle of the court. The original Naismith 13 rules remain, more or less, familiar.

And speaking of those original rules, whatever became of them? Not long after Naismith’s class played the first game of basketball, the original rules went missing from the gymnasium bulletin board. According to Naismith’s book, Basketball: Its Origin and Development, before class one day, a tackle on the football team from North Carolina named Frank Mahan approached Dr. Naismith. “You remember the rules that were put on the bulletin board?” Mahan said. “Yes I do, they disappeared.” Naismith said. “I know it, I took them,” Mahan admitted. “I knew that this game would be a success, and I took them as a souvenir.” Mahan returned them to Naismith that afternoon. From that time on, Dr. Naismith cherished those original rules, but he couldn’t imagine their potential value. In June 1931, after urging from his son Jimmy, Naismith officially signed the rules, thereby transforming what before were two pieces of paper into the Holy Grail for hardwood historians.

Naismith never sought fame or fortune for his invention. In the tradition of American heroes like Benjamin Franklin (electricity), Arsenal Tech Grad Howard Aiken (the computer) and Dr. Jonas Salk (polio vaccine), Naismith refused to profit from his creation. He resisted an early movement by his students to name the new game “Naismith Ball,” insisting that the game be known as “Basket Ball” instead. Always humble and never self-promotional, Naismith avoided drawing attention to himself as the game’s inventor. Mainly a coach and teacher, Naismith played only two official basketball games in his lifetime: a public match in Springfield in 1892, and a game at the University of Kansas, where he served as assistant gymnasium director, in 1898.

Naismith had offers to do commercials and advertisement campaigns, but except for lending his name as endorsement for a Rawlings basketball, he declined. “I am sure that no man can derive more pleasure from money or power than I do from seeing a pair of basketball goals in some out of the way place,” he once wrote. After setting his new sport in motion, Naismith went on to pursue the career he had envisioned for himself, combining fitness and spirituality for a healthy body and a healthy mind. He continued preaching, stayed involved with Kansas University and watched from afar as his original 13 rules evolved. He delighted in receiving letters from people playing basketball all over the world. He was not only the inventor of the game, he was it’s most ardent fan. And he remarked on visits to the IHSAA tournament in 1925 and 1936 that no one understood his game better than Indiana.

As the years passed, the game was no longer Naismith’s. Instead, as he wrote, it “belonged to the public.” During his lifetime Naismith received degrees in philosophy, religion, physical education, and medicine, but it was not until after his death that this humble Presbyterian minister received his own measure of immortality for his contribution to sports history. Naismith suffered a major brain hemorrhage on November 19, 1939 and died nine days later in his home located in Lawrence, Kansas. He was 78 years old. In 1959, he was posthumously enshrined as the first member of the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Massachusetts.

After his death, the family placed Naismith’s original 13 rules in a series of safe deposit boxes. In the meantime, basketball grew into the second most popular sport in America (behind football, according to Google) and salaries eclipsed the GNP of some small countries. Over time, those two typed sheets started gaining value. The family was offered $1 million for the rules in the 1960s, $2 million in the 1970s and $5 million in the 1990s. Still, the rules stayed with the family and in the box.

The value, along with the cost of insuring and protecting the original rules now made displaying the documents with Dr. Naismith’s hand-written notations, date and signature, prohibitive. The relics were almost permanently consigned to the safe deposit box. In 2010, the North Carolina-based Naismith International Basketball Foundation, dedicated to promoting youth sports, began to struggle financially. Dr. Naismith’s grandson Ian decided it was time to do something good with his grandfather’s relics. Dr. James Naismith was orphaned at age 9, so his grandson insisted that children benefit from his grandfather’s work.

I met Ian Naismith in 2010 when he was in town during the Final Four in Indianapolis. The outspoken and friendly Naismith, who lived in Burlington, Illinois near Chicago at the time, told me about the plan to sell the rules. Ian said recent appraisals placed the document’s value at $5-10 million, so he expected to get over a million dollars for them. He told me he wanted to invest that money in promoting good sportsmanship in youth sports. He explained that he felt basketball was losing sight of sportsmanship, amateurism and other aspects he believed his grandfather held dear. Ian’s outspoken views and beliefs often caused him to publicly clash with the NCAA, NBA, Hall of Fame and other agencies. But no one ever questioned his love for the game.

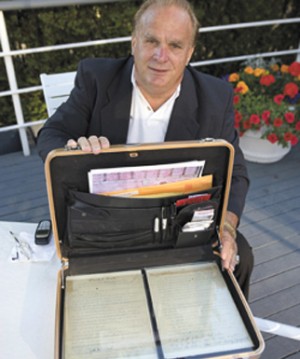

Mr. Naismith had been touring with the basketball memorabilia since 1999. While touring the country, he carried the written rules in a gold suitcase handcuffed to his wrist. Ian brought his fantastic display of basketball relics to the NCAA Hall of Champions. About 30,000 fans viewed the original rules, which one local writer called the “Magna Carta of basketball,” and Mr. Naismith proudly said that not one of them paid a cent. “The exhibit has always been free,” Mr. Naismith said. “No one in my family has ever made money from basketball, though we could have. Other people get rich off the game. My grandfather would not like that, and I do not like it. I’m not rich, I do this because I believe in my family, I believe in the game and I believe in the kids.”

Naismith was one of the most down-to-earth people I’ve ever met. He revealed that he was battling the effects of a 2007 stroke that forced him to relearn how to walk and talk. He was almost constantly seated or leaning against something during our conversation, remarking that his legs often ached as a result of the stroke. During our talk, he removed his wallet and showed me a picture of his lovely wife, Renee, whom he lost to cancer a few years before. He was also nursing a nagging cough from a recent bout with pneumonia.

Shortly after the exhibit closed, Ian sent James Naismith’s original 1891 set of 13 rules to Sotheby’s auction house in New York City. On December 10, 2010, the rules were sold for $3.7 million ($4,338,500 including buyer’s premium). It was the largest single sale ever transacted for a piece of American sports memorabilia. The buyer was David Booth, a billionaire who is chairman and co-CEO of a Texas mutual fund company, who purchased them for display at his alma mater, the University of Kansas, where Naismith was a coach and educator for decades.

One of my funniest memories from my visit with Ian Naismith came when I asked how old he was and he laughed, blushed and literally pled the 5th. He wouldn’t tell and to be honest I couldn’t tell. He looked good, he sounded good and when he did move around (which was often during the exhibit) he moved well. If you read my column regularly, you know I follow auctions so I was happy for Ian and his foundation when I heard the news of the sale. I was equally shocked when I learned a little over a year later that Ian Naismith was dead.

On March 21, 2012, Ian Naismith, grandson of the inventor of basketball James Naismith, was traveling on the Tuesday train from western Massachusetts to New York City. The train pulled into New York’s Penn Station, and people on the train thought he was asleep, turns out, Naismith died of a heart attack. The Naismith The International Basketball Foundation listed Ian Naismith’s age at time of death at 72 but Ian’s hometown newspaper pegged his age at 73. By my count, that would’ve made Ian an infant in his “terrible twos” when his famous inventor grandfather died in 1939. Basketball requires two teams, two courts, two baskets and two halfs. I think Grandpa Naismith would smile at that.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest book is “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.