Located on the “point” of Washington Street and Kentucky Avenue, the Downtown Sheraton-Lincoln Hotel was the place to stay for anyone who was anyone visiting the Circle City during the tumultuous Sixties. The Sheraton-Lincoln’s Rail Splitter restaurant and Cole Porter ballroom hosted celebrities by the score and became the epicenter of Robert F. Kennedy’s 1968 Hoosier Presidential primary campaign victory.

The Hotel Lincoln was built in 1918 and designed by famed Indianapolis architects, Rubush and Hunter, the same firm that created the Madame C.J. Walker Theatre, Columbia Club and old City Hall, among others. The hotel, named after Abraham Lincoln, was the tallest flatiron building ever built in Indianapolis. It was acquired by Sheraton Hotels in 1955 and became known as the Sheraton-Lincoln Hotel. This four-corner intersection, obliterated in the early 1970s, was known as Lincoln Square in honor of Mr. Lincoln’s 1861 speech from the balcony of the Bates House across the street. A bust of Abraham Lincoln stood on a marble column in the lobby of the hotel for generations.

On Sunday November 12, 1961, Ray Charles checked in to the Downtown Sheraton-Lincoln Hotel. Ironically, his band spent the night in the Claypool Hotel across the street at Washington and Illinois Streets; the spot where Lincoln delivered his speech. That night, Ray got a call from a man whom he did not know. This man called with an offer to sell Ray drugs. Charles told him to come on over, and after which, the musician purchased weed and a dozen $3 capsules of heroin.

The next day, Ray and his band traveled to Anderson for a concert at the Wigwam, the new high school gym. After the show ended, they all headed back to Indianapolis. The bandmates got Ray to his room and left to see Aretha Franklin perform at the Pink Poodle at 252 North Capitol Ave. By all indications, Ray Charles stayed behind and got high.

The next morning, Tuesday November 14, 1961, at 9:00 a.m., Ray was awakened by a knock on the door. At first he ignored it but the knocking soon turned to pounding. Ray asked, “Who is it?” ”Western Union” was the reply. Still half asleep and dressed only in his underwear, Ray felt his way through the room and cautiously opened the door. Suddenly, two IPD detectives, William Owen and Robert Keithly, rushed in announcing that they had received an anonymous tip from a local drug dealer that there were illegal drugs in the room.

A search quickly found what they were looking for — Ray’s leather zippered “fix” bag. The detectives discovered 10 empty capsules, each containing heroin residue and a hypodermic needle. A closer search found a cold cream jar filled with marijuana they knew would be there. They charged Ray with a violation of the 1935 Indiana Narcotics act and for being a “common addict,” a charge designed more to humiliate Ray than to punish him. When the narcs pulled up Ray’s sleeves, they discovered what they described in court as “the worst track marks they’d ever seen.”

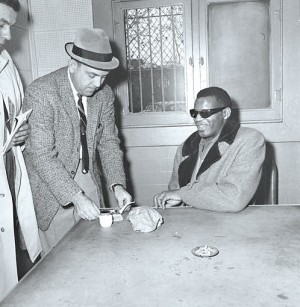

The officers led Ray out to the waiting police car and quickly took him to police headquarters a short distance away. There they fingerprinted and photographed their celebrity prisoner and brazenly let the press in to take pictures of the humiliated and confused musician. If you Google the pictures taken that day, you’ll see Ray at his lowest. Ray Charles, the greatest R & B musician of all time, broke down that day. Although blind, Ray knew instinctively what was going on. At first, he could only hear the familiar sound of one camera shutter clicking.

Then, as police let reporters in, he could hear the pop of flash bulbs snapping. He could feel the warmth of the flashes on his face followed by the clatter of the bulbs hitting the floor after being ejected. Ray must have felt like a man in a foxhole with bullets crashing all around. Ray’s soft sobbing soon broke into full-throated crying. The reporters yelled out questions at the helpless young man. “How did you get started on drugs, Ray?”

“I started using stuff when I was 16” Ray said as the tears rolled down from under the dark glasses hiding his eyes. “When I first started in show business. Then I had to have more and more.” Apparently ashamed by his statement and situation, he started to cry even heavier, saying “I don’t know what to do about my wife and kids. I’ve got a month’s work to do and I have to do it.” Then Ray stumbled back to the old excuses all junkies use; “I really need help. Nobody can lick this by themselves. I’ll go to Lexington (narcotics hospital). It might do me some good. I guess I’ve always wanted to go, but it was easier to go the other way. A guy who lives in the dark has to have something to keep him going. The grind is just too much.”

On drugs in the music industry, Ray said, “Believe me, there are a lot bigger guys than me who are hooked a lot worse.” Then Ray regained some of his old fire as he talked about the informant who turned him in, “Whoever he was, it was a dirty trick for him to pull.” Unbelievably, a reporter asked Ray if he’d like to see his kids using drugs. Ray began to cry again and said, “It’s a rotten business.”

Luckily the sideshow lasted only a few hours. Ray was released on $130 cash bond the next morning. As Ray left the jail, he covered his head with his overcoat from reporters. Ray left for a gig in Evansville that night, hoping to put the Indianapolis nightmare far behind him. Ray’s bandmates heard the news of Ray’s arrest on the radio that same morning. As they poured out into the hallways to talk about the situation, Ray came walking in. “Let’s get outta here, man” was all he said. They quickly packed their gear and started out on the 2 hour trip to Southern Indiana.

At the Evansville concert that night, reporters swarmed over Ray backstage just before the show. Frustrated, Ray jumped up and down with his fists clenched as if he were skipping rope. Sometimes he squatted so low that it seemed he would tip over backwards. Ray claimed it was the result of nerves and lack of sleep. He regained his composure and patiently answered the inevitable questions hurled at him by reporters. No, he had no idea how much money he’d spent on drugs in his lifetime, “That’s like asking how much you spend on cigarettes.” Ray claimed that he’d been misquoted and that he hadn’t been an addict since age 16, “It ain’t been that long, not near that long.” When asked what he planned to tell the judge the next morning back in Indianapolis, Ray said, “I’ll deny everything, you can quote me.”

News of the arrest spread fast, especially in the black press. As Ray arrived at Municipal Court for his scheduled appearance before Judge Ernie S. Burke, a huge mob of fans, reporters, television cameras and radio news crews were waiting for him. They jammed the halls of the courthouse, causing enough of a spectacle that Judge Burke threatened loudly to clear the courtroom and the building. Wisely, Judge Burke dropped the “common addict” charge and set Ray’s trial date on the drug possession charge for January 4, 1962, releasing Ray on $1,000 bond. As Ray left the courtroom, he told reporters, “I don’t feel up to answering questions about my life or this event,” then left Indiana for Nashville, Tennessee. The controversy followed Ray for the rest of the tour. Ed Sullivan immediately canceled an appearance by Ray on his popular TV show and several concert venues canceled Ray’s scheduled gigs. But it was nothing compared to the carnival atmosphere he’d experienced in Indianapolis.

Ray Charles would return to Indianapolis twice more in 1962 to clear up the drug bust. On January 9, 1962 Ray made his first appearance in court to answer the charges. He sat uncomfortably in a courtroom packed with media and fans, at times gently rocking back and forth with his head bowed and his hands tucked between his knees. Ray’s lawyer spent this session attacking the police for entering Ray’s room under false pretenses and with no warrant. Three weeks later, Ray returned for a 5 minute session as Judge Burke ruled the police search illegal and dismissed the charges. Even though Ray was a celebrity, he still had the same constitutional rights as every American citizen. Ray left the Hoosier courtroom for the last time with a general “No Comment” to the press. Ironically, at the time of his Indianapolis arrest, Ray’s single “Hit the Road Jack” was in the top ten of the Billboard charts. When he returned in January of 1962, Ray’s single “Unchain my Heart” was in Billboard’s top ten.

In 1964 he was arrested again for possession of marijuana and heroin. Following a self-imposed stay at St. Francis Hospital in Lynwood, California, where he kicked his drug habit in 96 hours (the total treatment took 3 to 4 months, though), Charles received five years probation. Charles reappeared in the charts in 1966 with a series of hits composed by the relatively unknown team of Ashford & Simpson. Ironically one of those hits was the song “Let’s Go Get Stoned,” which became his first number-one R&B hit in many years.

“Brother Ray” Charles pioneered the soul music genre by combining rhythm and blues and gospel styles like no one before or since. Frank Sinatra called Ray Charles “the only true genius in show business.” In 2002, Rolling Stone ranked Charles number ten on its list of the “100 Greatest Artists of All Time,” and second on their 2008 list of the “100 Greatest Singers of All Time” behind only Aretha Franklin and just ahead of Elvis Presley. On June 10, 2004, at the age of 73, Ray Charles died of complications resulting from acute liver disease at his home in Beverly Hills surrounded by family and friends.

Ray’s arrest became a footnote in the pop culture history of Indianapolis. But what became of the Downtown Sheraton-Lincoln Hotel? The hotel was demolished in April of 1973. It marked the first time that controlled dynamite was used to raze a building in Indiana. Public officials were reluctant to allow dynamite rather than the traditional wrecking ball, but the promise of saving both time and money tipped the scales. The exact time was kept a secret and the surrounding area was cordoned off for blocks. Over 200 spectators gathered to witness the building fall to the ground. Today, the Hyatt Regency stands where the Sheraton-Lincoln once was.

The Hyatt was built with a triangular shape to pay homage to the angling street and flatiron building that once stood on the site. The building opened in 1977 and it’s circular upper floor houses the Eagle’s Nest, a rotating restaurant. One of the most prominent features of the Eagle’s Nest is a piano bar. On the weekends, guests are entertained with songs from the American songbook. No doubt, Ray Charles tunes are among them. It just goes to show you, what goes around, comes around.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest books are “Bumps in the Night: Stories from the Weekly View.”, “Irvington Haunts: The Tour Guide” and “The Mystery of the H.H. Holmes Collection.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.