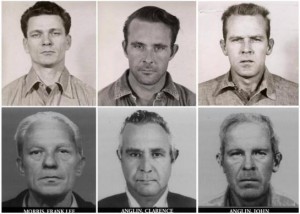

Last week, we examined one of two anniversaries that, although disparate in nature and a quarter century apart, have woven themselves into the tapestry of American conspiracy — the mysterious disappearance of pioneer female aviator Amelia Earhart on July 2, 1937 and the escape and disappearance of Alcatraz inmates John Anglin, Clarence Anglin and Frank Morris, on June 11, 1962. Earhart’s vanishing was an tragedy that resulted in the largest “manhunt” in American history. Conversely, the Alcatraz escape was a well-planned plot to flee the island prison — and the intense search by law enforcement eclipsed the Earhart rescue effort made 25 years before.

By now, the details of the escape are well known but worth revisiting. The plot was in the planning stages as early as the summer of 1961. Morris and the Anglin brothers, along with another inmate named Allen West, met while serving time together in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. The quartet was sent to the Rock for (surprise!) repeated escape attempts. Although they arrived at different times (from 1957 to 1961), once they arrived they began to plot their elaborate escape. These guys were professional escape artists and it didn’t take them long to figure out that the aging island prison was literally crumbling beneath their feet after decades of exposure to the harsh sea air.

Legend has it that the inmates burrowed their way out using spoons taken from the prison dining hall, but most experts discount that claim as dubious at best. It is more likely that the shrewd thinking cons converted common prison electric devices (such as electric fans) into makeshift drills to punch through the six-and-one-half inch cell walls in the rear of their cells. By late May 1962, after a year’s worth of work, they had finished making a shoebox sized hole that allowed them access to the utility corridor and ultimately, the prison roof.

On the night of June 11, 1962, they squeezed out of their cells, climbed the ventilation shaft (using the water pipes as makeshift ladder rungs) to the roof and repelled down to flee the island on a makeshift raft. Allen West did not make it out of his cell and was left behind. The trio placed dummy heads, whom John and Clarence gave the pet names of “Oink” and “Oscar,” in their beds to fool prison officers during night-time head counts. The realistic looking heads were made out of a mixture of soap, cement dust, toilet paper and real hair (collected from the prison barber shop floor) and finished off with flesh colored paint from prison-issued art kits.

The trio made it to the rocky shoreline on the northeastern coast of the island, pumped up their rubber raft (made of the prison’s standard issue raincoats and contact cement), jumped in and paddled away into the night…and history.

It is unknown what occurred after the inmates launched the raft. Although I will tell you that my friend Jim Albright, the last guard off the island of Alcatraz and one of the guards on duty the night of the escape, told me that he personally believes that the Anglin brothers killed Morris shortly after their departure to hasten their escape. The day after the escape, remnants of the makeshift raft, paddles, and a bag containing the Anglins’ personal effects were found washed up on the shore of Angel Island, two miles from Alcatraz.

Since that time, just as with the disappearance of Amelia Earhart, speculation abounds as to the fate of the subjects involved. Did they make it? Could they make it? Are they marooned on some lonely island or living quietly in plain sight?

At least in the Anglin’s case, there are two Florida women who have no doubt that the convicts made it safely off the island. For Marie Widner and Mearl Taylor, the younger sisters of John and Clarence Anglin, the “Escape from Alcatraz” is all about family. On a recent visit to the stomping grounds of her big brothers on Alcatraz, the 76-year-old Widner said, “I’ve always believed they made it, and I haven’t changed my mind yet.”

Widner’s sons arranged for their mother and aunt to visit Alcatraz because they wanted, in Kenneth Widner’s words, “to clear up some misnomers about the boys.” Among those that rankle Mearl Taylor the most is the idea that her brothers were simple-minded hard-core criminals who deferred to Morris’ escape plan without contribution. Like Morris, the Anglin brothers were serving heavy sentences for non-violent crimes, but it was the pair’s history of previous escape attempts that got them sent to Alcatraz. For the record, Morris, who has no known relatives, reportedly had an IQ of 133, which is in the top 3 percent.

“Just because they did this mischievous stuff growing up, they were not bad boys. They never caused no problems with the family. They just got out and did this mischievous stuff until it got to the bank robbery and that’s when they really got into trouble. I’m proud of them.” Taylor said. “If they thought they were dead, why keep looking for them?” her son, Dave Anglin, said, adding that his uncles were good swimmers who “used to break the ice in Lake Michigan.”

Proud of them or not, out of the 36 Alcatraz inmates who attempted escape before it closed in March of 1963, Morris and the Anglin brothers are the only ones who remain unaccounted for. The U.S. Marshal’s Service, who took over the manhunt from the F.B.I. in 1978 and maintains active arrest warrants on the trio to this day, does not take that fact lightly.

Logic notwithstanding, U.S. Marshal Michael Dyke, who inherited the unsolved case in 2003, does not disagree with the sisters’ account. Realistically, Dyke has no idea whether the trio is still alive, but he’s seen enough evidence to make him wonder. At last report, Dyke remains busy tracking down over 250 recent tips and reported sightings of the escaped convicts. He continues to receive tips almost every month, some credible and some just plain wacky.

The clues he considers the most tantalizing are credible reports that for many years the Anglins’ mother received flowers delivered mysteriously without a card, reportedly from the Anglin boys. When she died in 1973, the family claimed that the brothers attended her funeral disguised in women’s clothes despite a heavy FBI presence. “We have to operate under the assumption they made it,” Dyke said. If the Anglins or Morris were to surface today, Dyke said he would arrest them, but “I’d have to compliment them because it was very meticulous what they did, how they escaped. Then I’d tell them its time to go back to jail now.” Federal prosecutors would then have to decide whether to charge them. The warrants on the trio of escapees will expire when each man passes his 100th birthday.

In the end, authorities pointed out that the chances of all three surviving the trip across the bay were slim. At the time, there were no reports of robberies or car thefts in the Bay area that could have been attributed to them, and the men were habitual criminals yet were never arrested again. The FBI officially closed the case on December 31, 1979, concluding that “no credible evidence emerged to suggest the men were still alive.”

That same year, the film Escape from Alcatraz starring Clint Eastwood hit the movie theatres and the survival theories heated up. Unsolved Mysteries aired an episode claiming that the men might well have survived the escape, offering as proof a report that a day after the escape a man claiming to be John Anglin called a San Francisco lawyer seeking to arrange a meeting with the U.S. Marshals’ Office. When the lawyer refused, the caller hung up.

A statistical perspective lends authority to the survival idea that at least one or two of the escapees survived the treacherous bay crossing, because the bodies of two out of every three people who go missing in San Francisco Bay are recovered. Whether the three men perished in chilly San Francisco Bay, as prison officials and federal agents insisted at the time, will always remain a subject of hot speculation because their bodies were never found.

Just as the continued discovery of items purportedly belonging to Amelia Earhart on Gardner Island will fan the flames for an answer as to her whereabouts, the unrecovered bodies and open arrest warrants will forever add fuel to the fire of the Alcatraz escapees “survival theory.”

Amelia Earhart is an American icon, a role model for women worldwide and a figure destined to be forever shrouded in mystery. At the top of her game, surrounded by state-of-the-art aviation equipment and tracked by countless fans looking skyward she nonetheless disappeared from the face of the earth 75 years ago this month.

The Anglin brothers and Frank Morris were the other side of that coin. They were a trio of down-on-their-luck bank robbers who never hurt anybody but who still managed to land in the toughest prison in America apparently destined to be heard from no more. The fact is, these two unlikely events are forever joined together by their dual common denominator; fame and the sea. Whether or not they lived one moment past hitting the water, they are destined to live forever as unsolved American mysteries.

By the way, if they survived, Frank Morris would be 85, John Anglin would be 82, and Clarence Anglin 81. Amelia Earhart’s birthday is July 24th, this coming Tuesday.

Al Hunter is the co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.