On March 1 & 2, 1978, 24-year-old Polish refugee Roman Wardas, and his cohort, Bulgarian Gantscho Ganev, aged 38, entered a small country graveyard in Corsier-sur-Vevey, Switzerland to dig up Hollywood movie legend Charlie Chaplin, who had died on Christmas Day of 1977. The weather was right out of central casting. At 11 p.m., the atmosphere was thick with fog, peppered by freezing haar, and plagued by a troublesome mist. A light rain began to fall, then a misty drizzle that morphed into shallow patches of fog. Their search ended at a neat, square, freshly dug plot with remnants of floral memorials. The only sound was the rippling of the faded satin ribbons flapping in the damp breeze.

Although they didn’t realize it, at that moment, the duo were at the zenith of their lives. They stood, staring at the grave, hands clasped atop the shovel handles, chins resting on their oil-stained knuckles. Like pirates from a bygone era, they knew a treasure was beneath their feet. For a few moments, the luckless pair dreamed of their shared idea of setting up their very own car repair shop. A sleek-looking white tile garage fitted with a lift, an automatic tire changer, and an air compressor equipped with a bevy of shiny pneumatic tools ready to serve a large, rich clientele. A shared smile appeared slowly on each man’s face as they turned to each other and nodded. The first step was to start digging. Atmospheric conditions aside, the two were already wet with a cold sweat. Soon the sound of dueling shovels drowned out the usual sounds of the night. As they sunk ever-lower into the earth, the horizon disappeared around them and the panic of not knowing what was going on above them began to set in.

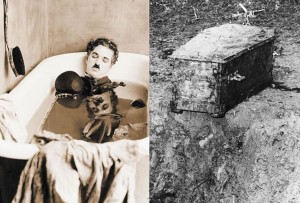

Finally, a shovel hit pay dirt. Shovels gave way to hands and hands gave way to fingers as they quickly excavated the object of their grisly search. It was a 300-pound oak coffin which, although dirty, was intact. The handles still “handled,” and the lid remained closed. These two jobless grease monkeys hefted the coffin out of its eternal resting place and carried it across the cemetery. As they trod, huffing, puffing, and groaning with each labored step, it must have presented an unearthly vision. The men busting through stage curtain sheathes of banks of fog-like characters in a Universal monster movie not knowing what was waiting for them in each clearing from which they emerged. Sliding the coffin into the back of their station wagon, they quickly jumped in and drove off into the darkness. They had done it. They had just stolen the body of the most famous actor in the history of Hollywood. A man so famous that the mere shadow of his waifish tramp-like form was instantly recognizable worldwide: Charlie Chaplin was in the boot of their vehicle.

These two resurrectionists were convinced that their treasure was going to make them very rich, very soon. They arrived at a ransom figure: $600,000 U.S. Dollars (over $2.8 million today). There were a couple of things the grave robbers didn’t count on though. The discovery of the theft of the Little Tramp’s mortal remains sparked outrage and spurred an expansive police investigation. The whole world was watching this tiny isolated Swiss village. But why? The beloved actor who had created the iconic “Tramp” figure so associated with the Golden Age of Hollywood had been out of the limelight since World War II. While Chaplin continued to make films after his classic 1940 movie The Great Dictator, his star never shined as bright as it did during the periods between the two World Wars. Nonetheless, despite the sometimes sordid details of his love life (he was married 4 times between 1920 and 1943 and was rumored to have had many affairs) and the sensational amounts of money he commanded (The Great Dictator grossed an estimated $5 million during the Great Depression — a staggering $110 million in today’s currency), Chaplin remained a beloved figure to generations of fans worldwide.

Looking back, it is easy to understand why. Social commentary was a recurring feature of Chaplin’s films from his earliest days. Charlie always portrayed the underdog in a sympathetic light and his Tramp highlighted the difficulties of the poor. Chaplin incorporated overtly political messages into his films depicting factory workers in dismal conditions (Modern Times), exposing the evils of Fascism (The Great Dictator), his 1947 film Monsieur Verdoux criticized war and capitalism, and his 1957 film A King in New York attacked McCarthyism. Most of Chaplin’s films incorporate elements drawn from his own life, so much so that psychologist Sigmund Freud once declared that Chaplin “always plays only himself as he was in his dismal youth.” His career spanned more than 75 years, from the Victorian era to the Space Age, Chaplin received three Academy Awards and he remains an icon to this day.

Not only did Chaplin change the entertainment industry on film, he changed it in practice as well. At the height of his popularity, wherever he went, Chaplin was plagued by imitators of his Tramp character both on film and on stage. A 1928 lawsuit brought by Chaplin (Chaplin v. Amador, 93 Cal. App. 358), set an legal precedent that lasts to this day. The lawsuit established that a performer’s persona and style, in this case, the Tramp’s “particular kind or type of mustache, old and threadbare hat, clothes and shoes, decrepit derby, ill-fitting vest, tight-fitting coat, trousers and shoes much too large for him, and with this attire, a flexible cane usually carried, swung and bent as he performs his part” is entitled to legal protection from those unfairly mimicking these traits to deceive the public. The case remains an important milestone in the U.S. courts’ ultimate recognition of a “common-law right of publicity” and intelliectual property protection.

By October of 1977, Chaplin’s health had declined to the point that he required near-constant care. On Christmas morning of 1977, Chaplin suffered a stroke in his sleep and died quietly at home at the age of 88. The funeral, two days later on December 27, was a small and private ceremony, per his wishes. Chaplin was laid to rest in the cemetery at Corsier-sur-Vevey, not far from the mansion that had been his home for over a quarter century. But as we have discovered, Chaplin’s “eternal rest” did not last long. After the two ghouls exhumed the body, they found themselves with a new problem. What do we do now? After all, where does one store a corpse in anticipation of a ransom delivery? Thanks to press reports, the duo were aware that Oona Chaplin (Charlie’s fourth wife after Mildred Harris, Lita Grey, and Paulette Goddard) was also the daughter of the playwright Eugene O’Neill. Reportedly, Chaplin had left more than $100 million to his widow ($450 million today). So surely she would not object to paying $600,000 to get her dearly departed husband back, right? But how long would it take to collect that payout?

The body-snatching duo decided they had to do something with Chaplin’s corpse and quickly. So they found a quiet cornfield outside the nearby village of Noville, near where the Rhone River enters Lake Geneva about a mile away from the Chaplin Mansion. Here they dug a large hole and buried the heavy oak coffin with Chaplin in it. Then they waited until the heat died down. Meantime, rumors were flying. Did souvenir hunters steal the body? Was it a carnival sideshow that stole the Little Tramp? Was Chaplin to be buried in England, as he had once requested? The old Nazi speculation about Chaplin’s Jewish ancestry cropped up theorizing that the corpse had been removed for reburial in a Jewish cemetery. All that was forgotten when the kidnappers called Oona Chaplin demanding a $600,000 ransom for the return of the body. The crooks hadn’t counted on what happened next. Suddenly, the Chaplin family, besieged by people wanting the ransom and claiming they had the body, demanded proof that her husband’s remains were actually in their possession.

Body-snatchers Wardas and Ganev had no choice but to schlep back to that field, dig up the coffin, and take a photograph of it as proof that they were the real graverobbers. They excavated the casket and took a photo of it alongside the hole in that cornfield. Then, the two dim-witted graverobbers called the Chaplin Mansion. Well, at least they tried to call. Turns out the number was unlisted so the numbskulls fished around to local reporters, pretending to be reporters themselves, to get the phone number. Needless to say, when the authorities were informed of the scheme, they did not discourage it. At the request of law enforcement, Chaplin’s widow Oona stalled the criminals as she pretended to acquiesce to their ransom demands. At first, Oona refused to pay the ransom, stating “My husband is in heaven and in my heart” arguing that her husband would have seen it as “rather ridiculous.” In response, the criminals made threats to shoot her children. After that, she directed the fiends to the family’s lawyer, who exchanged several telephone calls with the criminals, supposedly while negotiating a lower ransom demand. These stall tactics worked well enough that the police had time to wiretap the phone and trace where the calls were coming from. The savvy criminals used a different telephone box in the Lausanne area for every call, being careful to never use the same call box twice. Undeterred, the investigators enlisted an army of officers to keep tabs on the over 200 telephone boxes in the area. On May 16 (76 days after the grave robbery) the police finally arrested the two men at one of those call boxes.

When taken back to the station, the foolish crooks couldn’t remember the exact spot in the cornfield where they had hidden the coffin. The police swarmed the area with metal detectors and were eventually able to find Chaplin’s remains thanks to the casket’s metal handles. In December of 1978, Roman Wardas and Gantscho Ganev were facing twenty years on charges of desecration of a corpse and extortion. In court, Wardas stated that he had asked Ganev to help him steal the coffin, promising that “the ransom would help them both survive in an environment where employment had not come so readily to them.” Wardas claimed that both men were political refugees and that he had left Poland in search of work, but was virtually destitute in Switzerland. The duo saw the body theft as a “viable financial decision.” The pair had disinterred the coffin and placed it in Ganev’s car, then drove it to the field, where Wardas explained in court that “the body was reburied in a shallow grave“ and that he “did not feel particularly squeamish about interfering with a coffin…I was going to hide it deeper in the same hole originally, but it was raining and the earth got too heavy.” In court, the Chaplin family lawyer, Mr. Jean-Felix Paschoud, asked to speak to “Mr. Rochat,” with whom he had exchanged the ransom calls. Wardas hesitantly stood up from his seat and was wished “good morning” by lawyer Paschoud. Wardas explained that it was he, under the name “Mr. Rochat”, who had made the infamous ransom and threatening phone calls to the family.

Ganev, whom the Swiss court described as “mentally subnormal,” testified coldly that “I was not bothered about lifting the coffin. Death is not so important where I come from.” Ganev testified that he had been imprisoned in Bulgaria after trying to flee to Turkey before finally making his way to Switzerland only to find meager wages working as a mechanic. Ganev claimed that his involvement in the crime was limited only to the excavation, transportation, and reburial of the body, and he had no knowledge of any ransom demand. In testimony, Ganev didn’t think the body snatching was any big deal and acted shocked at the public’s outrage to the crime. When sentencing came down, he was given an 18-month suspended sentence. However, Wardas, whom Ganev had identified as the true mastermind behind the body snatching, was sentenced to 4 1/2 years of hard labor. Both men wrote letters to Oona expressing genuine remorse for their actions. Oona accepted their apologies answering, “Look, I have nothing especially against you and all is forgiven.”

Ganev and Wardas faded from view and were never heard from again. The only unanswered question remaining: did they ever open the casket? As for Chaplin’s body, it was reburied in the original plot. This time under an impregnable concrete tomb (reportedly six feet thick) to prevent any future grave robbing attempts. Chaplin’s final resting place is neat and simple and now his beloved Oona (who died on September 27, 1991, at the age of 66) rests alongside him. Just to the left of the Chaplin plot is the simple grey headstone of another movie star of the Golden Age: James Mason, a close friend of Charlie Chaplin who lived nearby and died in Lausanne in 1984.

Chaplin’s legacy extended well into the computer age. His iconic Tramp character was used as spokes mascot for the original IBM microcomputer from 1981 to 1987 and reappeared briefly in 1991. Not to be outdone, Apple Macintosh used Chaplin’s Tramp for their Macintosh 128K (aka “The MacCharlie”) made by Dayna Communications. Although the ad campaign only lasted a couple of years (1985-87) it remains as a testament to the staying power of a century-old mascot created by one man: Charlie Chaplin.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest books are “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View,” “Irvington Haunts. The Tour Guide,” and “The Mystery of the H.H. Holmes Collection.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.