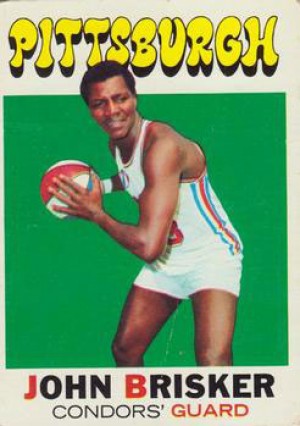

For three seasons (1969-71), John Brisker ruled the ABA. He averaged 26.1 pts per game, which is crazy good, but more importantly, he led the league in fights and his intimidation factor was off the charts. In an outlaw league filled with castoffs and misfits, John Brisker topped them all. Executives placated him, coaches hated him, opposing players feared him, and even his own teammates refused to guard him during practice — all of which was perfectly fine with John Brisker.

Brisker’s temper showed his dark side, but he was also highly intelligent. He was proud of his African heritage and studied African culture by reading and researching the subject whenever he could. He began to wear a dashiki (a loose, brightly colored African shirt or tunic) as a way of exhibiting his African pride. Although readily accepted today, at the time, it made Brisker a target of inquiry. Some within the establishment pegged him as a black militant.

During his three seasons in Pittsburgh under two different team names (Pipers and Condors) Brisker also found trouble off the court. In the fall of 1971, he attended a Pirates World Series home game with a girlfriend. After hailing a cab at the end of the game, Brisker got in an argument with a man who claimed that he had reserved the cab ahead of time. Brisker refused to get out of the cab, resulting in a fist fight with the man. Three nearby policemen spotted the brawl and as they investigated, Brisker began fighting the cops, too. Two of the three officers were hospitalized and Brisker was arrested for assault and battery, disorderly conduct and resisting arrest. The handwriting was on the wall for John Brisker.

Brisker decided to cash in his ABA success by signing a lucrative multi-year contract with the NBA’s Seattle SuperSonics. Los Angeles businessmen Sam Schulman, the Sonics’ owner, was threatening to move his team to the ABA and worse, to move his soon-to-be ABA team to L.A. to compete directly with the Lakers. The Sonics had just signed Brisker’s Detroit neighbor and ABA All-Star Spencer Haywood the season before. Brisker had come in second to Haywood for ABA Rookie-of-The-Year honors in 1969-70. So it seemed like a good fit for everyone involved, including the fans.

It was a good financial move, but it came at a steep price for Brisker. The NBA was not as tolerant of Brisker’s bruising brawls as the ABA had been and his new teammates, perhaps dubious of the ABA hype, were not as accepting of him. NBA players didn’t scare so easily, and they knew he wasn’t going to risk a suspension, with its fine and loss of pay. Still, old habits die hard and during one Sonic scrimmage, Brisker got in a shoving match with a teammate, knocking out the player’s front teeth. That move prompted one Seattle Post-Intelligencer columnist to induct Brisker into the Seattle Boxing Hall of Fame. So, faced with this new reality, Brisker did his best to fit in. Despite his negative reputation, he became a positive force in the community, always the first to volunteer to attend charity functions during the offseason. Brisker also liked to run basketball clinics for underprivileged youth from Seattle’s slums, always at his own expense.

“I want to play here, in this city, for these fans,” Brisker said. Any plans for conformity and NBA normalcy by Brisker were derailed during the 1973-74 season when the SuperSonics hired former Boston Celtic great Bill Russell as their new head coach. Brisker quickly found himself at odds with Russell, an old school NBAer who was a believer in strict discipline, practice, and a strong defense. Russell’s philosophy did not mesh with the free-spirited offensive-minded forward.

Although still a powerful presence both on and off the court, the Sonics demoted Brisker to the CBA’s Eastern Basketball League after only 35 games, even though John was averaging a healthy 12.5 points per game. Russell said Brisker “lacked discipline” and he “sent him down to learn to play some defense.” Brisker, obviously thinking a good offense beats a good defense every time, scored 56 in his first CBA outing. The next season saw more of the same with Brisker playing in only 21 games and averaging a career low 7.7 ppg. By the time Brisker collected the third paycheck of his third season he was out of Seattle’s starting line-up.

Sonics owner Sam Schulman claimed that Brisker was sparking “dissension” in the club and released him prior to the 1975-76 season. No other teams showed interest in signing him, leading many to believe Brisker had been blackballed by professional basketball. So Brisker gave up on his playing career. The world lost contact with him by the late 70s. Brisker played six seasons in the ABA and NBA, averaging 20.7 points per game for his career (26.1 points per game in the ABA, and 11.9 points per game in the NBA). Brisker’s enigmatic, mercurial life, like his career, was about to take its strangest turn.

In 1978, Brisker boarded a flight to Africa and was never seen again. He told family and friends that he had plans to get into the import-export business in Idi Amin’s Uganda. Other than a occasional long distance phone call or photo from abroad, Brisker’s family lost touch with him forever. His brother “Rapid Ralph” Brisker, himself a former college basketball star, said John had been invited to Uganda as a guest of President Amin, a wild basketball enthusiast. The most often repeated contemporary rumor claims Brisker went to Uganda to fight as a mercenary soldier in the jungles of Africa.

When it came to Brisker’s whereabouts after 1978, John’s family offered similar variations of the same narrative:. “John was into a black separatist thing. Black power. Black business for black people. Black communities with black leaders.” Mark Brisker, a nephew who bounced around the Euro leagues for a few years, told him Uncle John had sent the family a picture from Africa of him on horseback. He signed it, “Have money will travel, John.” Brisker’s last contact came in a phone call came from Kampala, the capital and largest city of Uganda. Then literally, dead silence.

For years more wild rumors began to circulate. Brisker was on the run from the Feds. Brisker was on the run from the mob. Brisker fell in with some shady Liberian grifters. Brisker is alive and well living under an assumed identity in Africa. Brisker made it back to the States and is still alive. Another rumor claimed that Brisker was hired to coach the Ugandan National basketball team, ended up arguing with Amin and ended up as just another of the bloodthirsty tyrant’s many corpses. The wildest rumor claims that Brisker died in the Jonestown massacre orchestrated by cult leader (and former Hoosier) Jim Jones. Perhaps the most plausible explanation is that Brisker, who was living in the Royal Palace at Amin’s invitation, was executed by a firing squad of revolutionaries when the brutal dictator was removed from power in 1979. The State Department and FBI checked out that angle and came up empty-handed.

No official documentation tying him to Amin has ever been located. Officially Brisker was considered missing. That remained his status until 1985, when Seattle’s King County medical examiner finally declared him dead at the age of 38. That declaration paved the way for Brisker’s family to lay claim to his estate, modest as it was. His body was never found and his remains are believed to be buried somewhere in the steamy, impenetrable jungles that surround the capitol of Uganda. All anyone knows for sure is that this ungentle giant’s light shone all too briefly before flaming out completely in a post-merger age. An age where Brisker should have been an established vet on his way to the Hall of Fame.

Still, there are some who believe that Brisker remains alive and simply does not want to be found, choosing instead to live his life in anonymity wherever that may be. John Brisker exuded the requisite toughness necessary to survive the mean streets of Detroit of the 1960s. “In Detroit, if you’re tough enough,” Brisker once told a reporter, “they name playgrounds for you.” Brisker used to play ball at a playground located between Hamtramck High School and Highland Park. Sure enough, the playground would be named after John Brisker. In a sense, it’s the most fitting epitaph to this enigmatic figure. John Brisker’s disappearance had a spiritual, antithetic quality to it; the adventurer-narrative of a lost soul journeying to a lost land for a lost cause. And then the soul vanishes. The mystery surrounding his fate only adds to the legend of John Brisker and the ABA.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest book is “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.