This column originally appeared in March, 2013. Al is out researching his next column.

Last week, we left Greenfield a century ago; March 25th, 1913, underwater. The “Black Night of Terror,” the “March Flood,” or the “Great Flood of 1913″ had come and gone through the Hancock County seat, leaving devastation in its wake. And it was headed straight for Indianapolis. On Tuesday the National Weather Bureau sent out the following warning: “Below Indianapolis the river will rise rapidly and the public should prepare for higher stages than have been experienced for many years. Every precaution should be taken by those living along the lower course of he river, as the rise will be unusually rapid and will reach a point several feet above the danger line.” Late that Tuesday morning, the first levee failed, flooding Indianapolis via the White River and Eagle Creek.

Fortunately, most Hoosiers heeded the warnings, gathered their families, belongings and pets and fled to higher ground, saving countless lives. Witnesses on the west side of Indianapolis claimed they saw a wall of water more than two stories high when the White River levee burst at Morris Street. Indianapolis’ tranquil Eagle Creek, normally 64-feet-wide at best, spread to an angry class five rapid half a mile wide. Astonished bystanders watched as the White River tore through its levees at many points. Around noon on Tuesday, Fall Creek jumped its banks, flooding a large part of the city’s north side residential district, ending streetcar service and putting the water works and other public utilities out of commission. Many families living in homes in the danger zones packed valuables into wagons and carried furniture up to the second floors and attics of their homes.

By 3 p.m. the muddy water was beginning to trickle down the levee. Whenever a leak appeared, a brace of men rushed over to plug it using bags of sand and bales of straw jammed in place by telephone poles. Around 4 p.m., as the men were busy shoring up the levee north of the Morris Street bridge, water unexpectedly broke through the sandbags piled on the other end of the bridge at the western corner of Morris and Drover streets. The break was not a massive wall of water as some claimed, but rather a steady flow as if a massive spigot had been opened allowing thousands of gallons of water to pour through the breach while gradually enlarging the opening as each frantic moment trickled past. Now, people abandoned their wagons and tied what valuables and food they could gather into bundles, grabbed their children, and began to flee across the Morris Street Bridge. The evacuation proceeded in agonizing slow motion; the water first rising past their ankles, then up to their knees, finally settling around their waists.

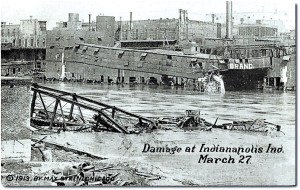

Still, the White River kept rising. By 6 p.m. the river burst through the base of the levee about four hundred feet upriver of the bridge. By early evening, Indianapolis was flooded east of Harding Street, in some places the water crested as high as 15 feet. By Wednesday, the Washington Street Bridge was destroyed, cutting the main artery between the Circle City and all points west and taking the railroad tracks with it. The recently created suburb of West Indianapolis and valley of West New York Street were the hardest hit areas; a region principally populated by railroad and stockyard workers. Created as one of the city’s first suburbs, the southwest annex was roughly bounded by the White River to the east, the Pennylvania Railroad line to the north, Eagle Creek to the west, and Raymond Street to the south. The residents never knew what hit them.

The first floor of the newly opened St. Vincent’s hospital at Fall Creek and Illinois flooded and Sister Mary Joseph and her staff moved their patients to the second and third floors for safety. Articles titled “$500,000 Loss at Peru,” “Over the Muncie Levee,” “Boats in Carmel Streets,” “Danville Cars Stopped,” “Bloomington is Cut Off, ” and “Shelbyville Levee Breaks” appeared on a single page of The Indianapolis News Wednesday edition. The flood crested in Indianapolis on the morning of Thursday, March 26th. As the water receded, the damage was unveiled and the residents were left to comb over the debris of the worst flood the state ever saw. A six-square mile area was destroyed, displacing 4,000 Hoosier families. Because of the early warning, the loss of life was tallied at five known fatalities; however, witness stories swear that total had to be much higher.

It was Easter week and Indianapolis was not alone in their soggy sorrow. Levees burst all around the state — on the Mississinewa River in Marion, on the White River in Muncie, on the Wabash River in Lafayette, and on the Ohio River in Lawrenceburg — flooding the cities they were supposed to protect. In the southern part of Kokomo, Wildcat Creek flooded over its levee to saturate city streets with eight feet of water. Thousands of telephone and telegraph poles and wires were downed by the flood, making an orgnaized relief effort nearly impossible. To obtain the necessary food, shelter, and medical supplies for the injured and suddenly homeless, Governor Sam Ralston appealed for help to cities around Indiana as well as to other states. Donations of money, blankets, food, and even coffins poured in just as quickly as the water poured out.

Indianapolis was not only the geographical center of the Midwest’s monumental winter storm system in March of 1913, with a population of 235,000, it was also the single largest city affected by the natural calamity. So what kind of storm caused the Great Flood of 1913? It began like any other normal Midwestern winter storm, but soon developed special characteristics conducive to flooding. A strong Canadian high with its accompanying windstorm stalled off Bermuda, thus halting the normal eastward travel of its trailing low bringing all the rain. Then another Canadian high moved in from the west, squeezing the low into a long, low-pressure trough between the two highs, its center stretching diagonally from southern Illinois, across southern and middle Indiana, and across northern Ohio. Up that diagonal path, at least two lows moved in fast succession, the rain of one merging together into the next. But nothing in the weather observations or theories of the day prepared the U.S. Weather Service, or any other body, for the unprecedented volume of water that fell out of the sky during those four days of March 1913.

Regardless of how the flood waters had arrived, and receded, perhaps the true horror of the Great Flood of 1913 was the aftermath. The flood waters were now stagnant pools of sick water filled with raw sewage, rotting food, dead pets and livestock, bugs, snakes, and disease carrying rodents. Day after day, Hoosiers were bombarded with newspaper headlines warning of looting and arrests, waterborne disease wielding parasites, guards posted to keep away opportunistic invaders, health agencies warning of the dangers to unsuspecting children and dangerous symptoms caused by clogged drains. For a time, the city was under siege. Luckily, the flood brought about changes in national weather forcasting by identifying the presence of stalled lows as the major factor in localized flooding, local government with the passage of stricter code enforcement in response to the flood’s aftermath, and the resurgence of the Red Cross as a National relief agency. Statewide, more than 90 people drowned and at least 180 bridges were destroyed when up to 11 inches of rain fell across the state in a five-day period. Could it happen again? Sure, but until that day, the Great Flood of 1913 remains our state’s worst ever.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest book is “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook