This story originally ran in 2009.

As I write this, news reports run on the television all day long marking the anniversary of demented Reverend Jim Jones’ massacre of 900 members of the People’s Temple church in Jonestown, Guyana, which followed the murder of 9 people (including one U.S. Congressman) at the Jonestown air strip in Guyana just hours before. Most people who think of this demented messiah figure Jones equate him with the San Francisco area and the remote jungles on the northern edge of South America. Sadly, the truth is that Jones was a Hoosier who started his sojourn not far from the Indianapolis east side.

His story, before the lunacy began, is not unlike that of any other typical Indiana kid. He graduated mid-term with honors from Richmond High School in 1949. He was married to his high school sweetheart, Marceline Baldwin, in June of the same year. Jones attended Indiana University and graduated from Butler University. However, the seeds of Jones’ dementia can be found in the roots that he set down here in Indiana and her capitol city — a period of his life not many historians have chosen to focus on as an explanation of his psychosis.

James Warren Jones was born an only child on May 13, 1931 during the Great Depression in a rural Indiana town called Crete, located near the Ohio state line. When he was three, his family moved to the nearby town of Lynn. His father, James Thurman Jones, was a veteran of World War I who had been disabled by a mustard gas attack. His absentee dad, embittered by the Depression and his inability to find work, joined the Ku Klux Klan. Records indicate that the elder Jones spent five years in a mental hospital in the 1920s. On the other hand, Jones’s mother, Lynetta Putnam, was a well-liked, hard-working woman who kept the family together. Jones would claim that his mother was part Cherokee Indian, but there is little evidence to support the claim. His parents divorced in 1945. Jim chose to live with his mother in Richmond, Indiana.

His parents raised Jim as a strict Baptist, and apparently, Jones was introduced to the Pentecostal Church by a neighbor, Myrtle Kennedy. She regularly took Jim to Sunday School and gave him instruction in the Bible. While not yet a teenager, Jones began his theological quest by attending the services of several eastern Indiana churches. This introduction, combined with the racial segregation of eastern Indiana community, appears to be the beginning of Jones’ utopian theology of “Social Justice.” It didn’t take long for Jones to settle at the Gospel Tabernacle Church on the edge of town. The members of this Pentecostal church were often derisively referred to as “Holy Rollers” for their belief in faith-healing, snake handling and speaking in tongues.

The pre-teen phenom soon found himself in the pulpit, dressed in a plain white sheet, gesticulating wildly and thumping the Bible. Jimmy Jones loved the attention.

In 1947, at the age of 15, Jones began preaching on the sidewalks of Lynn, but no one seemed interested. So he walked 16 miles from his home in an area on the wrong side of the tracks near Richmond to preach his message. Jim seemed to instinctively pick a working-class black neighborhood in which to begin his ministry — a pattern that would be repeated time and time again in the years to come. Jones himself would describe his religious transformation: “In Pentecostal tradition, I saw that where the early believers stay together they sold all their possessions and had all things in common.”

Jim attended Indiana University for three semesters before moving to Indianapolis in the summer of 1951 to study law as an undergraduate at Butler University. (Jim would attend night school at Butler and earn his degree in secondary education in 1961.) The Joneses settled in a small apartment behind the Shriner’s Temple in Indianapolis. Jim’s wife Marceline paid the bills working as a nurse. It was at about this same time that Jones gave up the study of law and decided to focus full-time on his dream of becoming a minister. By 1952, Jim was a student pastor at the Somerset Southside Methodist Church in Indianapolis. He would leave the Somerset church because it openly practiced segregation and did not allow minorities in it’s congregation. In 1953, Rev. James W. “Jim” Jones became an associate pastor at the Laurel Street Tabernacle (Assemblies of God) in Indianapolis at Prospect and Laurel Streets near Fountain Square.

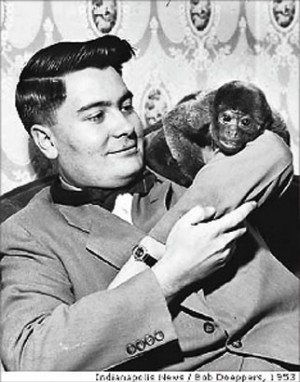

By 1954, Jones had established the first “Community Unity” Church on North Delaware street in Indianapolis, while also maintaining his position at the Laurel Tabernacle. This is where Jones’ story takes on one of the strangest aspects as anything I’ve ever seen in researching biographies. To raise money for his new church, Jim Jones began selling monkeys door-to-door. Yes, real living, breathing wild Spider Monkeys to the citizens of Indianapolis for $29 each. He had at least moderate success and it’s possible to see the ads for Jim Jones’ monkey business (pardon the pun) in back issues of the Indianapolis Star. The monkey-selling venture was successful enough to allow Jones to establish a new Community Unity Church located at Hoyt and Randolph Streets on West 10th St. about a mile and a half from the infamous Central State Mental Hospital.

Next Week: Part 2 of the Jim Jones story.

Al Hunter is the author of the “Haunted Indianapolis” and co-author of the “Haunted Irvington” and “Indiana National Road” book series. His newest books are “Bumps in the Night. Stories from the Weekly View,” “Irvington Haunts. The Tour Guide,” and “The Mystery of the H.H. Holmes Collection.” Contact Al directly at Huntvault@aol.com or become a friend on Facebook.