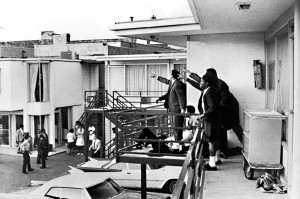

On Thursday, April 4, 1968, Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. was staying in room 306 at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. Dr. King traveled to the river city in support of striking African-American city sanitation workers. King had gone out onto the balcony and was standing near his room when he was struck at 6:01 p.m. by a single .30-06 bullet fired from a Remington Model 760 rifle. The bullet entered King’s right cheek, breaking his jaw and several vertebrae as it traveled down his spinal cord, severing his jugular vein and major arteries in the process, before lodging in his shoulder. The force of the shot ripped off King’s necktie. King fell violently backward onto the balcony, unconscious as his life ebbed away. Despite his faint pulse, he died shortly afterwards at Saint Joseph Hospital. He was pronounced dead at 7:05 p.m. In an instant, the Lorraine became one of the most famous motels in the United States, but for all the wrong reasons.

The Lorraine Motel was owned by Walter Bailey who renamed it to honor his wife Loree. For over two decades the motel, located at 450 Mulberry Street on the south edge of downtown Memphis, was THE place to stay for visiting minority musicians, athletes, clergymen and travelers passing through the segregated Jim Crow South. Walter and Loree Bailey were hands on owners who did everything from taking reservations to cooking dinners in the attached restaurant. When that rifle shot rang out, Loree Bailey suffered a stroke on the spot. Loree was at her post as the motel’s switchboard operator when she suffered her heart attack. When Rev. Samuel Kyles attempted to call an ambulance using the phone in the motel room, nobody was at the switchboard to direct the call. Loree Bailey died five days later on April 9th, the same day as Dr. King’s funeral. The official cause of her death was listed as a brain hemorrhage.

Walter Bailey continued to run the motel, but he never rented Room 306 and the adjoining room 307 again. He turned them into a memorial to Dr. King. The room was preserved exactly as it looked on that tragic night. There are two beds: one was King’s and the other was occupied by Dr. Ralph Abernathy. King’s bed was not fully made because he was not feeling well and had been lying down. Dishes were left in the room from the kitchen where Loree Bailey prepared food (fried Mississippi River catfish) for the motel room’s guests. In time, Bailey converted the other motel rooms to single room occupancy for low-income residential use.

After King’s murder, the Lorraine Motel began a long and steep decline. Despite Bailey’s efforts to preserve it as a working historical landmark, people no longer wanted to stay there. Walter Bailey continued to run the motel as a shadow of its former self. Bailey stood by helplessly as his once high-end establishment became a brothel and haven for drug dealers. He declared bankruptcy in 1982 and closed the motel. It was scheduled to be sold at auction but a “Save the Lorraine” group, part of the Martin Luther King Memorial Foundation, bought it at the last minute for $144,000 in December 1982 with the intent to turn it into a museum. Walter Bailey died on July 7, 1988 at the age of 73 and did not live to see his motel turned into a museum.

The Lorraine’s last tenant was Jacqueline Smith, a live-in housekeeper and front desk clerk at the motel since 1973. When told the Lorraine had been sold, she barricaded herself in her room and refused to leave. She was forcibly removed by law enforcement officers just four months before Walter Bailey died. Ms. Smith was lifted, lawn chair and all, and gently placed on the sidewalk across the street from the motel. Construction workers then moved her belongings into the street. With that, The Lorraine Motel officially closed for good on March 2, 1988.

In 1991 the National Civil Rights Museum opened to the public and Walter and Loree Bailey’s dream was finally realized. The Lorraine is now filled with artifacts, films, oral histories, and interactive media, all designed to guide visitors through five centuries of black history.

Despite being dragged from her room, Jacqueline Smith never really left the property. She set up camp on a street corner opposite the Lorraine, where she has waged a one-woman campaign protesting the institution’s existence for nearly 30 years. There she stays, 21 hours a day, calling for a boycott of the Civil Rights Museum. She leaves only to find food and go to the bathroom, all her worldly possessions stored under a blue tarp nearby.

Jacqueline believed the Lorraine should be used for helping the poor and needy, rather than a celebration of Dr. King’s death. She told visitors that “Memphis has always been a city where the two biggest attractions are memorials to two dead men: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Elvis Presley.” Near Smith’s perch was a sign that read, “Stop worshiping the dead.” Smith argued that Dr. King’s legacy would have been better honored by converting the motel into low-income housing or a facility for the poor. “It’s a tourist trap, first and foremost… this sacred ground is being exploited.” Smith said of the museum that she never set foot in, despite invitations from the museum staff to do so. Smith’s call for a boycott has gone largely unheeded and she maintains her vigil outside the Lorraine to this day.

Although the inside, except for room 306, has changed drastically, the Lorraine Motel exterior remains instantly recognizable; forever frozen in the spring of 1968. Two classic cars — a white 1959 Dodge Royal with lime green tail fins and a white 1968 Cadillac — are parked in front of the motel under that fateful balcony. The Lorraine motel sign still maintains silent witness. A large wreath hangs on the balcony outside Room 306, to mark the spot that changed the world. Flashes of those iconic photographs of King’s associates desperately pointing off into the distance at an assassin who is no longer there dominate the visitor’s mind. The eyes trace an imagined path to the window a football field away from which the death shot was fired. The scene is indelibly burned into America’s collective memory

Room 306 remains faultlessly preserved. The unmade twin beds, half-filled ashtrays, black rotary phone, television with rabbit-ears antenna can all be viewed through a Plexiglass window. The meticulous attention to detail, which I was fortunate enough to witness myself when I visited with my wife and children on the 33rd anniversary of the sad event in 1991, is due and owing to one man who became an unexpected documentarian of an American tragedy.

Within hours of the assassination, Life magazine photographer Henry Groskinsky was on that balcony and through the door of King’s room. Although the physical body of Martin Luther King Jr. was gone, ethereal traces of the man remained. Groskinsky captured them all: a wrinkled shirt, a Soul Force magazine, a Styrofoam cup half full of coffee; a sign that King had momentarily left the room and would return soon. King’s still unpacked suitcase with a can of shaving cream, pajamas, brush and his book, “Strength to Love” lay undisturbed.

The TV was still on when Groskinsky arrived, King’s face now occupying every newscast and eerily appearing in the background of many of his photographs. That wall upon which the TV had been mounted is now gone and has been replaced with a sheet of clear plastic through which millions of children have pressed their faces against, straining to see this holy spot. Curious eyes dart back and forth at the relics in the room: the rumpled coverlet on King’s double bed folded back, a can of pomade on the vanity, a Gideon Bible on the nightstand, a newspaper with the headline “Racial Peace Sought by Two Negro Pastors,” and just outside the window, the balcony where King collapsed, a square of its original concrete flooring preserved denoting where the great man’s life trickled away.

It was the photo of the briefcase that resonated with me as an image of the suddenness of it all. Martin Luther King, Jr. has become a myth, a legend, a saint to most Americans. But the photo of his everyday possessions stands as testament to the fact that he was also a husband, a father and a man. However, the images captured by Groskinsky which haunt my dreams to this day are those of the aftermath of the assassination in its barest form.

One need only visit the Web and Google Henry Groskinsky’s name and a quick search will reveal two more photos from the fateful night. They are graphic and shocking in nature, so be warned. Both captioned “Clean Up,” one pictures Walter Bailey’s brother Theatrice as he scoops up King’s blood from the ground and places it into a jar. The other is less graphic but equally poignant and pictures Theatrice as he attempted to clean up Dr. King’s blood from the balcony with a broom. If these photos of the aftermath at the Lorraine Motel didn’t exist, the scene could not be believed.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest books are “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View.” and “Irvington Haunts. The Tour Guide.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.