Visiting Gettysburg has been a constant in my life for nearly 30 years now. If you are a fan of American history, there is no better place for you than Gettysburg. Although it’s been 155 years since the last shots were fired, the landscape of Gettysburg is ever changing and the battle goes on. In the three decades since I first visited the Borough, (in Pennsylvania, they are called Boroughs, not towns) I’ve seen battles over towers, casinos, cycloramas, visitor centers, hotels, railroads, Harley Davidsons and monuments. And the one thing I’ve learned from all of them is that there’s always a story behind the story.

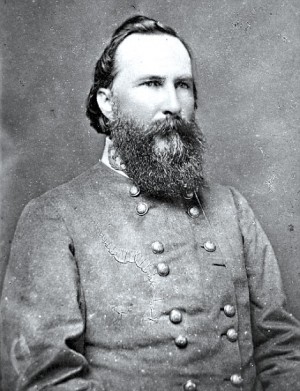

This is a story about a general, a monument, an artist and one of the most interesting women you’ve never heard of. And, like the battlefield itself, this is a story of duty, devotion, romance and controversy. Confederate General James Longstreet is a name familiar to all students of the Civil War. Longstreet, born January 8, 1821, looms large among the luminaries of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy but most likely not in the way you might think. The Lost Cause was a misguided Victorian Era view of the war that downplayed slavery and lionized the Confederate military, resulting in a movement to glorify the Confederate cause as a heroic one against great odds despite its defeat. The ideology continues with the modern day Confederate monument debate I’ve written about in past columns.

Longstreet was the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his “Old War Horse.” He served under Lee as a corps commander in the venerable Army of Northern Virginia, participating in many of the most famous battles of the Civil War. Longstreet’s most controversial service was at the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, where he openly disagreed with General Lee on the tactics used in attacks on Union forces, most notably, the devastation of Pickett’s Charge.

A month after Gettysburg, Longstreet requested and received a transfer to the Western Theatre just in time for the Battle of Chickamauga. Despite the ineptitude of Commanding General Braxton Bragg, Chickamauga became the greatest Confederate victory in the Western Theater and Longstreet deserved and received a good portion of the credit. Longstreet’s enmity towards Bragg ultimately resulted in his return to Lee’s army in Virginia where he soon found himself squared up against his best friend on the Union side, Ulysses S. Grant. Both men served together during the War with Mexico and both served as best man for their weddings. The two men were so close that Longstreet called Grant “Sam” and Grant called Longstreet “Pete.” As further proof of the strong connection between the Generals, Grant married Longstreet’s fourth cousin, Julia Dent, on August 22, 1848.

When Longstreet found out that Grant had been elevated to command of the entire Union Army, he told his fellow officers that “he will fight us every day and every hour until the end of the war.” Longstreet’s attack in the Battle of the Wilderness (May 6, 1864) helped save the Confederate Army from defeat in his first battle back with Lee’s army, but it nearly killed him. The General was wounded during the battle when he was accidentally shot by his own men while reconnoitering between lines. The friendly fire incident took place about 4 miles away from the place where Rebel General Stonewall Jackson suffered the same fate a year earlier.

A bullet passed through Longstreet’s shoulder, severing nerves, and tearing a gash in his throat. General Micah Jenkins, who was riding alongside Longstreet, was also shot and died from his wounds. Longstreet’s wound caused him to miss the rest of the 1864 spring and summer campaign. He rejoined Lee in October 1864 and served admirably during the Siege of Petersburg, the defense of the capital of Richmond, and the surrender at Appomattox. As Lee considered surrender, Longstreet told his commander that he though his friend Grant would treat them fairly, but added, “General, if he does not give us good terms, come back and let us fight it out.” General James Longstreet was a man of contradictions whose story was about to get way more contradictory.

After the close of the Civil War, Longstreet angered his former countrymen by daring to criticize Roert E. Lee, campaigning for Ulysses S Grant and assimilating to life in the Union. In Southern eyes, Longstreet committed blasphemy for critical comments he wrote in his memoirs about General Lee’s wartime performance, by joining Lincoln’s Republican Party and voting for U.S. Grant (twice!) and for accepting work as a diplomat, civil servant, and administrator in the reunified Federal Government of the United States.

However, anti-Longstreet feelings were not just limited to his fellow countrymen. When the “Reconstructed Rebel” applied for a pardon from President Andrew Johnson he was refused, despite a personal endorsement from Union Army General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant. Johnson reportedly told Longstreet in a meeting: “There are three persons of the South who can never receive amnesty: Mr. Davis, General Lee, and yourself. You have given the Union cause too much trouble.” Luckily for Longstreet, the Radical Republicans in the U.S. Congress hated Johnson more than Johnson hated Longstreet and they restored the General his rights of American citizenship in June of 1868.

Leaders of the Lost Cause movement cited Longstreet’s actions at Gettysburg as the main reason for the Confederacy’s loss of the war. When Grant appointed Longstreet as surveyor of customs in New Orleans in 1868, his old friend General D.H. Hill said: “Our scalawag is the local leper of the community.” When Northerners moved South for financial gain, they were called Carpetbaggers, Hill wrote that Longstreet “is a native, which is so much the worse.”

In 1868, the Republican governor of Louisiana appointed Longstreet the adjutant general of the state militia and by 1872 he became a major general in command of all militia and state police forces within the city of New Orleans. Longstreet continued his role as an anathema to his former Confederate colleagues when he led African-American militia against an armed force of 8,400 members of the anti-Reconstruction White League at the Battle of Liberty Place in New Orleans in 1874. Longstreet commanded a force of 3,600 Metropolitan Police, city policemen, and African-American militia troops, armed with two Gatling guns and a battery of artillery.

The White League charged, causing many of Longstreet’s men to flee or surrender, and the General rode to meet the protesters but was pulled from his horse, shot by a spent bullet, and taken prisoner. Federal troops were sent by President Grant to restore order. The outcome of the battle was 38 killed and 79 wounded. Longstreet’s role in this racial battle sealed his fate among his former countrymen. This sad episode ended his political career and he went into semi-retirement on a 65-acre farm near Gainesville, where he raised turkeys and planted orchards and vineyards on terraced ground that his neighbors derisively named “Gettysburg.” A devastating fire on April 9, 1889 (the 24th anniversary of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox) destroyed his house and most of his possessions, including his personal Civil War documents and memorabilia.

The attacks on Longstreet began in earnest on January 19, 1872, the anniversary of Robert E. Lee’s birth and less than two years after Lee died. In a speech at Washington College, former Rebel General Jubal Early exonerated Lee for the defeat at Gettysburg: Early said Longstreet was late. Early claimed Longstreet’s delay on the second day somehow led to the debacle on the third. The following year at the same venue, Lee’s artillery chief William N. Pendleton, charged that Longstreet disobeyed an explicit order to attack at sunrise on July 2. Although both allegations were false, Longstreet failed to rebuke them publicly for three years. The delay damaged his reputation, and by 1875, the Lost Cause mythology had taken root.

Perhaps the most astonishing of these Longstreet attacks came from a very unexpected source: the widow of his friend George Pickett. Longstreet and Pickett had enjoyed a long, close association stretching all the way back to their service together in the Mexican-American War and their association to West Point. Longstreet served with distinction in the Mexican–American War alongside many of the men he would find himself fighting with (and against) at Gettysburg. In the Battle of Chapultepec on September 12, 1847, he was wounded in the thigh while charging up the hill with his regimental colors. As he fell, he handed the flag to his friend, Lt. George E. Pickett, who carried it on to the summit.

In the winter of 1862, during a scarlet fever epidemic in Richmond, Virginia, three of the four Longstreet children (Mary Anne, James and Augustus Baldwin) died within eight days. The blow was almost too much for Longstreet. An aide noted that his “grief was very deep,” while others commented on his change in personality. Because the Longstreets’ were too grief-stricken, it was General George Pickett (and his 16 year-old future bride LaSalle Corbell) who made the burial arrangements. Pickett shared Longstreet’s condemnation of Robert E. Lee’s actions at Gettysburg, openly stating “that old man (Lee) had my Division slaughtered.”

Pickett went on to a less-than-stellar financial career in the insurance business and never forgave Lee for destroying his division (and career). He lived the final years of his life quietly and modestly, farming and battling declining health. Pickett rarely spoke publicly about his war experiences and died on July 30, 1875, at the age of fifty. After Pickett’s death in 1875 Pickett’s third wife LaSalle began to write and lecture about her famous husband. While her general husband had spent his last years brooding about the disastrous charge that bore his name, his financially burdened widow decided to make the most of an opportunity.

In an attempt to revitalize his memory, she traveled around the country lecturing about her famous husband in an attempt to transform him into the hero of Gettysburg by way of the Lost Cause. Often, Pickett’s enhancement came at the cost of Longstreet’s reputation. It is ironic that Pickett should benefit at the expense of his friend and mentor, James Longstreet. Her tales of her husband’s life and times were highly romanticized and exaggerated, making it hard to separate fact from fiction.

LaSalle Corbell Pickett authored the celebratory history Pickett and His Men (1913), which historians claim was plagiarized, and two collections of wartime letters (1913, 1928), which historians claimed were fabricated. Nevertheless, her image of her husband at the moment his charge began — “gallant and graceful as a knight of chivalry riding to a tournament,” whose “long, dark, auburn-tinted hair floated backward in the wind like a soft veil as he went on down the slope of death” — has stuck in the American imagination. And her letters have been cited in works as diverse as Michael Shaara’s Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Killer Angels (1974) and Ken Burns’s documentary “The Civil War” (1990).

It would take a century of slow reassessment by Civil War historians to restore General James Longstreet’s reputation. Michael Shaara’s 1974 novel The Killer Angels, based largely on Longstreet’s memoirs and later made into the film “Gettysburg,” helped restore Longstreet’s reputation. Military historians now consider Longstreet among the war’s most gifted tactical commanders on either side of the Civil War. Part of that reassessment is due to a child bride, a gifted artist and one of Gettysburg National Battlefield’s newest monuments.

NEXT WEEK: Part 2 of General James Longstreet at Gettysburg

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest books are “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View,” “Irvington Haunts. The Tour Guide,” and “The Mystery of the H.H. Holmes Collection.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.