When I was a kid, like most Hoosiers, I visited Chicago often. I was as big a history nerd back then as I am today. I made sure to visit the obvious places: the St. Valentines Day Massacre site, the alley next to the Biograph Theatre where Johnny Dillinger breathed his last, Wrigley Field, Soldier Field, McCormick Place (site of the Century of Progress World’s Fair of 1933-34). But there was another Chicago location that I insisted on visiting as a kid, regardless of the vocal protestations of my parents. It’s a small plot of land inside Woodlawn Cemetery in Forest Park, Illinois known as “Showmen’s Rest.” And the event that brought me there happened 95 years ago this week.

In the early pre-dawn hours of Saturday June 22, 1918, a Michigan Central Railroad troop train struck the rear of the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus train near Ivanhoe, Indiana. Located in the center of the geographic triangle between Hammond, East Chicago and Gary, Ivanhoe never knew what hit ‘em.

On that fateful morning, the 26-car circus train, consisting of an engine, four sleepers, five stock cars, fifteen flat cars and a caboose, was heading from Illinois into Hammond, Indiana, with 400 performers and roustabouts asleep in the rear cars. The train had stopped on the Michigan Central tracks near Ivanhoe to fix an overheated axle box. The flagman went back on the main track and set fuses as a warning of danger. The Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus train had been moved onto a siding while it awaited clearance to proceed onto the line to Hammond where the circus was due to perform. The rear of the train, however, had not cleared the mainline tracks.

At 3:56 a.m., engineer Alonzo K. Sargent fell asleep. He never saw the danger on the tracks ahead as his empty twenty-one car troop train plowed into the rear of the stationary train at 60 mph. Despite the warning signals, lanterns and flares blanketing the track leading up to the stalled train, 86 people died and 127 were injured. Many of those bodies were recovered from the burnt-out wreckage of the wooden, gas-lit passenger cars. The runaway train finally came to a grinding halt atop the fourth car from the rear in a deafening cacophony of metal and splintered wood. Most of the 86 dead perished within the first 30 seconds of the wreck. Then, just as the nightmare seemed to be over, the train caught on fire.

Fire, fed by the gas-lighting system of the circus train, quickly engulfed the train. As the first responders reached the scene, the entire wreckage was a blazing inferno. Clowns, bareback riders, trapeze performers and acrobats, many of them veterans of the circus world, perished instantly in the crash while others were suffocated or burned to death. The Gary fire department was hamstrung further in their rescue attempts due to a lack of water supply. Survivors struggled about the wreck screaming for relatives or friends and many had to be physically restrained from rushing back into the blazing wreckage.

Hours after the crash, bodies were still being recovered from the pile of debris. There were numerous pitiful scenes at the wreck and later in the hospitals. Joe Coyle, a clown, convulsed on a stretcher and wept bitterly beside the bodies of his wife and two babies who had been crushed to death just inches away from him inside one of the death cars.

Adding to the chaos, rumors sped through the area that several lions, tigers, elephants and bears had escaped from the train into the woods south of the wreck. Circus authorities explained that there were no wild animals on the train. Another report claimed that one demented circus woman had run from the train, evaded the doctors and disappeared into the woods. It’s easy to imagine the wild rumors that must have swept that small town after a tragedy of this magnitude.

Engineer Alonzo K. Sargent was arrested that same night and charged with multiple counts of manslaughter. The headlines of the local papers explained the tragedy in detailed, sometimes colorful, terms: SIXTY HEROES OF THE SAWDUST RING PERISH IN FLAMING WRECK AS TRAIN CUTS THRU CARS… SOMEBODY’S BLUNDER COSTS IN KILLED AND INJURED 189 CASUALTIES OF WALLACE-HAGENBACK CIRCUS…PERFORMERS WEAKENED BY CRASH TO DIE IN FLAMES… FAMILIES LONG KNOWN TO PUBLIC AS FAVORITES ARE DECIMATED OR SWEPT TO ETERNITY. Despite being found responsible by federal transportation officials (the cause was sleeping on the job, they said) Engineer Sargent was acquitted.

Thirty-eight bodies were taken to Gary undertakers, twenty-two were taken to Hammond. Later, more bodies were pulled from the wreckage and still more died in the hospital afterwards. Four days after the crash, survivors gathered at Woodlawn Cemetery, where the Showmen’s League of America had just recently selected a burial plot for members, never imagining that it would be used so soon. The Showmen’s League of America was formed in 1913 with Buffalo Bill Cody as its first president.

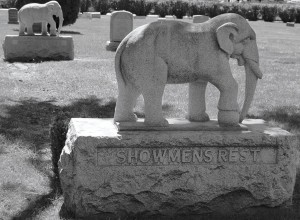

Walk into Woodlawn cemetery, located at the intersection of Cermak Road and Des Plaines Avenue in Forest Park, Illinois, and the first thing you’ll notice are the five elephant statues encircling the plot containing 750 grave sites known as Showmen’s Rest. The rumor, perpetuated by generations of Illinois schoolchildren and spread through classrooms all over the Midwest, is that there were 5 elephants killed in the train wreck. The elephants tried in vain to use their trunks to extinguish the burning circus cars, only to die for their efforts. The pachyderm heroes were too heavy to be moved and were buried near the spot where they fell. Contrarily, the statues actually outline the site of the mass grave containing the mortal remains of the unfortunate Hagenbeck-Wallace circus employees killed on the circus train in the early days of World War I.

Forest Park, the site of Showmen’s Rest, is a town of cemeteries, marking the historical fringe of metropolitan Chicago. Public transportation terminated here, so it seemed like the perfect place for Chicago’s deceased populace. Today, strip malls and fast food joints have crept in, but endless fields of monuments still silently greet the Windy City visitor.

Services for the circus train tragedy were held five days after the train wreck. The identity of many victims of the wreck was unknown; some were roustabouts and temporary workers hired just hours or days before. Only a dozen or so of the headstones have names, most of the markers note “unidentified male” (or female). One is marked “Smiley,” another “Baldy,” and “4 Horse Driver.” The Flying Wards, a trapeze act, lost a member; every one of the McDhu Sisters, who rode elephants and did aerial stunts, died. Two strongmen died. Showmen’s Rest continues to fill up today, with deceased showmen performing at that biggest of Big Tops.

Following the wreck, the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus had to cancel only two performances: the one in Hammond, Indiana and its next stop Monroe, Wisconsin. This was due in part by the assistance by many of its so-called competitors, including Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus lending needed equipment and performers so that the show could go on. The Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus, formed in 1907 and headquartered in Peru, Ind. (now the site of the International Circus Hall of Fame), had become one of the most popular circuses in the country. Famed lion tamer Clyde Beatty was a member. So was a young Red Skelton, tagging alongside his father, a Hagenbeck-Wallace clown.

The city of Hammond also joined in to help the surviving circus performers and workers. Many of the city’s residents and shopkeepers gave food and clothing as well. The five elephant statues each have a foot raised with a ball underneath, and the trunks lowered. (Raised trunks are a symbol of joy and excitement; lowered trunks symbolize mourning.) The base of the large central elephant is inscribed with “Showmen’s League of America.” On the others are the words “Showmen’s Rest.” Some nearby residents say the trumpeting sounds of ghostly elephants can often be heard at night, even though there were no elephants buried there and the statues weren’t added until years after the train wreck. And for those looking for an explanation for the sounds, Brookfield Zoo is only a few miles away.

The history of the train wreck is a mix of the good, sad and curious. The accident led to regulations mandating sleep for train crews. Oddly, nine years later, a passenger train moving through Aurora, Indiana (near Cincinnati, Ohio) hit a herd of elephants being loaded onto another Hagenbeck-Wallace train; there was one fatality, a handler riding one of the elephants was thrown to the ground and crushed to death when the animal tumbled. But my memory? I recall that there was nothing at Showmen’s Rest, or for that matter at the site of the tragedy, that mentions the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus disaster, the loss of life or anything about June 22, 1918. You had to know it’s there to know it’s there. Now you too know it’s there.

Al Hunter is the author of “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Indiana National Road” and “Haunted Irvington” book series. Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.