This past fall, I drove to a place called White’s Farm in Brookville, Indiana, not far from Cincinnati. Every Wednesday you’ll find over 100 flea market and antique dealers set up in the hills and dales of an area once riddled with the remnants of Ancient Native American Indian burial mounds. Brookville is one of those shows that starts “flashlight early” with most dealers arriving around 3 a.m. and packed up and gone by 10 a.m. It was one of those fall “dew you can chew” mornings, when the air is so think you can practically catch droplets on your tongue like snowflakes.

While walking up a hillside my flashlight caught hold of a pile of old paper and photographs and I instinctively froze. After all, I’m a paper and photo guy and damp cool mornings are the bane of my flea market existence. Even from 15 feet away, I recognized a familiar face smiling out from the crowd. It was a hero from my past. It was Bill “Bojangles” Robinson.

If you’re old enough to remember black and white TV, the original Sammy Terry TV show, Timothy Church-mouse or Cowboy Bob and Janie, then you should remember Bill Robinson. There was a time when television stations actually went off the air at night and didn’t come back on until farm shows or cartoons popped up the next morning. Back then, it was a badge of honor to say you made it up to watch the flag wave to the rhythm of the National Anthem.

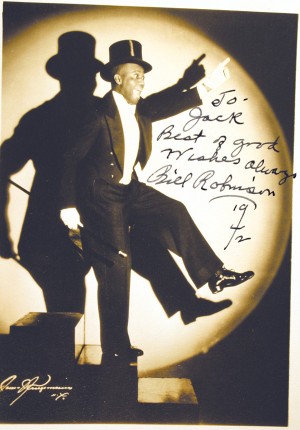

After the weekend cartoon shows were over and before the sports programming began, well, that was the time for America’s sweetheart: Shirley Temple. And right there next to that darling little dancer, matching her step-for-step, was Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. And here, right here in the soggy farm fields of Brookville, Indiana, was a 5×7 World War II Era photo autographed by Bojangles himself! I sheepishly asked the vendor what the story was on the group of photographs and he replied, “Oh those all belonged to a famous Big Band leader from Cincinnati and those are all gangsters from Newport (Kentucky).”

I held up the Robinson photo in particular and the seller stated, “Oh he (the band leader) was great friends with Bill Robinson.” I asked the dealer what he wanted for the photo and he said he was trying to sell the whole collection as one lot. He then added, “I have a whole suitcase of this stuff in my truck.” Oh really? Of course I asked to see the suitcase and sure enough, it was crammed full of wonderful things. I negotiated a price — more than I expected to pay, but less than the value of my childhood memories. In instances like this, you lead with your heart, dig for your wallet and hope your wife will understand.

For the sake of full disclosure, I must admit that I once owned a photo signed by Bill Robinson. Bojangles signed it for an Indiana Mayor whose name now escapes me. I sold it to a collector in the late 1980s for $100. But I rationalized the sale of the relic because the photo literally looked like it had been dipped in water and $100 might as well have been $1,000 to me and my young bride. By finding this photo on a dew soaked Southern Indian hillside, I felt the pendulum had swung back my way.

I took the suitcase home and eagerly, but carefully, began to disassemble the contents. As my fellow collectors will attest, it doesn’t get much better than this. Suitcases full of unpicked goodies fill the slumber-time dreams of every collector, regardless of the subject one desires to collect. This suitcase did not disappoint.

Turns out that this grouping represented the personal memorabilia of 1930-40s Era Queen City Big Band Leader, musician and composer “Deke” Moffitt (1906-1976). During his career, Moffitt performed with Red Skelton, Bill (Bojangles) Robinson, Perry Como, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Martha Raye, Betty Grable and the Three Stooges. After his touring career was over, Deke became music director for a Cincinnati theatre and later a high school music teacher.

Among the collection were contracts, sheet music and records of songs Deke had composed and letters/correspondence from Deke’s years on the road, many from famous musicians. There was even a photo of Deke clowning around outside of what looked like a theatre backstage door with the Three Stooges (Larry, Moe & Shemp). But what caught my interest were the few items from Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Along with the photo I mentioned previously, there was a handwritten note to Deke and a telegram from Bill. I’ll tell you what else was in there later on.

First, I want to try and explain why Bill “Bojangles” Robinson matters to me and more importantly, why he should matter to you. The predominate reason for my admiration is simple: I can’t dance. For the same reason I guffaw at the Three Stooges, giggle at Groucho Marx and crack up at the Little Rascals, I can’t help but stop and gaze in wonder whenever I see the masters dance. Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, Gregory Hines, John Travolta: they all stand on the shoulders of Bill Robinson. Except none of the above were burdened with the constraints of Jim Crow America.

Friends say there were three certainties about Bill Robinson: he loved to eat vanilla ice cream, gamble with dice or cards, and dancing was his life. At the time of his divorce his wife Fannie accused him of being a danceaholic — a man willing to sacrifice everything to dance. While his personal life was full of contradictions, his peers and historians agree he was one of the greatest American dancers of all time.

Bill “Bojangles” Robinson was born Luther Robinson in Richmond, Virginia, on May 25, 1878. He claimed he did not like the name Luther, so he traded names with his younger brother Bill. Apparently his little brother didn’t like the name either so he changed his name to “Percy” and later became famous on his own as a dancer and musician. Although orphaned and reared by a grandmother who had been a slave, Bill Robinson would become the best known and highest paid African-American entertainer in the first half of the 20th century. Robinson began hoofing in beer gardens at age 6 and quit school the next year to begin work as a professional dancer. His career started in minstrel shows, then moved to vaudeville, Broadway, the recording industry, Hollywood movies, radio, and television. He died 65 years ago this week on November 25, 1949.

The name “Bojangles” mirrors it’s enigmatic namesake. Some say the name referred to his happy-go-lucky ebullience while others claim the name refers to Bill’s fiery, argumentative disposition. Today, the word Bojangles refers to a style of percussive, rhythmic tap dance originated by African-Americans. The word is southern in origin and means “mischief maker.” The nickname was appropriate for Robinson, whose popularity transcended his race, despite a personal life chronicled by newspapers and magazines as a series of misadventures and court appearances.

While Robinson didn’t invent tap dancing, he was the artist chiefly responsible for getting tap dance “up on its toes” by dancing upright and swinging. Before Robinson tap was most often a stoop-shouldered, flat-footed shuffle style, sometimes known as “sand dancing.” Robinson performed on the balls of his feet with a shuffle-tap style that allowed more improvisation. This new style got him noticed and eventually made him a legend. Bojangles’ unique sound came from using wooden taps and his direct claim to fame would be the creation of his famous “stair dance,” which involved tapping up and down a flight of stairs both backwards and forwards — a style he unsuccessfully attempted to patent.

Following the demise of vaudeville, Broadway beckoned with “Blackbirds of 1928,” an all-black revue that would prominently feature Bill and other black musical talents. Soon, he was headlining with Cab Calloway at the famous Cotton Club in Harlem. Robinson is also credited with having introduced a new word, copacetic, into popular culture, via his repeated use of it in vaudeville and radio appearances. Robinson was a true pioneer in his field with many “firsts” to his credit.

A popular figure in both the black and white entertainment worlds of his era, he is best remembered today for his dancing with Shirley Temple in a series of films during the 1930s. Although a trailblazer and acknowledged pioneer, Robinson battled inner demons that belied his demeanor as a happy and easygoing character on the big screen. On one hand, he had to deal with discrimination and racial injustice by whites and on the other hand, he was labeled as the quintessential “Uncle Tom” by his own people. Decades of dealing with this untenable double standard turned Bojangles into a split personality capable of unwavering loyalty and kindness to some while turning him into an angry man, frustrated by his second-class treatment in society who was known to flash a gun to others. Measured by today’s standards and celebrity shenanigans, Robinson’s behavior would be considered tame.

Next week, I’ll continue the story of this man and tell you what else I found in that suitcase.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest book is “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.